Despite its diminutive size, Britain is the birthplace of an extraordinary number of adventure sports and outdoor pursuits – from sport climbing and fell running to pilot gig rowing, coasteering, ghyll scrambling and cave diving – many of which have subsequently become popular around the planet in various forms, but which were initially inspired and shaped by the unique terrain found in the craggy and curious corners of the UK.

The best outdoor activities for adults in the UK

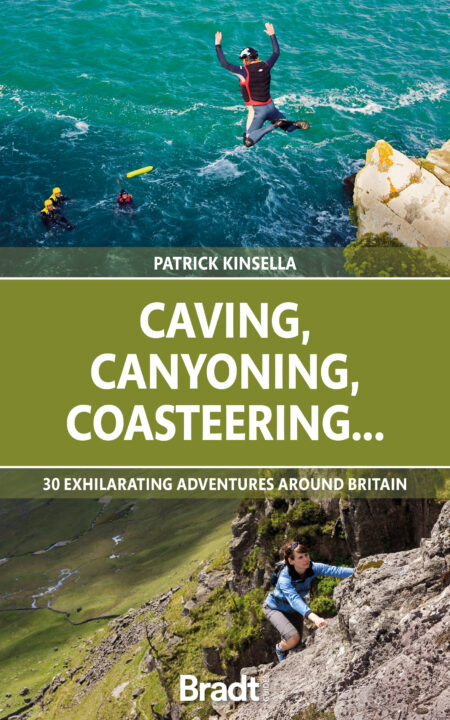

The idea behind Caving, Canyoning and Coasteering is mainly to explore the origin stories of these activities and their continued appeal. As the book’s title indicates, you will find chapters about caving, canyoning and coasteering experiences, but the best outdoor activities are far from limited to these three sports. Also included are adventures involving scrambling, ambling, running, climbing, pedalling, paddling, diving, swimming, skating, surfing and sailing. Whether you’re an experienced outdoor adventurer looking for a new angle on an activity you know, or a complete beginner, there are unique experiences for you to enjoy.

The common denominator is that all the pursuits are either entirely human-powered, or involve people harnessing the natural elements. Beyond a brief guest appearance by an e-bike in the chapter about bikepacking, no motorised vehicles have been used. Whichever activity, sport or pursuit you choose, it’s a great way to explore the often-unseen elements and quieter corners of Britain.

What SUP? Stand-up Paddleboarding

Stand-up paddleboarding, or SUP as it’s invariably abbreviated to, has been one of the fastest-growing adventure pursuits to arrive on the outdoor scene for decades. If you visit any stretch of coastline around the UK – or anywhere else – on a calm summer’s day, there will be a fleet of SUPs out on the water. Take a stroll along a riverbank or canal towpath on a half-decent morning, or wander around a lakeshore where paddling is permitted, and again, you’ll almost certainly see paddleboarders.

One of the wonderful things about the activity is that – unlike many outdoor pursuits – it’s not dominated by any particular narrow demographic. You see just as many women out on boards as men, and the age range is super diverse, from proper youngsters to silver-haired SUPers. Exact numbers are hard to come by, but it’s pretty obvious stand-up paddleboarding has overtaken sea kayaking, canoeing and whitewater paddling in terms of popularity and participation.

Andy Gratwick, the Head Coach of the British Stand Up Paddle Association (BSUPA), tells me they have 105 recognised schools nationwide in Britain, and he estimates that around 30,000 paddlers get a structured lesson through their schools network each year. ‘And we are by no means the whole market,’ he adds. ‘So maybe triple this number.’

Although prices have gone down as more budget-orientated brands have jumped into the market to surf the success of the sport, a SUP set-up still isn’t particularly cheap – for a reasonable quality board, paddle, PFD, pump and the various paraphernalia that goes with it, you’d be lucky to get much change from £500, and the better brands (which make longer-lasting, more performance-orientated boards and paddles) are much more expensive. And that’s before you’ve invested in a wetsuit, without which SUPing beyond the summer months can be pretty uncomfortable.

Neither is SUPing particularly beginner friendly – at least, not without some tuition. It’s one thing kneeling on a board and doing loops on a sunny day when the water is like a millpond, but to perfect your paddling style properly takes plenty of practice, and only then can you stand up and go in a straight line without constantly changing hands, let alone venture out in less benign conditions, or explore more exciting waterways.

Where to try it

You can SUP all around the United Kingdom coastline, but be very mindful of weather conditions and tides when on the open sea. Protected bays and coves are best for beginners. Canals can generally be paddled at any time, but sadly SUPing (along with kayaking and canoeing) is heavily restricted on the rivers of England and Wales – in Scotland outdoor access is much better, and you can paddle most rivers and lochs. Besides the Norfolk Broads, another wonderful waterscape to explore on a board in England is the Lake District, and in Wales Bala Lake/Llyn Tegid is an excellent spot, where you can typically enjoy calm conditions.

By Gorge! Canyoning and Gorge Scrambling

Water is very good at finding the fastest and most exciting route down any given mountain, hillside, cliff or crag, and following high-flowing streams as they plunge over drops and rush through narrow gaps has spawned an especially exciting adventure sport.

At entry level – where anchored ropes, technical downclimbs and abseils are not required to shoot the route – the pursuit can be referred to as gorge scrambling. Canyoning always involves descending routes, using ropes and other equipment, while gorge scrambling can be done in either direction. The activity involves starting at the top of a water-carved ravine and following the flow, leaping from ledges into plunge pools, swimming across stretches of water, downclimbing crags, sliding and scrambling over rocks, and abseiling beside (and sometimes within) waterfalls as you go.

Canyoning could be described as a hybrid sport, using a mixture of skills employed in other outdoor pursuits. You can envisage it as gravity-assisted wild swimming, or white water kayaking without the boat, or perhaps semi-aquatic scrambling, with some rock climbing and rappelling thrown in for good measure.

But really it has evolved into a very distinct activity in its own right, with defined grading systems and a set of self-imposed rules to protect both the participants’ safety and the environment it takes place in. A culture and community has grown around it, with governing bodies set up to encourage good practice and promote the sharing of information about canyoning routes, and specific equipment developed to make the experience safer and more enjoyable. On all levels, the activity is challenging, thrilling, occasionally chilling, and delivers a unique experience every time you head out.

Where to try it

I explored the canyons, gorges and waterways of the Brecon Beacons, now officially named Bannau Brycheiniog, and the Lake District. Besides Wales’ Waterfall Country and the Lakes, there are excellent gorge scrambling and canyoning routes in Snowdonia, Yorkshire, Devon and elsewhere. See the map at the Canyon Log website for more.

Think bike… bikepacking

As a lifelong cyclist who loves larking around on trails, exploring new places and sleeping outside, I should have been bikepacking for decades, but the whole concept is a relatively new one. More accurately, it’s a fresh take on a long-enjoyed activity.

People have been bike touring for donkey’s years, using panniers to carry camping gear while cycling around country roads, often venturing far and wide, around regions, countries and even continents. Bikepacking – a term popularised in the 2000s – takes the concept of cycle touring off-road and on to trails, with the steed of choice typically being a mountain bike or, more recently still, a gravel bike. Instead of relying on a couple of large panniers, gear is usually stashed in smaller purpose-made packs attached to various parts of the frame, so you can pedal right out into the wilds, tackling rough, tough and technical trails, and exploring remote corners of the outdoors.

The concept of bikepacking is pretty self-explanatory: it’s exactly like backpacking, but instead of carting your tent, sleeping bag and other overnight equipment on your back, you attach it to your bike. In practice, there’s more to get your head around, because packing a bike properly is nowhere near as simple as stuffing gear into a rucksack. The dynamics are similar – you need to distribute the weight sensibly and evenly, so your centre of gravity remains as low as possible, and you’re not lopsided – but with a backpack you can usually achieve this by simply putting the heavy stuff at the bottom, whereas with bikepacking, there’s more to think about.

You can enjoy bikepacking on a mountain bike or a gravel bike. The latter has drop handlebars (like a racing bike) and a rigid hard-wearing frame, with disc brakes on the wheels and chunky off-road tyres. You will need lightweight minimalist camping kit (a tent or tarp, sleeping bag and mat, stove, etc). There are now myriad bags available specifically designed for bikepacking, from brands like Alpkit, Chrome and Fjällräven.

Where to try it

Dartmoor’s gateway towns are Okehampton (north), Ivybridge (south), Bovey Tracey (east) and Tavistock (west). Okehampton and Ivybridge have train stations. The trailheads for the rideable section of the Ridgeway are found in Goring on-Thames, Oxfordshire (closest train station Goring & Streatley) and Avebury (closest railway station Pewsey). The Peak District trails are easily accessed from Sheffield, which is well serviced by trains. To reach Swaledale and the Dales Bike Centre, take the M1/A1, turning west at Catterick. The Leeds-Settle-Carlisle railway line is one of Britain’s most scenic, crossing the Yorkshire Dales and stopping at stations including Horton in Ribblesdale, Ribblehead, Dent (England’s highest main-line station), Garsdale and Kirkby Stephen.

There are also several iconic bikepacking events and challenges in the UK, including the enormous Pan Celtic Race, a self-supported, ultra-endurance challenge that sends riders through Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, the Isle of Man and Brittany, which takes a different route each year. There are, of course, many far more accessible gravel-riding and bikepacking events, such as the two-day

Dunoon Dirt Dash in Scotland and the Dorset Dirt Dash in southwest England.

Snowholing and winter Munro bagging

When imagining a shelter made from ice and snow, many people – myself very much included – will immediately call to mind an igloo. But, when you’re actually out there, surrounded by snow, which typically gets blown around and banked up in deep drifts, it makes an awful lot more sense to dig out a den, burrowing into the building material, rather than spending time making bricks and embarking on a complicated construction project. Snowholing, as this activity is called, enables outdoor adventurers to spend relatively comfortable midwinter nights, sleeping among the elements in super-remote places, without having to cart heavy four-season tents around.

Snowholes vary enormously in size and sophistication, from crude caves quickly carved by climbers and mountaineers benighted on slopes, to relatively luxurious temporary abodes built by hill hikers, snowshoers and ski tourers out exploring the wild white expanse, who have come equipped with all the right gear and spent several hours constructing their ice house. In midwinter, when sunlight only graces the Scottish Highlands for eight hours a day (if you’re lucky), having the ability stay out overnight enables you to take on longer escapades without resorting to night walking. And who isn’t excited at spending the night in a snow cave?

But this is not something to be taken lightly. A poorly built snowhole can, quite literally, be a deathtrap. The location chosen is crucial, and while you don’t have to be an architect to construct such a shelter, you need sufficient knowledge of how ventilation works to avoid suffering from suffocation or carbon monoxide poisoning once you fire your stove up or have a candle on the go. Plus, no-one wants to wake up mid avalanche, or to discover the entrance to their cave has become badly blocked by fresh snowfall, or the roof has collapsed.

Cairngorms National Park, where I tried snowholing, is Britain’s largest elevated expanse of wilderness, and it boasts five of the UK’s six highest peaks, the tallest being Ben Macdui, which is both a Munro and a Marilyn. Munro is the name given to Scottish mountains that stand 3,000ft (914m) or more above sea level, whereas a Marilyn is a mountain anywhere in Britain with a prominence (where the peak stands proud of other surrounding summits) of at least 150m (492ft). Named after Hugh T Munro, who surveyed and catalogued them in 1891, there are 282 Munros scattered across Scotland. Systematically summiting and ticking off these peaks is a popular pursuit known as ‘Munro bagging’.

Where to try it

Fantastic hiking can be enjoyed right across the Scottish Highlands all year round, but if you are not an experienced winter hillwalker I can’t stress strongly enough just how dangerous conditions can be, especially if you attempt to stay out in a snowhole. Go adventuring within your capabilities, and seek professional guidance to expand your skill set.

More information on the best outdoor activities for adults in the UK

Caving, Canyoning, and Coasteering… by Patrick Kinsella describes 30 exhilarating adventures around Britain.

For each activity, there’s a comprehensive guide to getting started, the kit you need, skill levels and risk factors, as well as suggestions for the best places to start your adventure, accommodation options and additional online resources.