One of the first things you notice when visiting Bologna is how every street is lined with arcades, or portici. A representative ensemble of 12 segments has now been inscribed as a UNESCO Heritage Site, incorporating a wide range of unique porticoes, built with diverse purposes, materials and structural elements.

The originals date from the 12th century, when the comune, faced with a housing shortage compounded by the presence of 2,000 university students, allowed rooms to be built on to existing buildings over the streets. However, the loggia below, even if on privately owned land, was a legally determined public space everyone was allowed to use.

Over time the Bolognesi became attached to them and the shelter they provided from the weather. Along with the absurdly tilting Two Towers, they are the city’s soul, its identity; to the Bolognesi, their special world is the pianeta porticata, the ‘porticoed planet’. The city claims 70km (including the single 4km portico that climbs up to San Luca), more than any other city in the world.

Via Zamboni

Northernmost of the radial streets, Via Zamboni connects the Two Towers to the university and the Porta San Donato. Originally called Strada San Donato, it was renamed to honour Luigi Zamboni, a law student at the university who distinguished himself as a spy and soldier against the pope in the tumults that accompanied the French Revolution. Before his death in a papal prison, Zamboni invented the red-white-and-green tricolore that would become the Italian flag.

In the Middle Ages, one of the noble family compounds in the area belonged to the Bentivogli, the family who would rise to become Bologna’s tyrant bosses. They built their great Renaissance palace on this street, setting the scene for it to become the city’s most fashionable address. The Bentivogli were expelled in 1507, but in the decades that followed, as Bologna enjoyed its last flush of Renaissance prosperity, this street filled up with more imposing palaces.

The university was already here, and narrow Via Zamboni became the place where dons and dukes rubbed shoulders. It certainly is one of the narrower streets in Bologna, and made even narrower by the porticoes that lined it – but Bologna is a city where even the wealthy have to grow accustomed to living in the shadows.

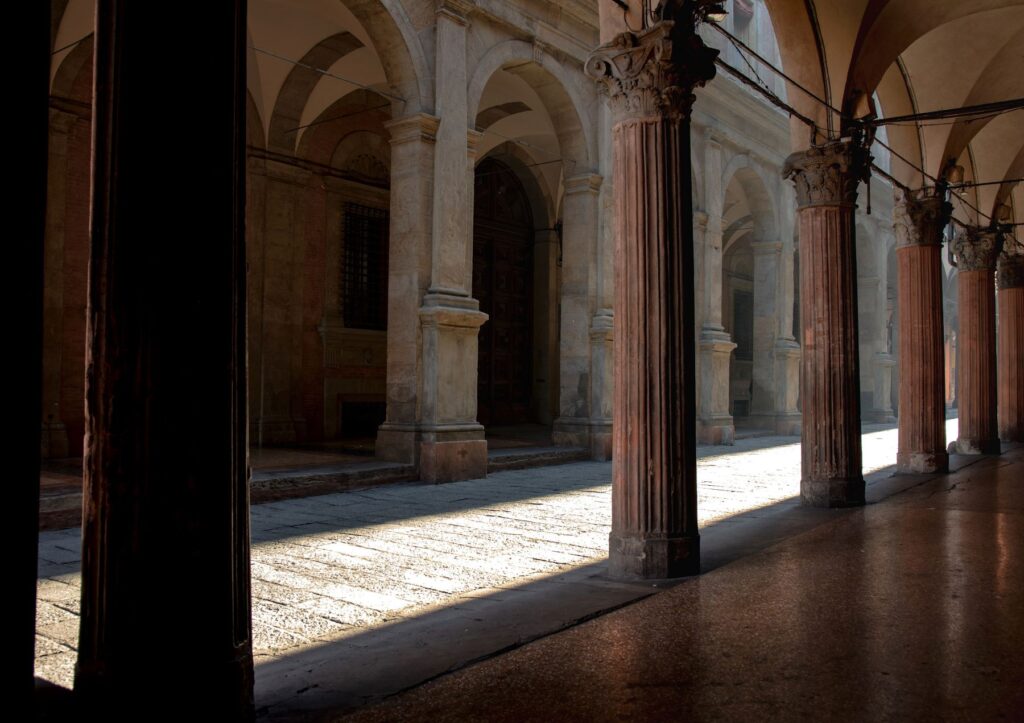

San Giacomo Maggiore

Begun in 1267 by an order of Augustinian hermits and completed in 1344, Romanesque San Giacomo Maggiore is hugged by a graceful portico, arguably the most beautiful in Bologna, with Corinthian columns and a terracotta frieze. San Giacomo was the parish church of the Bentivogli, who built their family chapel in the 1460s, then filled it with some of Bologna’s finest Renaissance art.

Giovanni II hired Lorenzo Costa to paint the frescoes – the Triumph of Death, the Apocalypse and a Madonna Enthroned – in the midst of Giovanni II and His Family, a fresco commissioned in thanksgiving for the big boss’s escape from hired assassins.

Casa Isolani

This is one of the best-preserved 13th-century houses left in Bologna, with one of the city’s oldest and highest porticoes, supported on wooden beams. The adjacent Corte Isolani, a charming covered street with a string of little courtyards, dates from the 1450s.

The Isolani family, who trace their origins to the Lusignan rulers of Cyprus during the Crusades, still own both today, and they have restored the Corte as an arcade of shops and cafés.

Portico di San Luca

In the southwest corner of the centro storico is the Porta Saragozza, the starting point of the portico to beat all porticoes – the Porticato, winding 4km up to the Sanctuary of the Madonna di San Luca, with 666 arches along the way, a kind of eccentric embellishment only possible in the Age of the Baroque (it was also quite a boost to the local pilgrimage trade).

Begun in 1674 and finished in 1793, each arch was financed by a different family, religious group, guild or corporation. Each set up a plaque by their contribution, although many have vanished or resemble ghosts of their former selves. Not even Bologna’s numerous students of the occult can explain why there are exactly 666 arches. That at least is the traditional number; people often try to count them, and they never get the same answer twice.

Portico dei Servi

The city’s Gothic jewel, Santa Maria dei Servi is preceded by a rare and lovely quadroporticus mingled amid the porticoes of the Strada Maggiore. This is in the Early Renaissance Tuscan style, with slender columns and iron braces; one side dates from the 1390s, while the rest had to wait until 1855.

The church was a little slow too; begun in 1346, according to a design by Friar Andrea da Faenza, and assisted by Antonio di Vincenzo, it wasn’t completed for another two centuries. Typical for Bologna, however, they never got around to the façade.

Palazzo Bolognini

The Palazzo Bolognini (1517) is a palazzo senatorio – as the Bolognesi call their most impressive palaces – designed for the ‘senatorial’ class of the most powerful families.

This one is known for its graceful portico, decorated with a series of busts in between the arches, some by Alfonso Lombardi. Everything above that level is a 19th-century restoration.

Archiginnasio

The long, porticoed façade to the left of San Petronio is the former home of the university, the Archiginnasio, its walls covered with the escutcheons and memorials of famous scholars. Bologna’s university, although the oldest in Europe, was not provided with a central building until 1563; before then classes were held in public buildings or cloisters.

The Archiginnasio is the building Bologna got for its money instead of the expansion of San Petronio; the Counter-Reformation popes, always worried about heresy and political opposition, apparently wanted to keep all the intellectuals here in one place where they could keep a close eye on them.

After the university expanded to its new quarters in 1803, the Archiginnasio became the municipal library, the Biblioteca Comunale, which always has a selection of old books, manuscripts, prints and sketches on display.

More information

For more information on Emilia-Romagna, check out Dana and Michael’s guidebook: