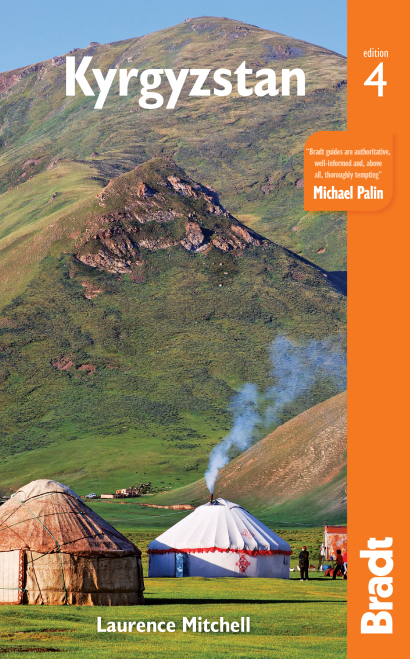

Often referred to as ‘The most beautiful country in the world’, Kyrgyzstan‘s natural wonders are something to be marvelled at. Known for its snow-capped mountain peaks and highland pastures, the country is an outdoors sort of place; that is, if you prefer to spend your time looking at beautiful buildings and drinking espresso in chic cafés then this may not be your ideal destination. If you enjoy trekking, horseriding, birdwatching, camping and visiting remote prehistoric sites, then it most certainly is.

For more information, see our guide to Kyrgyzstan.

Despite the distance which isolated landscapes and current health precautions may entail, a sense of human connection and cultural context is entirely possible and safe to experience within Kyrgyzstan’s splendid natural panoramas, which are marked with traces of human activity.

The history of the tract of land that is now the Kyrgyz Republic stretches back to long before the territory was occupied by nomadic Kyrgyz, cropgrowing Uzbeks or colonising Russians into prehistoric eras and the days of the Silk Road. Punctuating the mountains and valleys that were once roamed by vagabonds and villagers of the past, human traces magically reveal themselves to visitors, if they know where to look.

Bronze-Age petroglyphs and the Fergana Valley

Spread across the top of a mountain in the peaks of the Fergana range lies Saimaluu-Tash, an enormous gallery of 5,000-year-old petroglyphs in a particularly hard-to-reach location.

Evidencing the presence of humans in the Kyrgyz’s territory since the Bronze Age, the embroidered stones are in themselves a remarkable sight, not to mention the sweeping scenery that visitors will encounter when descending from the summit.

From the top of the Kaldama Pass, there are superb views of the valley south towards Jalal-Abad and the switchback gravel-surfaced road snaking down to the Urut-Bashi River. Descending the pass, the sudden change of scenery is abrupt and almost shocking as the vast green expanse of the Fergana Valley edges into view for the first time.

Eventually, after descending to flatter terrain, the fertility of the valley becomes a reality: the fields are full of tall sunflowers and maize in summer and in late August and early September the road itself is used for drying vast heaps of sunflower heads. There is a tangible feeling that another world has suddenly been entered, not just physically but culturally, too, as the figures along the roadside are no longer the Kyrgyz herders predominant on the far side of the pass but, instead, farming Uzbeks busying themselves with their crops.

It is the Saka, however, a warrior clan considered to be a branch of the Scythians, who were the first notable residents in the region, occupying the region from about the 6th century BC to the 5th century AD. A gold-wielding people skilled in agriculture, even Alexander the Great did not succeed in defeating the Saka tribe, whom visitors might try to picture roaming and commanding the land spread before them.

Remnants of the Saka and the Karkara Valley

The Saka are responsible for the large number of burial mounds (kurgani) seen in the north of the country; undulations in the landscape which might otherwise go unnoticed.

Scattered throughout the terrain of the Chui Valley, and likewise the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul and southeast Kazakhstan, are enigmatic tumuli which represent the graves of the Saka warriors of over 2,000 years ago. The San-Tash stones still stand in the middle of a wide, wildflower-rich plain close to a small village within the Karkara Valley.

The long, wide, fertile hollow has lush summer grazing that attracts herders from both sides of the Kyrgyz–Kazakh border, which can be crossed on a number of long-distance treks. The routes can be tackled on foot, or rather magically, on horseback.

Silk Road routes and monuments

Through valley expanses and across vast mountainsides, no landscape was extreme enough to obstruct the Silk Road, the extensive route that connected Beijing to Rome. Horses, camels, travellers and traders with their caravans of exotic commodities took to the road in hopes of passing from the lands of one great empire into another.

In Kyrgyzstan, modern travellers can follow in their footsteps. The Juuku Valley follows the course of one of the old Silk Routes, south over Juukuchak Pass towards the Bedel Pass into China. Along with hot springs, the route is littered with Buddhist rock paintings and the bones of migrants who failed to make the journey.

Meanwhile, high in a hidden valley close to the Chinese frontier lies Tash Rabat, an extraordinary Silk Road caravanserai. One of the most interesting sites in the entire central Asian region, its presence is in complete contradiction to the popular tenet that Kyrgyzstan is all about landscapes rather than historical sites.

A Silk Road monument par excellence, the small but perfectly formed 15th-century stone structure once sheltered an array of merchants and travellers along one of the wilder stretches of the Silk Road. Its location is even more remarkable: tucked away from sight, half-buried in a hillside, up a valley at 3,530m above sea level.

Lake Issyk-Kul and ancient adventurers

The world’s second-largest alpine lake, Lake Issyk-Kul has bathing beaches thousands of miles from the nearest ocean and great hiking in the valleys near Karakol. Flanked by mountain ranges, the region is a state reserve home to several endangered species, including the Tien Shan brown bear and the enigmatic snow leopard.

For the true outdoorsperson, there is plenty of opportunity for wild camping close to the lake; Issyk-Kul’s serene beauty and sweeping views have attracted adventurous spirits for hundreds of years. The lake’s southern shores where visitors might pitch their tents once served as one of the prime routes of the ancient Silk Road, leading west across the Bedel Pass from China before descending to the lake near present-day Barskoon.

The village, linked to the ancient city of Barshkan, celebrated for its riches in the Arabian chronicles, is separated from the Barskoon Valley by grassy meadows perfect for picnics and trails to impressive waterfalls. One of these is lined with two monuments to Yuri Gagarin, in commemoration of his first human voyage into space. A favourite holiday spot of the Soviet pilot, this route will again remind visitors of the region’s longstanding appeal to legendary voyagers.

The Central Tien Shan Mountains

Indisputably the country’s wildest and least accessible region, the Central Tien Shan mountains are no place for gentle mountain hikes. It is in this region, where nomad Kyrgyzs once battled Genghis Khan’s invading mongols, that superlatives abound: the highest mountains, the coldest temperatures, the longest glaciers, the grizzliest mountaineers and the strangest natural phenomena.

This is a region of ice, snow and unexplored peaks – too high and inhospitable even for most hardy Kyrgyz nomads. For this reason, the Central Tien Shan are advisably reserved for either armchair travellers, or committed, experienced mountaineers and those who avail themselves of the support services of guides and porters.

More information

For more information, check out our guide to Kyrgyzstan: