‘You really shouldn’t go alone,’ said an American man sat across from me at a table in a guesthouse in Mazar e Sharif, Afghanistan. ‘Iraqi Kurdistan is very unsafe, especially for lone women.’ We were chatting about our onward travels. From here, my plan was to continue across the border into Iran from Herat, spend a few weeks exploring the country and then cross into either Iraqi Kurdistan or Nakhchivan, a landlocked exclave of Azerbaijan, before returning home.

‘Azerbaijan is much safer,’ he persisted. But all I could think of was the irony – I mean, we were in Afghanistan after all. My cousin had spent time working in Iraqi Kurdistan, and had returned full of praise about the warmth and friendliness of the people he encountered. With this in mind, I chose not to heed the American advice, and I’m so glad I did.

Fast forward a few weeks and I was bidding my final adieu to Iran after crossing the country from east to west and north to south. I arrived at Haji Omaran, the border crossing between Iran and Iraqi Kurdistan, in the middle of a snowstorm. After a few hours waiting for the immigration formalities to be finalised, I walked around the lot, looking for the bus I had arrived on, only to find that there were

now dozens in the park – and almost all completely identical.

Shoot. I should have paid more attention to the licence plate before disembarking, I thought. ‘Bebakhshid!’ I looked to the left and saw a man waving at me. I responded in broken Farsi, and from my accent he immediately clocked that I was foreign. ‘Where are you from?’ he said, flipping into perfect English. ‘I thought you were Persian! It turns out he recognised me from earlier in the day on the bus. His name was Mahdi and he was returning to Erbil, where he worked, having been visiting relatives in Iran.

We re-boarded the bus together, and when we arrived in the city he called a taxi driver he knew and waited with me for him to pick me up. As he said goodbye, he typed his number in my phone in case I needed any help or had any problems during my stay in his country. This wouldn’t be the only time I’d be taken under the wing of a Kurd, showing me a kindness that seemed to know no bounds.

A warm welcome

Etched into the landscape by the Rubar Shakiu River, a tributary of the Great Zab, Dore Canyon is much less well known than the famous ‘Horseshoe Bend’ of Iraq at nearby Rawanduz. Indeed, I had never heard of the canyon until I got in contact with Haval Qaraman, one of the region’s longest-serving tour guides.

I messaged Haval before I arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan. I’d come in way under budget on my trip across Iran and so, rather than explore the area on my own, I decided to see if he was available for a tour. It turned out he was guiding a couple originally from Iranian Kurdistan while I was there, and had only one free day the morning after my arrival.

He had been planning to take his family on a visit to Dore Canyon, but I was more than welcome to join. The only catch? I was asked to take family photos of Haval, his wife, Nagardeh, and his sons, Mohammed and Abdullah. This was a trade-off I was more than happy to take on.

In between family shoots I was given an introduction to traditional Kurdish clothing by Nagardeh, who had brought me my own jli kurdi – the traditional dress worn by Kurdish women – as a gift. This long-sleeved, floor-length dress is often worn over a short cropped vest, with long tails of fabric that extend past the wrists, almost grazing the ground.

As she helped me to put on my dress, Nagardeh also explained about traditional men’s clothing, using Haval and the boys as her models. Typically, men wear a chogah and rank: the chogah is an open-front long-sleeved jacket, worn with a cotton shirt underneath it and tucked into the rank, which are loose-fitting trousers. The outfit is completed by a long strip of fabric that is wrapped around the waist several times as a belt.

The struggle of the Yazidi

Lalish, a valley in the northern reaches of Iraqi Kurdistan, is home to the Tomb of Sheikh Adi Ibn Musafir, the holiest temple in the Yazidi faith. A faith I knew next to nothing about before I arrived in the region.

My driver for the trip into the valley was Aso, a Kurdish man who had married into a Yazidi family. Upon arrival, he explained that I must remove my shoes as a sign of respect. As we walked barefoot across the courtyard towards the temple, we were welcomed by a young Yazidi man who gave me an impromptu introduction to his people, religion and traditions.

The Yazidi are an ethno-religious group that practises a monotheistic faith called Sharfadin, commonly referred to as Yazidism. Sharfadin incorporates elements of Christianity, Islam, Manichaeism, Gnosticism and Zoroastrianism. The religion is centred around one eternal god known as Xwede, who is said to have created the Universe and the seven angels. Tawuse Melek is revered as the leader of the Angels, so appointed because of his refusal to prostrate to anyone aside from God, proving his loyalty.

But the Yazidi have suffered much persecution throughout history, as some Muslims, Christians and other monotheistic faiths equate Yazidism to a form of devil worship as they believe Tawuse Melek to be an incarnation of Satan, rather than an angel. Since the 10th century, the Yazidi have experienced (and survived) some 70 genocides, most recently in the 2014 Sinjur Massacre during which the Islamic State captured and killed over 5,000 Yazidi, mostly women and children.

One of those captured women, our Yazidi guide explained, was Nadia Murad, who survived and has since gone on to found Nadia’s Initiative, an organisation that advocates for survivors of sexual violence and strives to rebuild communities in crisis. Nadia was awarded the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize (alongside Denis Mukwege) for her efforts to end sexual violence as a weapon of war.

The three of us continued to the tomb. Before entering, our Yazidi guide touched a stone figure of a snake on the right side of the doorway and then carefully stepped over the raised sill of the doorway with his left foot, and then his right. He explained that Adi Ibn Musafir was a Sufi leader that settled in Lalish in the 12th century and became a central figure in the Yazidi faith. The local population was impressed by his ascetic lifestyle and performance of miracles, believing that he was the human incarnation of Tawuse Melek.

We entered a long hallway adorned with bright fabrics that reflected what little light was inside the stone building. It connected to three rooms: one housing the Lake of Azrael, where the souls of the dead are brought to be judged; the next being the actual shrine to Sheikh Adi Ibn Musafir, where his tomb is draped in green satin fabric; while the final one holds countless clay pots filled with olive oil which, our guide explained, are used for Yazidi rituals.

Looking back, I was surprised to have received the warm welcome I did – during the rest of my time in Iraqi Kurdistan I came to learn that the Yazidi can be quite closed-off toward outsiders, but rightfully so after the suffering they have endured.

The mountain monastery

of Alqosh

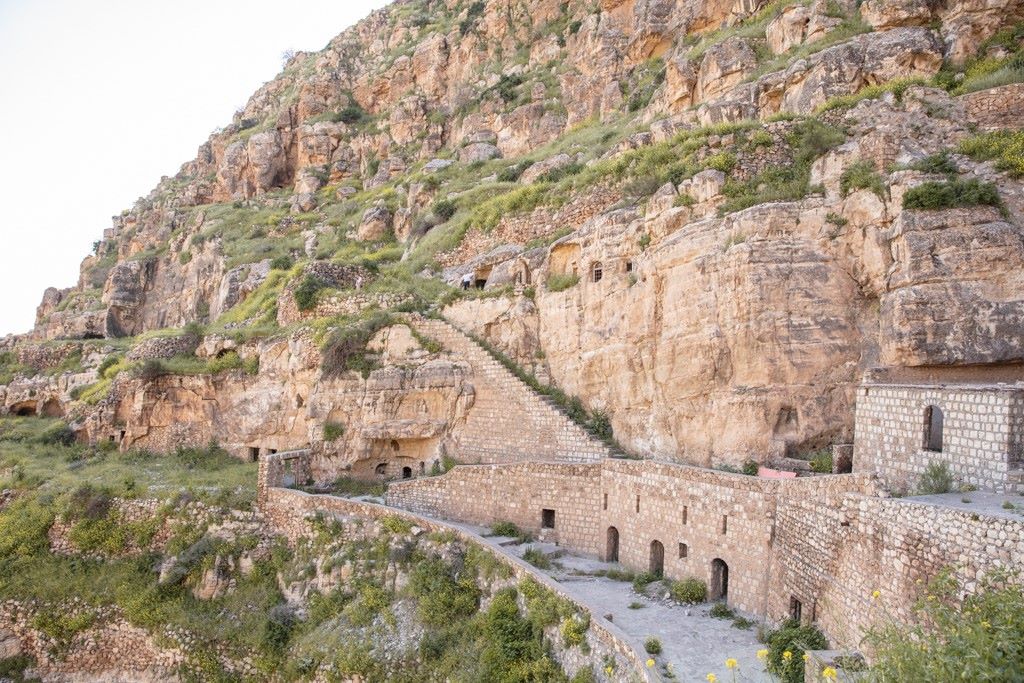

Just outside the small Assyrian town of Alqosh sits Rabban Hormizd Monastery, one of the holiest sites for the Chaldean Catholic Church – another faith that I knew little about. On arrival I was greeted by Ehab Malan, who moved to the monastery three years prior from Mosul and now spends his days welcoming visitors and sharing stories about Alqosh and Rabban Hormizd.

The church is truly a sight to behold, carved directly into the side of the mountain. As I surveyed the magnificent exterior, Ehab gave me a brief introduction to the Chaldean faith – an autonomous church in full communion with the Holy See, the origins of which date back to 1552 following a schism from the Church of the East. Historically, the church has been centred around the Nineveh Plains which are situated to the northeast of the city of Mosul.

We moved inside the rock church, which itself dates from AD640. Ehab told me the story of Rabban Hormizd, who was originally from the Khuzestan region of Iran. He began a journey to Egypt at the age of 18, but it was thwarted by his meeting with the three monks of Bar Idta Monastery. They convinced him to join them at their monastery, rather than continuing on towards Egypt.

That he did, living in and around Bar Idta for 39 years, where he became a monk and then an anchorite. After moving to the Monastery of Abba Abraham of Risha, where he resided for seven years performing miracles, he finally settled on a mountainside near Alqosh. Impressed by his abilities and miracles, the locals set to work building him a monastery.

As we wandered through the tunnels, halls and prayer rooms, Ehab described the recent events that had taken place in the Alqosh area, including his experience of watching ISIS advance across the Nineveh Plains towards the town. It was heartbreaking to imagine such violence and destruction in such a peaceful place.

Bidding farewell in Erbil

I wrapped up my final day in Iraqi Kurdistan in Erbil, or Hawler as it is known in Kurdish. The region’s capital is among the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world, seeing the rise and fall of infamous civilisations such as the Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Achaemenids, Sassanids and many more.

The city is centred around a remarkable ancient hilltop citadel that dates back to around 2300BC, but despite Erbil’s longstanding history, it is quite modern, marrying its ancient sites and 21st-century comforts with ease. It was here at the citadel that I met Pusho and Hakim, a pair of locals who proceeded with pride to give me yet another impromptu tour.

They showed me around the ancient castle and the 13th-century Qaysari Bazaar next door, a large covered maze of a market selling everything from scarves and shoes to yoghurt and cheese. Afterwards they gave me an open invitation to join a picnic with their families and friends – a common occurrence during my time in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Unfortunately, I had to politely decline as I had already made plans that afternoon to join another family I’d met in the city. So much for Iraqi Kurdistan being unsafe.