The Island is large enough to lose yourself on, but small enough for this not to matter: just keep walking and that creek you amble along will eventually wind its way to a village pub or, failing that, another slice of a part of the world that is easy on the eye.

Mark Rowe author of Slow Travel: Isle of Wight

At the narrowest point of the Solent, between Hurst Castle in Hampshire and Fort Albert on the Island’s northwest edge, the Isle of Wight floats barely a mile off the coast of the British mainland. Yet with no commercial airport or tunnel you must take to the sea to reach it: that requirement alone demands that, in a literal sense, you must slow down and begin to shed the hurried pace of everyday life before you have even arrived. Then, when on dry land, you will find little reason to quicken your pace.

The Island is large enough to lose yourself on, but small enough for this not to matter: just keep walking and that creek you amble along will eventually wind its way to a village pub or, failing that, another slice of a part of the world that is easy on the eye.

There are so many wonderful reasons to visit the Isle of Wight. From the haunting coastline around Newtown and Shalfleet where woodland edges dip their roots in the ebbing shallows and mudflats, to the Norman town of Yarmouth with its fine cafés and delis. The red squirrels pretty much anywhere you look, the extraordinary jumble of geology that makes up the Undercliff or dawn flooding the Solent, viewed from the shingle spit that keeps Seaview dry. Then there’s the spectacle of a peregrine falcon darting along the guillotined edges of Tennyson Down, the mournful call of a nightjar in Brighstone Forest, or stumbling across dinosaur fossils. Each one has a strong claim on the heart strings of visitors.

The cheek by jowl nature of seaside paraphernalia and natural drama on the Island often borders on the surreal. Just a few minutes’ cycle from the archetypical resort of Sandown you can lean your bike against a hedge and watch an egret hunting for fish in a serene mire; you might catch a red squirrel out of the corner of your eye, furiously clambering upside down along an overhanging branch. Elsewhere, you might heave yourself up the vertiginous slopes of Ventnor Downs, taking in a sweeping coastline that pulls away to the middle distance. But while one moment you may get carried away with the ‘being at one with nature’ ethos, the next you may encounter a Victorian seaside amusement park. Some visitors can find such a combination intrusive; others have certainly been known to sneer. To me – and for most Islanders – they seem to rub along perfectly well. Far from being mutually exclusive, they are all part of the Island DNA.

Bradt on Britain – our Slow Travel approach

Bradt’s coverage of Britain’s regions makes ‘Slow Travel’ its focus. To us, Slow Travel means ditching the tourist ticklists – deciding not to try to see ‘too much’ – and instead taking time to get properly under the skin of a special region. You don’t have to travel at a snail’s pace: you just have to allow yourself to savour the moment, appreciate the local differences that create a sense of place, and celebrate its food, people and traditions.

for more information, check out our guide to the Isle of Wight

Food and drink on the Isle of Wight

Food

When it comes to the Slow approach, it seems those early Romans – who built no towns but did establish at least seven farmsteads on the Island – were ahead of their time. While the boar and deer are gone, other resources they latched on to remain in abundance and explain why the Isle of Wight supports an extraordinary range of local, independent food producers. You’ll find everything from fresh fish to cheese, tomatoes, cherries, flour, sweetcorn, pumpkins, broccoli, sprouts, bread, jams, dressings, vinegars and ice cream here.

At the last count, there were more than 50 local food producers on the Island, all either independent or family owned. ‘There are no big companies or businesses here to take up lots of space,’ says Will Steward, who runs Living Larder, which delivers boxes of fresh fruit and vegetables around the island. ‘That creates opportunities for local and smaller operators. If you’re from the Island or have lived here for a long time then you feel an obligation to make it a better place. I think that is why there are so many local food producers.’

A good example of this is the meat reared by the Isle of Wight Meat Co. The emphasis here is on quality rather than quality – their meat is hung on the bone in a salt chamber for up to eight weeks – and visitors to the website will be struck by the statement, especially from a butcher depending on meat sales for their livelihood, that ‘we don’t have to eat meat every day’. The change in emphasis came in 2019 when farmer-owner Andrew Hobson decided to move away from supplying restaurants and supermarket chains and instead supply the local market with Island-produced pork, beef and lamb. For his efforts, Andrew was awarded Beef Innovator of the Year at the 2020 British Farming awards. Note that the company does not have a farm shop as such but does operate a click and collect system for online orders, with options ranging from peppered pork and shish kebabs to boxes of different cuts of meat.

The company recently merged with Greef’s Biltong (formerly based in Seaview). This specialist product is produced by Zimbabwe-born Nick Greef, who learnt his trade as a child on his father’s cattle farm. The dry-cured meat is lean and high in protein – for meat eaters, it’s a good alternative to Kendal mint cake if you’re out on the downs all day – and free of nitrates and emulsifiers.

Like the Isle of Wight Meat Co, many of the Island producers aren’t geared up to sell from their production sites (which are often their homes or farm steadings) so instead you will find them available in shops across the Island. Probably the best known is Minghella Ice Cream, founded by Edward and Gloria Minghella, and which produces high-end Italian-style ice creams and sorbets. (Their son, Anthony, achieved worldwide fame as a film director and playwright.) Others include The Fruit Bowl run by Alistair and Barbara Jupe in Newchurch. The couple produce jams and preserves – plum, loganberry and cherry, rhubarb, ginger and apple, among more than a dozen varieties, and are aiming to become the UK’s first ‘green’ jam producer. Their three cre smallholding accounts for 90% of the fruit they use.

Another local producer, Godshill Orchards, grows cherries, apricots, greengages and plums. Meanwhile, Wight Crystal collects, treats and bottles water from a spring at Knighton and uses their profits to fund the training and employment of people with disabilities on the Island.

Drink

There are two vineyards on the island. Rosemary Vineyard is open for tours and has a well-stocked shop where you can buy or sample a spicy white muscatel and oak-flavoured red sourced from Alsatian grapes. Adgestone Vineyard grows around 20 tons of grapes that produce 27,000 bottles of wine. You can take a tour of the estate with an audioguide before finishing off with an inspection of the cellars and, the reason anyone really comes to a vineyard, the opportunity for tasting.

There are also three breweries on the island (Goddards Brewery, Island Brewery and Yates), all of which offer a solid selection of craft beers. The Isle of Wight has also caught on to the UK gin obsession with the emergence of Mermaid Gin.

Where to stay on the Isle of Wight

For information about accommodation, see our list of the best places to stay on the Isle of Wight

What to see and do on the Isle of Wight

Bembridge

Jane Austen may have visited the Isle of Wight but none of her heroines ever exclaimed ‘Oh! Bembridge!’ in the way they were inclined to breathlessly talk of Bath or Lyme Regis. They really should have done. Bembridge has everything you’d want for an elegiac holiday: gorgeous beaches to wander along while pondering the meaning of life, an abundance of high-quality shops to potter around and a slightly faded – but not too faded – ambience.

What to see and do in Bembridge

High Street and around

The soul of the village is to be found in the High Street, which features several excellent independent stores, from a baker and a butcher to a fishmonger and a wholefood shop; it is with good reason that Bembridge won Countryfile Magazine’s ‘Village of the Year’ award in 2018.

Located on Church Road, at its junction with the High Street, the church of the Holy Trinity is made of Purbeck stone and features an elaborate clock and lancet windows. It was built in the mid 19th century and replaced an earlier incarnation (a rare, failed effort by John Nash) that, made of the more friable Bembridge stone, began to collapse.

Half a mile south of the village centre, at the very end of High Street, is the lonely Bembridge Windmill. The last of its kind on the Island, this is the archetypical windmill, standing 38ft high with four sails pinned to a circular, tapering four-storey structure built from stone rubble, all topped with a wooden cap.

Built in the 1700s, it operated as a flour mill and flourished until the advent of the Bembridge train line, which brought cheap flour from afar. In spring and summer you can climb the stone steps within the tower and take in the remarkably complete wooden machinery that survives from its days of practical use, including a turning wheel, windshaft and grain bins. There’s also the chance to learn about the milling process in the small exhibition within the windmill. A small kiosk outside sells hot drinks, cakes and ice creams.

Bembridge beaches

The village has three beaches, all of which are fetchingly attractive, but their geology is unsuited to lounging as they comprise stones, pebbles and shells. On the western shoreline, Bembridge Beach tumbles into the coast from the spit at the edge of Bembridge Harbour; softer sand reveals itself at low tide.

To the east, Bembridge End Lane Beach, which bumps into the pier and lifeboat station, has a little more sand. Both of these beaches are perfect for beachcombing, with attractive backdrops of woodland framing the view inland. The pier, meanwhile, is 250yds in length and juts out into the water around the eastern periphery of the village and to some extent marks a logical geographical boundary to the community.

The second of the Island RNLI lifeboat stations (the other is in Yarmouth) stands at the far end of the pier; the station can be visited in summer. The coast remains accessible to the east of the pier, where it fragments into a series of wave-cut platforms around the appropriately named Ledge Beach: Bembridge Ledge, Long Ledge and Black Rock Ledge and the marshy shingle of the Foreland. Rock pooling comes into its own here at low tide.

Another opportunity facilitated by low tide is a walk all around the Bembridge coast, from the lifeboat station to the harbour and the Pilot Boat Inn, a distance of around 1¼ miles that takes around 40 minutes. Beyond the ledges, and further to the southeast of Bembridge is Whitecliff Bay, a 200yd crescent of sand and shingle tucked below a high ridge and which offers a rear-view vista of Culver Down. The beach is accessed by steep paths via the holiday park behind it. From the shoreline you can also gain tidal access to Horseshoe Bay.

Marshes

From the village windmill, it’s almost impossible to resist walking down the hill for half a mile to meander through the (often watery) hinterland of RSPB Brading Marshes, exploring the small wildlife-rich Centurion’s Copse that is visible from on high. This silent, open expanse of reclaimed marshland and wetland habitat stretching between Bembridge and Brading has a touch of magic about it as the land tumbles away to become spirit-level flat.

Flocks of sparrows and wagtails and even a wayward pheasant may shimmy among the trees. Look out for little egrets perched by a pond and lapwings, stylish birds with a raffish ‘quiff ’ or quill. Meanwhile, alders dip their roots in the streams and the mires are dark and still.

Though it feels like a vast woodland, you can explore the network of paths here inside an hour. Paths thread this way and that through the copse, past reed beds and clumps of woodland and hedgerows thick with old oak, ash and hazel, home to buzzards, yellowhammers, red squirrels and the embattled green woodpecker. You pass raised, dyke-like banks smothered with mosses of a fluorescent green that verges on the luminous, while a hilly curtain, in the form of the chalk edifice of Bembridge Down to the south and the woods above Brading to the west, give a faint impression that this is a lost world.

Bembridge Harbour

The Eastern Yar finally meets the sea at Bembridge Harbour, a vast expanse of water spanning 250 acres from the beach at St Helens on the north bank to Bembridge Point on the southern side of its mouth. At low tide, the estuary shrivels to a trickle and any vessel within is marooned until ebb turns to flow. When empty, the harbour is a stirring spectacle of muds, mosses and wide-open skies. The harbour has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest on account of these intertidal mudflats, sand dunes and, offshore, underwater sandstone ledges.

Watery flora you might catch sight of along the shallow shores include the submerged slender stems of the nationally rare foxtail stonewort, while on land you may see thrift, autumn squill and the delightfully named suffocated clover (the name comes from the tightly packed, overlapping nature of its white stalks and flowers). You can only imagine how vast this seascape must have seemed to arrivals and locals in Roman times when the estuary was five times larger than today.

The harbour is extremely easy on the eye. Woods overlook it from both headlands and a line of beach huts adds a parti-coloured dimension to the view. Behind the harbour is a magical sliver of salt marsh that makes a joyous playground for herons and egrets, while turnstones and waders such as sandpipers feast in the sandbanks on the seaward side.

Behind the boats and across the narrowest point of the harbour are the remnants of the old sea wall, long collapsed, its sea-smashed foundations spanning, in intermittent fashion, the middle waters of the harbour and visible at low tide. The new sea wall is visible too and bisects the harbour, running in parallel to its predecessor; it is walkable at all but the highest of high tides and is a handy way to walk from Bembridge to St Helens Duver.

Brading Roman Villa

Brading Roman Villa offers an absorbing insight into one of the Roman Empire’s more unheralded conquests: the Isle of Wight. Set back to the southwest of Brading, the eponymous villa is beautifully laid out, remarkably intact and sheltered within a wonderful independent museum.

What you explore are the remains of the West Range, a high-status house that was complete by the early 4th century and occupied continuously for nearly 300 years. It’s the last and grandest of the buildings on the site. Two other ranges have been identified: one to the south, which was built around the time of the Roman invasion in 43 AD, and a more substantial north range dating to 200 AD. The unexposed foundations of both are marked in chalk outside the main building. In the 6th century, for reasons unknown – perhaps political unrest – it fell into disrepair and slipped out of local memory, forgotten for the best part of 1,300 years until it was discovered by a local farmer in 1880.

The museum walls are built around the outline of a substantial part of what was a winged corridor villa, with a private family wing and a separate space for entertaining guests. The eyecatchers are the substantial mosaics, along with pieces recovered from excavations, including a bronze door key lock. There’s a Medusa mosaic, here positioned to ward off evil-doers, as well as a depiction of a who’s who of Roman and Greek mythology – Achilles, Ceres and the constellations of Perseus and Andromeda. The centrepiece is a huge fractured Bacchus, the god of wine, and some other unusual mosaics – considered to be of exceptional quality – that include a domed house and a cockerel-headed creature, known as a Gallus.

Brading is a unique site: hundreds of Roman villas boasted a Medusa knocking around or a wine-quaffing Bacchus, but the cockerel-headed mosaic is the only one of its kind ever found and has long teased the finest antiquarians who have tried to unpick its true meaning.

What the Gallus does surely disclose is that this was the owner’s way of showing that he was a well-to-do, educated man. Other than that, however, we know nothing about the owner, though the discovery of evidence of ploughs, quern-stones and wagons indicates that barley and wheat were grown and processed here, pointing to him earning his wealth as a merchant or a farmer, rather than a soldier, as no evidence has been found of an army presence. It’s possible the Romans by then had been long accepted by local people, which also implies that benign trade had gone on well before the invasion.

The villa was perched close to Brading Haven, at that time a deepwater port that dispatched goods to the Continent or southeast England. There was a rationale for this, for the Romans also had an interesting geographical perspective. To the Roman eye, the Isle of Wight made little sense if looked at in the conventional north–south way that we do today (with Cowes at the top, Ventnor at the bottom). For them, it was far more practical to view the Island as if looking along its plane, from west to east; in this view along the spine of the Island, the ‘top’ – Brading, Sandown – points directly along the Channel to France and seamlessly on to the northern European coastline and the mouth of the Seine, Boulogne and estuaries of Germanic lands. From there, a right-hand turn down any major river would sweep the traveller towards Rome. It’s reckoned the return journey could have been done within two months.

Brading Roman Villa is extremely good for children, with opportunities to dress up and role play and for them to engage in their own self-assembly mosaics. The Forum Café is also excellent, offering big bowls of soup and excellent cake, with panoramic views across Sandown Bay. There’s also a gift shop featuring both Roman-themed items and Island-wide crafts.

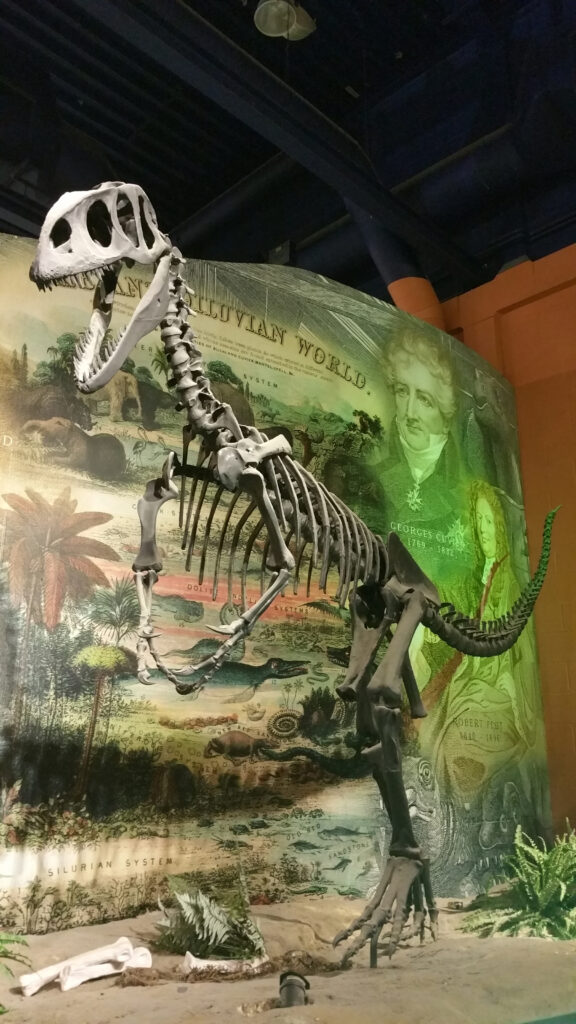

Dinosaur Isle

Dinosaur Isle must be one of the UK’s most underrated visitor attractions. Viewed from a distance the building is a striking shape featuring two protruding poles and an arched canopy intended to resemble a pterodactyl (though you may be unable to resist a possibly ungracious comparison to a pair of narwhal tusks or knitting needles).

It’s something of a bizarre gem where you find both an important fossil collection and a main hall containing genuine skeletons and bones, alongside supersized dinosaur mannequins. Fossils from 35 types of dinosaur have been found on the Isle of Wight, and in total the museum’s catalogue extends to more than 40,000 fossils gathered from right across the Island, with around 1,000 on display at any time.

The walk-through collection of Island finds is a highly informative eye-opener into the sheer range of animals that once roamed what is now called the Isle of Wight, including many of a more recent vintage, dating back a mere 10,000 to 15,000 years. Objects on display include the tusks of a mammoth and a hippopotamus; fossil teeth and femur of a straight-tusked elephant; the lower jaw of Bothriodon, a pig-like hippopotamus; and the jaw of another pig-like amphibious mammal, Elomeryx porcinus.

In the main hall, giant vertebra and casts of Jurassic Park-style footprints share cabinet space with tiny fossils of large-winged termites and water spiders that resemble the smeared imprint of flies on your car windscreen. Eye-catching exhibits include the skeletal display of a Neovenator dinosaur – its femurs each weigh three stone – along with the femur and humerus (each more than 3ft in length) and gastroliths (stomach stones) of a 45ft sauropod (these long-necked creatures were the largest dinosaurs ever to have lived).

Several knowledgeable palaeontologists – some amateur, some professional – are on hand to shed light on the displays and there is a working laboratory on view, which works on the same principles as an open kitchen in a restaurant. Staff like to point out that Yorkshire, the rival to the Jurassic Coast, has promoted its ‘Dinosaur Coast’ but you could count the number of bones the county has on the fingers of one hand. The captions display a refreshing candour that is absent from more pompous and self-important establishments; these regularly include statements about their more mysterious remains that have yet to be fully identified, in effect shrugging a shoulder and admitting ‘we don’t know’ or ‘we’re not sure’.

The museum runs year-round guided fossil walks on Yaverland Beach and further afield. As is the case at the museum, the guides are affable, neither precious nor guarded with their considerable knowledge, and keen to inspire future generations of palaeontologists.

Look for fossils

Having brushed up on the facts at Dinosaur Isle, the next step is to hunt down some fossils for yourself. Stare for long enough at a map of the Isle of Wight – with a ridge through the middle and gently tapering east–west points – and it can come to resemble a large slice of vertebra from a fossilised backbone. A coincidence maybe, but the Island’s primordial soup was perfect for fossilisation of animals such as dinosaurs, which inhabited the Island for around ten to 15 million years.

Dinosaur fossils can be found around much of the coast, but one of the Island epicentres of discovery are the cliffs below Culver Down and Yaverland, where you will find what are termed Early Cretaceous and Wealden group rocks. Spend an afternoon searching for these hidden treasures and soak up the island’s gorgeous natural scenery at the same time. It’s win-win.

Newtown

The minuscule hamlet of Newtown stands at the heart of a National Trust-owned nature reserve. It is unusual in that it is a rare example of a medieval new town that failed economically due to a combination of plague, changing river flows and those ever-marauding French neighbours. In the early and mid 14th century, Newtown was the most important port on the Isle of Wight – something that seems rather improbable to the modern-day visitor – with an oversized town hall the only surviving nod towards the community’s former stature.

While Newtown has withered over the centuries, it escaped development and regeneration and many of its original green lanes and small paddocks have survived, along with a grid-like street pattern radiating out from the shore like those at Yarmouth and Newport.

Make sure not to miss the Old Town Hall (National Trust), a red-brick house resting on large pillars and dating to 1659 (though the town gained borough status much earlier, in the 13th century). As Newtown’s stature and importance waned, so did the fortunes of the hall, to the point that it became a town hall with no town. In fact, by the end of the 16th century, the ‘town’ had become one of the notorious ‘rotten boroughs’. This shoddy status was removed in 1832 when the seat was abolished by the Great Reform Act.

The town hall was rescued from physical collapse in the 1930s by the intervention of the eccentric Ferguson’s Gang, a group of masked women who remained anonymous but devoted their time to raising funds to buy property for the National Trust. They would burst into Trust meetings and plant a sack of cash on the table, Robin Hood style, with strict instructions on how it should be spent.

Just up the road from the hall, the church of the Holy Spirit is the epitome of the rural idyll, with a symmetry to its Gothic porch and arched windows that gaze out upon a lush churchyard. Unlike the hamlet in which it stands, the church offers a relative injection of young blood, having only been built in 1835. Indeed, so lovely is the church that architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner described it as ‘the finest early 19th-century church on the Island’.

A short walk from the path to the west of the church leads through Newtown National Nature Reserve to the shoreline; road’s end is a boardwalk to an attractively positioned bird hide. The lagoon-like waters of the inlets of Newtown Creek were once saltpans until breached by a fierce storm in 1954. In spring and summer the whole area is a delight, fringed with the blue tinge of sea aster and the purple of sea lavender. The adjacent coastal meadows are infilled with green-winged orchids and classic hay meadow species such as the superbly named corky-fruited water-dropwort, whose white flowers sit atop a bolt-upright stem that’s 3ft in height, and, in a nod to one of the trades that once was active here, dyers greenweed (confusingly, yellow in colour), which was used for dyeing cloth.

The England Coast Path (a nationwide project) is being implemented on the Island and is expected to improve access around Newtown. The existing Island coast path route frustratingly keeps the hiker at arm’s length from the coast at times, but the enhanced extensions will give access to more coast via the hay meadows behind the hides overlooking the creek and Newtown River. In the meantime, you can access more of the coast here via footpath CB16A (by the town hall car park) which leads around the south side of Newtown. The coastline is gorgeous – soft, green rolling hills tumbling to the foreshore, while the New Forest makes for a wooden-framed horizon across the Solent.

Red Squirrel Trail

If a cycle trail can be a poster child for two wheelers, then it would be the Red Squirrel Trail. This lasso-shaped route explores the east of the Island and is popular with families. The basic loop runs for 13 miles from Newport to Sandown and Shanklin, with the ‘noose’ of the lasso representing the extension up through Newport towards West Cowes and into Parkhurst Forest.

About 95% of the route is off-road, ranging from flat, former train lines to mud and puddles, and is suitable for trail bikes and mountain bikes, and bicycles with chunkier tyres. The route is really excellent for all age groups, so younger families can easily manage it with a trailer. If you’re looking for a day’s family cycling, consider hiring bikes to go from Newport to Dinosaur Isle and the Wildheart Animal Sanctuary on the edge of Sandown.

In the direction of Newport, the trail has a useful northern spur along the west bank of the Medina that offers hassle-free access to Parkhurst Forest. The trail includes a 3¼-mile loop through the woods. All the cycle trails within the forest are along gravel trails.

If you have the time, leave your bike for a while and continue along the sole walking route which leads from the car park for three-quarters of a mile to a log cabin-style hide. Here you can sit and stare up at the tree canopy, though try and manage expectations as there’s no guarantee that the red squirrels will be co-operative. The knack to spotting them is to look high in the pine branches: pick the outer edge of a branch and follow it inward towards the trunk and be alert for any movement.

Seaview

It is really worth heaving yourself out of bed early one morning and strolling along the shoreline at Seaview, to understand why such an apparently unoriginal and self-evident name actually fits the Isle of Wight village wonderfully well.

As dawn eases its way through the twilight, look for bats flitting in and out from the nearby eaves of the graceful flint-built buildings that characterise the village. In the clear, still dawn half-light, these airborne mammals can seem surreal, rather like broken umbrellas being jerked up and down by an invisible hand. Lines of cormorants fly east along the Solent from their overnight roosts, honking geese following in their slipstream. It’s a timeless scene – if you had to date it you might feel you have stepped back 100 years – and all that seems to be missing is a lady twirling a filigree-trim parasol while carrying a poodle under her arm, escorted by a wheezing, portly gentleman taking the sea air on doctor’s orders.

A non-stop walk around Seaview takes perhaps ten minutes (you have little more to explore than an anti-clockwise loop starting on the High Street, which leads down to the Esplanade from where you turn back uphill along Seafield Road), but it would be easy to dawdle a whole day here, spending time in either of the two good hotels, the handful of cafés and two excellent shops, all of which are centred on or just immediately off, the High Street. Some visitors come for a week and get no further than here on the Island.

The coast path runs around the edge of Seaview, often tracking a sea wall that keeps the Solent at bay, and there are uninterrupted views of Ryde East Sands and the shingle-sand mixture of Springvale Beach. The defences, for now at least, keep the sea from overwashing the smattering of new and rather exposed houses that sit hard above the beach. Follow the coast path a few hundred yards west from Seaview and you’ll come to the Alan Hersey Nature Reserve, named after a former local councillor who passionately cared for the local environment. The woodland is small but runs inland alongside a reed-fringed lake and is an enchanting place, especially on an early still morning when, if you tread quietly, you may catch a green woodpecker foraging on the ground. To the dismay of today’s local wildlife lovers there’s a proposal – vigorously opposed – to convert the reserve into a yacht park.

A narrow coastal road and sea wall separate the reserve from the adjacent Seaview duver. A duver (pronounced to rhyme with ‘cover’) is a geological feature comprising a spit of sand and shingle and this one spreads out in rectangular fashion on the seaward side of the sea wall. Both the reserve and duver are part of a Special Protection Area, an environmental accolade awarded to species-rich places, and you will almost certainly see herons and little egrets. In addition, nine species of bat have been recorded here. The duver provides an important habitat for sandwich, roseate and little and common terns, along with wintering ringed plover, teal and black-tailed godwit.

Had you been here in 1887 you would have had something more grisly to gaze upon, for that year the steamer Bembridge struck a whale near St Helens Fort. The unfortunate cetacean was exhibited in a tent on the beach at Seaview.

Tennyson Down

Just about every visitor to the Isle of Wight will gravitate to the extraordinary beauty of Tennyson Down, which in turn is something of a gateway to other adjacent and equally special places of interest. At sea level you’ll find Freshwater Bay’s vast shingle banks and sea stacks. On rather higher ground, Tennyson Down – and the Island itself – slips away to the crumbling chalk pinnacles of the Needles. Here, amid shudderingly high cliffs and eye-popping sea stacks, you’ll encounter important military history at the Old and New Batteries.

The area is also historically of great cultural importance for it was called home by both Alfred, Lord Tennyson and the pioneering woman photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. Their exquisite former abodes are open for nosing around. By way of contrast, but of arguably equal cultural significance, this is also where Jimi Hendrix famously, if briefly, laid his hat.

Beginning at sea level immediately to the west of Freshwater Bay, the down rises inexorably for a mile to a 482ft-high brow before descending gently and levelling off as it heads towards its dramatic crescendo in the form of the Needles, the westernmost point of the Island. Along the downs’ entirety, its southern flanks are guillotined by the sheerest cliffs imaginable, where kestrels hover close by.

Exploring the down can feel like navigating the deck of a ship that is cresting a wave, for while the land rises remorselessly up from Freshwater Bay, it also tilts this way and that. Ravens lurch upwards, sideways in kite-like manoeuvres; in great contrast, the northern flanks slip away into bucolic pockets of scrub and deciduous woodlands of oak, sycamore, beech holly and hazel, where thorny scrub has been left unchecked to mature into hedgerows and woodland. The downland is extremely varied with little coppices here and there and thick clumps of heather and gorse, which break up what could otherwise be a uniform landscape of cattle-nibbled grass. You will occasionally see horseriders galloping its broad bridleways.

The initial goal when walking Tennyson Down is to reach the Tennyson Monument, a plinth topped with a marble Celtic cross found at the summit of the down. The monument, erected in 1897, is both an unofficial beacon for sailors and a tribute to the poet. Some elegiac lines from Tennyson’s poem, Crossing the Bar, are inscribed on the base:

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar, When I put out to sea.

The ‘bar’ in question is a treacherous sandbar, which, along with its adjacent shallow waters, ferry masters must navigate on their journey to the mainland. It lies in the Solent, to the north of the downs, and can be seen easily at low tide. You can almost imagine spotting Tennyson here too, his ghost pacing the sweeping downs, wrapped in his signature cape and sporting his trademark broad-brimmed hat. Never short of an apt turn of phrase, Tennyson described the air found upon the downs as being worth ‘sixpence a pint’.

Ventnor

Until barely 200 years ago, the area now known as Ventnor comprised only a few fishermen’s cottages and a mill but the seaside location, seclusion and balmy temperatures saw it promoted as a health-giving location and development as a seaside resort began in earnest from around 1830. Before long, the Isle of Wight town was referred to as Mayfair-by-the Sea, with millionaires swanning around hotels that boasted the new wonders of the age such as hydraulic lifts and palm courts.

Today the town divides, very roughly, into three distinct areas: terraces of houses gaze down from on high; the next tier down comprises the town centre, with a one-way road system centred on the High Street with its array of independent shops; below here, Shore Hill descends steeply in a zigzag past the Winter Gardens and the Cascade Garden to the Esplanade and the beach.

Here and there you will see grand mansions, classic Victorian townhouses, Mediterranean palms and other Italianate features. Properties are built mainly in the local greensand stone but there are plenty made of brick and of flint (in Victorian times, flint was considered second-rate but it was cheaper; you’ll notice many houses have sandstone frontages but their back and sides are pockmarked with chunks of flint). The sea is constantly imposing its presence on the town and, in an attempt to resist erosion, 30,000 tons of Mendip limestone have been deposited along the shore, starting to the west of town, and extending into a mile-long sea wall to the east.

What to see and do in Ventnor

Ventnor and District Local History Museum

Before heading for the Esplanade, it’s definitely worth popping into the Ventnor and District Local History Museum, which is another one of those little gems, packed with nuggets of information about the town’s past. You’ll see just how much the town has changed over the years as its development is captured by the works of local artists on display. Shipwreck tales also abound – spare a thought for one of the unluckiest (or foolhardy) victims, Richard Tatton-Groves, who drowned after returning to the stricken Underley in 1871 to retrieve a pet bird. The other 30 passengers and crew survived.

Esplanade

The town beach’s sand is soft and there are several cafés and restaurants close by at which to pause. The 6ft needle standing upright by the beach is a gnomon, the spire that casts a shadow on a sundial. It was given to the town by Sir Thomas Brisbane (a governor of New South Wales who gave his name to the eponymous Australian city). A marker used to stand on the opposite side of the Esplanade and at midday the gnomon would cast a shadow upon it.

A little further west along the Esplanade is a conspicuous resin-coated beach hut, the original hut built by the Blake family, who made their money from the 1830s by hiring out beach chairs and bathing machines. These machines were works of wonder and were deployed in ranks along the water’s edge during Victorian times. The emotionally rigid visitors of the time would have been scandalised at the sight of anyone exposing flesh or, heaven forbid, swimming in the water. Instead, single-sex machines had to be hired, along with an attendant.

Ventnor Fringe Festival

Every July, the town runs its mini-version of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, the Ventnor Fringe Festival, which includes an eclectic range of entertainment from pop-up street comedy to puppet shows in a launderette. More than a hundred shows take place over six days and several acts then head up to Edinburgh for the Fringe Festival. Ventnor also runs a carnival every September. Stay a while and you may hear a local mantra: ‘Keep Ventnor Weird’. That’s not to be taken too literally; it really just means that those mining Ventnor’s artistic seam are keen for the town to resist any attempts at gentrification.

Ventnor Park

Although small in size, Ventnor Park, lying just to the west of the town, may be less heralded than the adjacent botanic garden but the grounds regularly win national and regional Britain in Bloom awards and are a dizzying collage of exotic Mediterranean pines and sturdy British specimens. One magnificent oak resembles a candelabra, with branches reaching upwards like imploring fingers from the palm of a hand.

Steephill Cove

The descent to Steephill Cove is down a zigzag of uneven steps but it’s worth persevering with (the only other way into the cove is by boat). You can easily spend a day here – some people base their entire holiday at the cove and, given its seclusion and the fact everything you need is at hand, it’s easy to see why. At sea level and just above the sloping sandy, pebble-dotted beach and breakwater boulders that are somehow cobbled together to form a loosely curved promenade, you will find fishermen, a handful of cottages, brightly coloured canopied deckchairs, beach huts and hauled-up lobster pots.

There won’t be a slot machine, car or burger in sight. Resident fishermen have been practising their tradition since the 1400s and still bring fresh crab and lobster ashore daily (weather permitting); the legacy is a handful of good eating options that can save you from lugging your own food down the steep steps to the bay.

Street art

Don’t leave Ventnor without taking in the magnificent spray-paint mural on the High Street near the eastern edge of town, which features a sea creature morphing into the Isle of Wight, the Needles by its feet. The three-storey work was created by Phlegm, a painter of world-renown in street artist circles. It’s an unforgettable spectacle and should finally dispel any lingering misconceptions you might have that Ventnor is simply somewhere people go to retire.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Isle of Wight:

Related articles

These are some of the more unlikely locations for vineyards in England… hicc!

From farm parks to old-fashioned railways.

From medieval castles to Edwardian Arts-and-Crafts architecture.

From boutique accommodation to beachside pubs.

From luxurious yurts to family-run holiday parks.

From Victorian town houses to Elizabethan manors.

From working farms to converted salesrooms.

From a lawnmower shrine to walls lined with cuckoo clocks – and everything in between.

These are some of our favourite green spaces to wander in England.