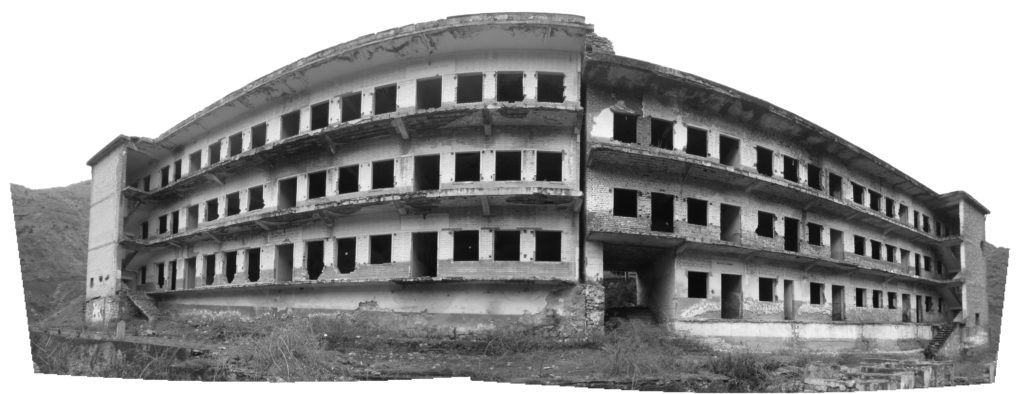

As the UK and the rest of Europe went into lockdown this spring, one surprising window opened up, with the launch of the Spaç prison website offering a digital reconstruction of one of Communist Albania’s most powerful sites of memory.

From our situations of lockdown and isolation, we could now scroll around an experience of lockdown and isolation far more terrifying.

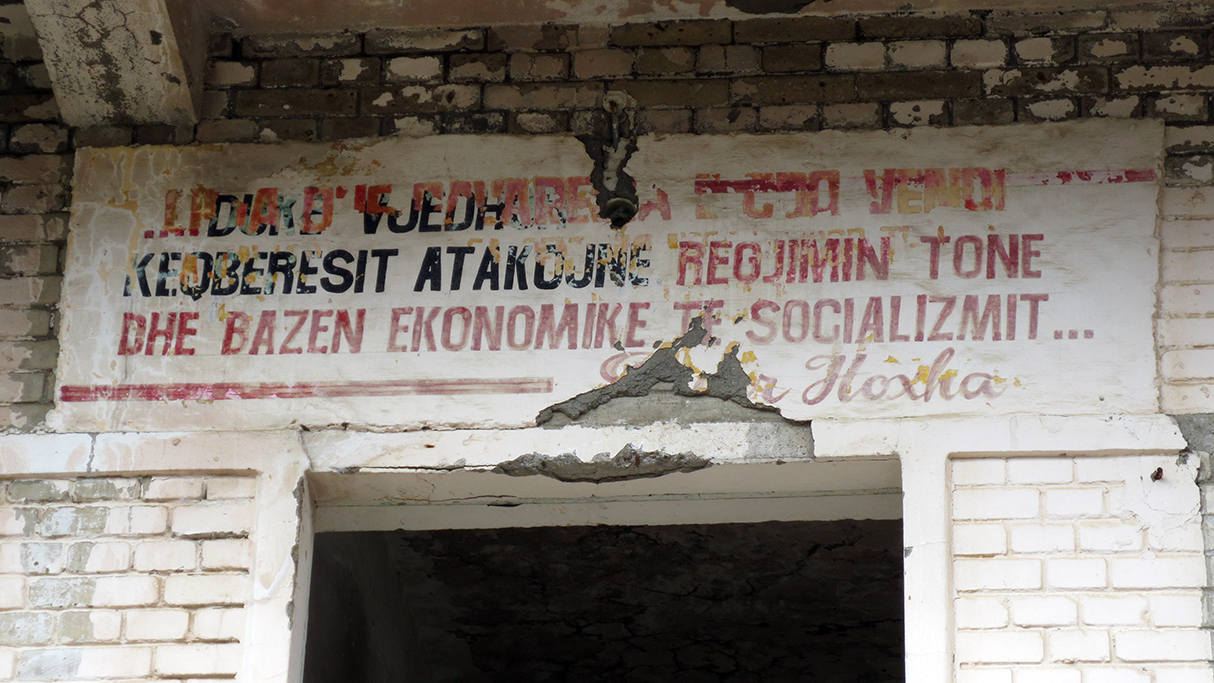

Spaç is not just a name: it’s a concept. It’s a place that’s important to understand because it has come to represent all the places of detention for political prisoners in Enver Hoxha’s vicious dictatorship in this corner of southeast Europe. Fabian Kati, a filmmaker who was held in the prison, tells me ‘Spaç is a symbol’.

He explains that if an Albanian refers to having been held in Spaç they don’t necessarily mean this prison – it’s become a byword for the punishment given to anyone considered subversive.

Daily life for the prisoners used as forced labour in Spaç’s copper mines is described on the website, produced by NGO Cultural Heritage Without Borders, Albania. Clicking on particular buildings brings up relevant oral histories from surviving prisoners. One of them details the vicious solitary confinement cells, each measuring 1m x 1.5m. A prisoner could be held there for an entire month.

Why would anyone want to visit this site? Whether online or when travel becomes possible again and cheap flights to Tirana make it once again an easy weekend destination? For me there are two reasons. One relates to what it was, and the other to what it is.

Talking to Fabian, I realise how much we can learn by coming face-to-face, or even face-to-screen, with the realities of brutal regimes. The most immediate lessons are reminders of the potential for man’s inhumanity to man, and a renewal of our commitment that such evil must not be allowed to flourish.

The subtler lessons are about what can enable people to survive. Fabian identities two things which kept him going for his ten months in isolation under investigation in Tirana, and the 20 months in Spaç. He doesn’t give them the same names as the lifestyle articles in our COVID-19 newspapers, but the focus seems just the same: mindfulness, and a connection with nature.

‘You look at the scratches made by previous prisoners – you look in detail at the cell,’ he says. Who knows whether such intense visual concentration explains or is instead explained by his later work in film.

The second factor from which he drew inspiration was the natural world. Of his arrival in the highlands of Spaç he says ‘the landscape was huge and powerful… the nature there is wild. But having contact with nature is a human need… and you could feel a very intimate sense of freedom just by breathing fresh air.’

His account of his release turns this forbidding landscape into the setting of a fairy story: snow had fallen the night before and the roads were so bad that he had to walk the 3km to the nearest town. ‘It was like walking in Paradise,’ he says simply.

And this is the second of the reasons why the digital reconstruction of Spaç, makes for such compelling internet scrolling: the magnificence of the raw landscape in which it is set.

Visit in summer and basil, marjoram, strawberries and lemon mint are crushed underfoot as you walk the site. Neighbouring Orosh is one of the 100 villages identified by Albania’s government for rural tourism, and nearby there are traditional stone houses you can stay in, local guides to direct you, and hiking trails to follow. Just two hours from Tirana airport, from Montenegro or Kosovo, the area is predicted to see a rise in ecotourism over the coming years.

‘But hopefully not mass tourism,’ says Bledi Hoxha, who works with an NGO called PPNEA (Protection and Preservation of the Natural Environment in Albania). There is anxiety in his voice and he shows me the photograph which explains why.

The picture is the first ever image captured of a Balkan lynx. In 2005 this creature was believed to be extinct but Bledi’s project set camera traps to try to secure visual proof that these magnificent animals had not died out. In 2011 the work finally paid off with this precious photograph. Nevertheless, the creatures’ existence is extremely fragile, like that of so many who’ve clung to life in this wilderness.

I love to think of the lynx here – to know that on the mountain called Munella, only a few kilometres from the ugly history represented in the remains of Spaç prison, a spotted wild cat treads haughtily and gracefully across the rough terrain. It’s a reminder of the beauty that can be found hiding in surprising places.

More information

Elizabeth Gowing is the author of four books about the Balkans as well as Unlikely Positions in Unlikely Places: a yoga journey around Britain, published by Bradt last year. She offers training for individuals and organisations in telling the story of their work and is a regular contributor to Radio 4’s From ‘Our Own Correspondent’. She gives talks – live and via Zoom – to groups in the UK and beyond. More at elizabethgowing.com.