The last time I was in Orvieto Cathedral I heard that gut-twisting thud of a body hitting the floor; behind me, a woman lay on her back. Fortunately, my first-aid lessons weren’t required as more useful people sprang forward to assist, and as the medics arrived all present breathed a sigh of relief to see her regain consciousness before being whisked away on a stretcher.

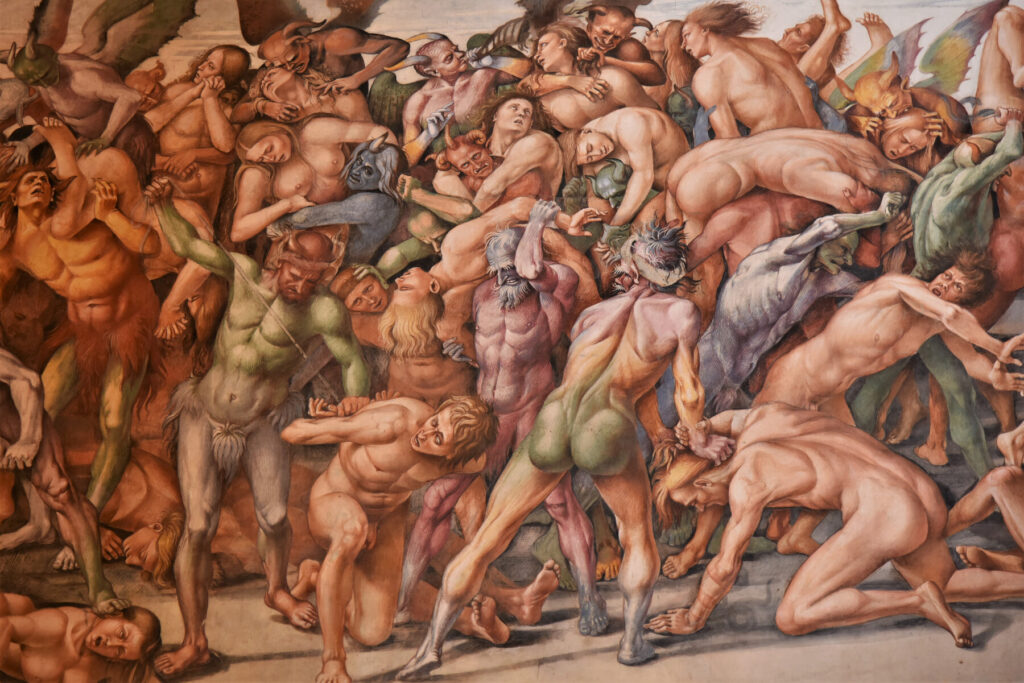

Ever since then I’ve wondered: did she fall prey to the infamous Stendhal syndrome – swooning like the Swiss writer, from an overdose of art and beauty? Or were Luca Signorelli’s vivid frescoes on the Apocalypse just too terrifying? Michelangelo studied them before painting the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

But Signorelli’s, begun in 1499, are even more harrowing, immediate. We see the Antichrist (a unique cameo appearance in art!) preaching to a crowd that includes Dante, Petrarch and Columbus. In the next scene, the newly re-fleshed dead pull themselves up out of the ground in a powerfully surreal scene; next the sinners are herded into hell, among them a special airborne delivery of Signorelli’s mistress who jilted him. It is one of the most gripping nude studies of the entire Renaissance, dominated by the prominent, muscular blue bottom of a demon.

No-one has ever painted bottoms better than Signorelli! Orvieto’s San Brizio chapel has the crème de la crème, but you’ll find other mighty derrières in his Martyrdom of St Sebastian in Città di Castello and in the Flagellation in San Crescentino in little Morra north of Perugia, where our man lingered because he fell in love. A perky Signorelli bum is like a double espresso to the senses.

Umbria and the Marche boast some of Italy’s most sublime art but also some of the quirkiest. Every tiny hill town has its treasure, or something to make you marvel or smile or wonder ‘Lordy, what were they thinking?’

Even their ancient ancestors can make you giggle. Take the polychrome mosaic from the Roman baths of Urvinum Hortense, now in Cannara’s museum. It’s a frolic of little fishermen in ancient baseball hats, using their penises as fishing rods, to carry a bucket of bait; one’s member has painfully caught a crab. Elsewhere they surf on top of amphorae, chasing or being chased by crocodiles and bears.

You can find unusual scenes banned by the Council of Trent which somehow escaped the Counter-reformation thought police, such as a charming 14th-century First Bath of Christ in San Francesco in Offida in the Marche, and in Sant’Agata in Perugia, a kooky three-headed depiction of the Trinity with one set of eyes in the three heads of God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit. Another really bizarre one in San Pietro, as a three-headed woman (presumably because ‘Trinity’ is feminine in Italian).

Perugia’s National Gallery of Umbria is full of masterpieces by Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca and, of course, local man Perugino, who was reputedly a miser and atheist but could paint shimmeringly transcendental religious scenes, often with Perugia’s Lake Trasimeno in the background. But among them is Taddeo di Bartolo’s Descent of the Holy Ghost. Usually in art when the little flames of the Holy Spirit descend on the heads of the Apostles, they look beatifically pious, but Taddeo couldn’t resist a more down-to-earth response: one Apostle is definitely feeling the heat and saying ‘ouch!’

Perugian Benedetto Bonfigli painted the frescoes in the National Gallery’s Cappella dei Priori – scenes of 15th-century Perugia when it looked like Manhattan with all its medieval skyscrapers. It looks gorgeous, but the city was such a nest of pirates that it was dangerous even for popes to visit; three, including the greatest medieval pope, Innocent III, suddenly dropped dead there under suspicious circumstances.

The citizens of Perugia were bad and they knew it. For kicks they would meet in front of the cathedral and stone each other in a game called the ‘Battaglia de’ Sassi’. But God was constantly punishing them with plagues and epidemics, and in 1259 a local hermit had a vision that self-flagellation was the only cure. The bishop of Perugia thought it was a splendid idea and ordered a two-week whipping orgy.

The Perugini formed brotherhoods and wore long white robes split open down the back and anonymity-preserving hoods with two ghostly eyeholes – and their kinky, creepy figures often appear in art, nearly always sheltering under the cape of a giant Madonna superwoman. Bonfigli painted their gonfalons, or processional banners, which they would hold during the flagellation walkabouts, and they pop up in several churches in the area. The gonfalon in Santa Maria Nuova is one of the best, with its vengeful Jesus flinging down arrows on wicked Perugia, in spite of a whole clutch of saints begging him to stop. It was such a hit among the locals, the brotherhood had to protect it with a metal grille.

But my favourite super-Madonna is by Tiberio Assisi in Montefalco: Our Lady holds a club like Hercules, about to wallop a little doe-footed devil who came to nab a naughty boy after his mother exclaimed ‘May the devil take you!’ The look on the devil’s (‘Hey, lady, I was just doing my job!’) face is priceless.

Montefalco also boasts one of many fresco cycles in the region based on the legends of St Francis, all inspired by the extraordinary ones by Giotto (or not – it’s the longest controversy in art history) in Assisi’s Basilica of San Francesco. The deeds of the beloved patron saint of Italy, animals and ecology, here by Bonozzo Gozzoli, are full of delight: who can resist the gentle Francis preaching to the birds and fish, shushing the noisy ass, and shaking paws with Brother Wolf in Gubbio – where, by the way, no-one was surprised during the restoration of a church when they found the skeleton of a large wolf. It’s all true!

Even in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, the ultimate Renaissance dream house in the ultimate little Renaissance city, home to Raphael’s melancholy portrait of La Muta, and Piero della Francesca’s haunting, uncanny Flagellation, there’s an unforgettable little squirrel nibbling a nut – perched on a balustrade, in Duke Federico da Montefeltro’s Studiolo, with its mesmerising trompe l’oeil intarsia.

I’m always subject to onset Stendhal syndrome in Urbino, and after drinking in my favourites I usually tend to race through the rest, but last time on guidebook duty I made an extra effort to look at everything and went upstairs, straight into a nasty piece of late 16th-century work by Mannerist Federico Zuccari called Porta Virtutis.

What the heck? Here we see The Artist (represented by virtuous, wise Minerva) standing in a triumphal arch, while horrid Envy sprawls on the floor, covered in vipers as she grabs the ankle of a man with donkey ears – a certain Paolo Ghiselli of Bologna (and relative of Pope Gregorio XIII) who refused to pay Zuccari for an altarpiece. The other demons have the faces of other Bolognese artists that Zuccari didn’t like. The pope, furious, sent our man into exile, and only let him back into the Papal states thanks to the good offices of the Duke of Urbino, which is why this crazy painting hangs here.

Other works in the Marche have stories we’ll probably never uncover. Seek out Castignano, where the church of SS Peter and Paul has an anonymous ruined but bizarre early 15th-century fresco of the Last Judgement, dominated by a blond Christ with eyes out of the Children of the Damned. Gymnast angels dressed in red perform loop-de-loop stunts on the mandorla that surrounds him.

On one side are records of eclipses. Like many Marchigiano towns, Castignano had a Templar commandery (did those mumbo-jumbo-loving knights have something to do with it?)

Anything by the brush of Carlo Crivelli and Lorenzo Lotto, the Venetians who spent most of their careers in the Marche, is worth seeking out, not only for the sumptuous gorgeousness of their colour but the good chance of finding something quirky.

Carlo Crivelli was a master of exquisite 15th-century refinement, clear lines and rich colours. Almost inevitably he painted his sweet, sad-eyed Virgins under garlands of fruit and flowers – in which his signature trick was to insert a large phallic cucumber. You’ll find Carlo’s ‘cuke’ in the Pinacoteca Civica in Ancona, and another in his gorgeously luminous Sant’Emidius polyptych in Ascoli Piceno’s cathedral (although the best is his Annunciation with Saint Emidius in London’s National Gallery where he didn’t even bother hiding it in a garland, but left a big old warty cucumber lying front and centre on the pavement by an apple, as if someone spilled their shopping).

Why? As far as I know no-one else, except perhaps his artist brother and follower Vittore (who also left numerous fruit-and-veg-adorned works in the Marche), ever painted them. They are not on anyone’s list of canonical religious symbols. I wonder if they were a memory of his misspent youth? Carlo, after all, had to leave Venice after serving time for kidnapping a sailor’s wife.

And I will drive many a twisty kilometre to see anything by Lorenzo Lotto, renowned for psychologically insightful portraits, but who also painted some of the finest and quirkiest Renaissance religious works in the Marche. Jesi has some in the first category in the wonderful Palazzo Pianetti, including his uncanny Annunciation of 1526 with a Virgin-startling angel hovering in a private whirlwind, dressed in the gauzy drapery that reveals – yes, in case you were wondering, angels do have one – his belly button.

Now drive less than an hour to Recanati, where the Museo Civico has an Annunciation that Lorenzo painted eight years later, during which time he had a bit of a rethink. Now God the Father, off stage in Jesi’s Annunciation, dives like an Olympic swimmer through the doorway; the angel, down on one knee behind the Virgin, seems to be frightened himself, gesturing ‘Look out!’ Mary, unusually, in Annunciation scenes, is looking straight at the viewer. She seems calm, wise, maybe a little scared, accepting her destiny.

But it’s her little cat, annoyed by all the ruckus that upset her nap and jumping out of the scene as fast as she can, that always makes me laugh out loud.

More information

For more information on Umbria and the Marche, check out our guide: