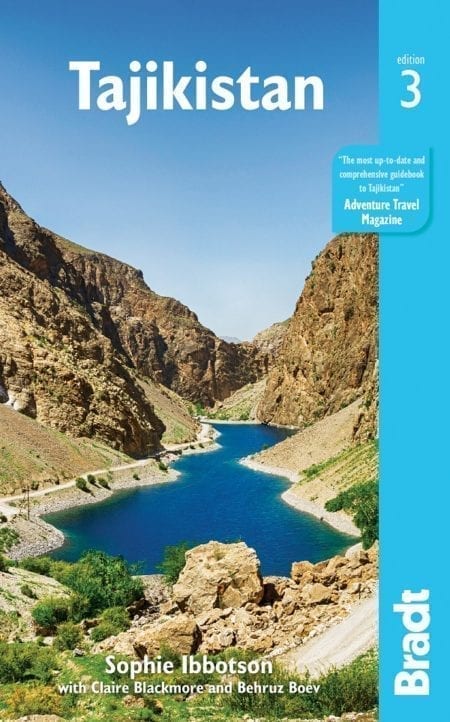

Nature has been kind to Tajikistan, bestowing the country with breathtaking beauty: here you’ll find mountains, glaciers, lush river valleys and dense forest, supporting a bewildering array of flora and fauna.

Sophie Ibbotson, author of Tajikistan: the Bradt Guide

Tajikistan is the roof of the world. When you first start to read about the country, this same cliché pops up time and again.

Initially it may seem that such repetition shows a lack of imagination among writers (at least a century of them, and counting), but when you finally come to stand atop a peak in the High Pamir, staring down as a concertina of meringue-like peaks unfolds beneath you, or even swoop down to land on a scheduled flight, holding your breath else the pilot brushes the snow off the mountaintops with the underside of the plane, you too will find the same phrase tripping off your tongue. Tajikistan is the roof of the world.

Nature has been kind to Tajikistan, bestowing the country not only with breathtaking beauty but with a moderate climate too. Mountains and glaciers, lush river valleys and dense forest support a bewildering array of flora and fauna, including the famed (but sadly camera-shy) Marco Polo sheep and the even rarer snow leopard.

Hot springs – either the result of geological faults or miracles enacted by ancient holy men – are scattered through the valleys, their warm, mineral-rich waters both a pleasant diversion on a journey, and, for local Muslims, important pilgrimage sites. Alpine meadows bursting with the bright colours of spring flowers create a patchwork rainbow that streaks across the horizon, the pastures welcome picnic spots for road-weary tourists and grazing goats alike.

For more information, check out our guide to Tajikistan

Food and drink in Tajikistan

Tajikistan does not have a long tradition of eating in restaurants: it was nigh on impossible during the Soviet period due to food shortages and the fact that people were encouraged to eat collectively in the work canteen. This has changed in urban centres, particularly as families choose to host wedding feasts and other large celebrations in restaurants rather than at home, but you will not find the density or diversity of restaurants typical in some other parts of Asia.

Restaurants in Tajikistan (particularly those situated outside of Dushanbe) typically have a limited menu of Russian and Tajik dishes. It is rare for everything listed to actually be available. If the restaurant is not fully booked for a celebration you won’t need a reservation, nor to wait for a table. Service may be chaotic but it is generally good-natured.

Sit-down places to eat typically fall into three categories. There are large, often fairly ghastly, restaurants which only cater to groups, either private parties or tour groups. These serve a buffet or set menu, and they may or may not welcome independent guests.

Second, and infinitely preferable, are Western-style restaurants which have multiple tables, a menu, and cook to order. You can wander in off the street and sit down, as long as it’s during opening hours. In larger cities you’ll have a choice of different cuisines – Dushanbe’s restaurant scene is looking decidedly cosmopolitan these days – and you can expect a reasonable level of customer service. You will be expected to leave a tip: 10% is standard.

Thirdly, you have local cafés, which are unpretentious and generally offer good value for money. These typically serve Tajik cuisine or other easily prepared snacks, and depending on the establishment you will either order from the counter and then take a seat, or wait for someone to come to you. There is unlikely to be a menu, and staff may well not speak English, so be prepared to look around at what other people are eating, point and smile. A tip, though not expected, is always appreciated.

More common than restaurants and cafés are street-side food stalls: from American fast-food stands with burgers and fries, to smoking grills and the vinegary smell of shashlik and onions wafting down the road, making your stomach rumble. Women with trays piled high with savoury pastries saunter through markets and the lobbies of office buildings; trestle-tables nearly buckle beneath the weight of freshly baked bread. The local fare tends to be tastier (and cheaper) than attempts at foreign food.

Tajik cuisine

Tajikistan runs on bread and tea. Wherever you are, from a customs post to a shepherd’s hut, there will always be a kettle on the boil and a few china tea bowls filled with a light, steaming tea.

Tajik cuisine is definitely central Asian (plenty of grilled meats and dairy products), but with an influence from Afghanistan and Russia too. The national dish, as far as there is one, is plov or osh, an oily rice-based dish with shredded carrot, meat and occasionally raisins, roasted garlic or nuts. Plov is eaten with the hands from a communal plate at the centre of the table.

Equally popular is qurutob. Balls of salted cheeses (qurut) are dissolved in water and poured over dry, flaky bread. The dish is then topped with onions fried in oil. It may be accompanied by laghman (noodle soup with mutton). Tajik restaurants tend to offer diners quite a limited menu.

Every meal is accompanied by round, flat bread called non. Non is treated almost reverentially: it should not be put on the floor, placed upside down or thrown away. If it has turned stale it should be given to the birds.

Common snacks include manti (steamed meat dumplings), somsa (triangular pastry with a meat and onion stuffing) and belyash (deep-fried dough stuffed with minced lamb).

Dairy products feature heavily in Tajik cuisine. In addition to the qurut are chaka (sour milk) and kaymak (clotted cream), both of which are eaten with bread. Western-style yoghurt, including bottled yoghurt drinks, is popular for breakfast. If you are in Tajikistan in late summer and early autumn, the country is bursting with fresh fruits. Roadsides stalls sell watermelons the size of beach balls; the sweet, juicy pomegranates are a glorious shade of pink; and you can also enjoy grapes, apricots, apples, figs and peaches.

Health and safety in Tajikistan

Health

The medical system in Tajikistan is seriously overstretched. The quality of medical training has fallen since the end of the USSR, many doctors have left to find work abroad, hospitals are run-down and equipment is out of date. Outside the major cities there is also a shortage of drugs and other medical supplies.

If you are ill or have an accident, you will be able to receive basic emergency treatment in Dushanbe, Kulob or Khujand but will then require evacuation (MEDEVAC) to a country with more developed medical infrastructure for ongoing care. One of the best hospitals in the country is in Khorog, opened with the help of the Aga Khan Foundation, with doctors who have often trained or worked overseas and tend to speak a good level of English.

Most towns in Tajikistan have aptekas, small pharmacies selling a range of generic drugs. You do not need a prescription to purchase medication, but should read the instructions carefully or get someone else to explain them to you.

Do not drink tap water – it can be a serious health hazard. Use bottled water, which is widely available, or even better, take a reusable water bottle and filter with you. Water purification tablets can be used when trekking or camping.

Safety

Tajikistan is generally a safe country for tourists to visit. All parts of the country are accessible to foreigners, though you will need a permit to visit GBAO. It is advisable to check the FCO travel advice before travelling, however, as issues such as Covid-19, natural disasters, and border openings/closures may influence how and when you travel.

Female travellers

Tajikistan is generally a safe place to travel, whether you are male or female. That said, you should exercise the usual personal safety precautions and dress modestly, especially in conservative rural areas. It is not culturally acceptable to wear revealing clothing (including shorts, vest tops, or T-shirts which reveal your stomach) in Tajikistan. If in doubt, look at what ordinary women are wearing on the street, and dress with commensurate modesty.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality has been decriminalised in Tajikistan but there is, to our knowledge, no open gay scene in Dushanbe. Many people in Tajikistan are deeply conservative, especially when it comes to the issue of sexuality, and homosexuality is still often seen as a mental illness (a hangover from the Soviet period).

If you are travelling with a same-sex partner, you would be wise to refrain from public displays of affection and be cautious when discussing your relationship with others: it is often simplest to allow others to assume you are simply travelling with a friend. Double rooms frequently have twin beds, so asking for one room is unlikely to raise eyebrows in any case.

Travellers of colour

Travellers of African descent, and those with red or blond hair and very pale skin, tend to stand out while travelling through Tajikistan, despite millennia of cultural mixing in the region. You may be stared at on the street, or approached to have your photograph taken, especially in smaller towns and rural areas. Many of these interactions are out of curiosity and easily, even humorously, managed. However, alcohol-fuelled aggression is not uncommon, so try to avoid physical confrontation if possible.

Travelling with a disability

People with mobility problems will experience difficulty travelling in Tajikistan. Public transport is rarely able to carry wheelchairs, few buildings have disabled access, and streets are littered with trip hazards such as broken paving, uncovered manholes, and utility pipes. Hotel rooms are often spread over multiple floors without lifts and assistance from staff is not guaranteed. If you have a disability and are travelling to Tajikistan, you are advised to travel with a companion who can help you when the country’s infrastructure and customer service fall short.

Travel and visas in Tajikistan

Visas

Unless you are a CIS national, you will almost certainly need a visa to enter Tajikistan. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs now offers an electronic visa for tourists that can be processed online through a special website. The process usually takes up to five business days, requires a scanned copy of your passport (with at least six months’ validity remaining) and costs US$50, plus an additional US$20 if you wish to visit the GBAO.

As of 1 March 2020, you can now apply for an e-visa with multiple entries, which is ideal if you’re planning a wider trip through central Asia and need to enter Tajikistan more than once.

Getting there and away

However you choose to travel, Tajikistan is not a particularly easy country to reach. Land borders open and close somewhat erratically, flights are irregular at the best of times and cancelled at the first sign of bad weather, and wherever you arrive from by train you’ll require a passport full of visas and the patience of a saint.

By air

The vast majority of visitors arrive in Tajikistan on a flight to Dushanbe and this is, on balance, the easiest way to travel. Unless there are extenuating circumstances, you will need to have a visa before boarding the plane and may be prevented from flying if you do not.

Direct flights to Tajikistan tend to come only from the Middle East, Russia and the other CIS countries, although national carrier Somon Air is starting to open up new routes, including a new direct flight to New Delhi. It is likely, therefore, that if you take a flight originating in Europe or the USA you will need to get a connection in one of the regional hubs (Almaty, Istanbul or Moscow).

The safety record of many of central Asia’s airlines is such that they are prevented from flying in European airspace, although Somon Air does serve a number of more localised routes, including to Moscow and Istanbul.

By train

There is a certain romance attached to train travel, and if you have the time to sit and watch the world pass by at a leisurely pace (very leisurely in the case of the old Soviet rail network), it is still a viable way to reach Tajikistan. Regardless of where the train originates, you will need to ensure you have a valid transit visa for every country en route, as well as a visa for Tajikistan.

Ticket classes are categorised in the Russian style. First-class or deluxe accommodation (spets vagon) buys you an upholstered seat in a two-berth cabin. The seat turns into a bed at night. Second class (kupe) is slightly less plush, and there are four passengers to a compartment. Third class (platskartny) has open bunks (ie: not in a compartment) and, if you are really on a very tight budget indeed, a fourth-class ticket (obshchiy) gets you an unreserved and very hard seat. Bring plenty of food for the journey, and keep an eye on your luggage, particularly at night, as theft is sadly commonplace.

There are three main train routes to Tajikistan. There are two trains a week in each direction between Moscow and Dushanbe, a weekly service between Moscow and Khujand, and a twice-weekly service between Samara (Saratov) and Khujand. All these services pass through Tashkent; the Dushanbe train also passes through Samarkand. Tickets to Moscow (second class) start from just over US$145 and the trip takes four days.

The train timetable for the whole Russian rail network (including central Asia) is online at www.poezda.net. The Man in Seat 61 also has detailed information, including personal observations, about train travel in the former USSR.

By road

Our preferred way to enter Tajikistan is through a land border, not because customs and immigration make it a particularly easy or pleasant experience, but because of the freedom having your own transport gives you once you finally make it inside.

Border crossings open and close regularly, often with little warning, and some crossings are open only to locals and not to foreigners. Keep your ear to the ground and, if in doubt, contact a tour operator or Tajik consulate before confirming your travel plans. We have previously ignored our own advice, with the result that we had to drive overnight from Panjakent to the Oybek crossing north of Khujand to leave Tajikistan before our visas expired. We would not recommend you follow suit.

When to visit Tajikistan

Climate

Tajikistan’s climate is continental, and varies dramatically according to elevation, so when to visit Tajikistan depends on where you are going. It is the wettest of the central Asian republics, but again rain and snowfall depend on location, from the relatively dry valleys of Kafiristan and Vakhsh (500mm a year), to the Fedchenko Glacier, which receives in excess of 2,200mm of annual snowfall.

Temperatures in Tajikistan’s lowlands range on average from -1°C in January to as much as 30°C in July. The climate is arid, and artificial irrigation is required for agriculture. In the eastern Pamirs it is far colder: winter temperatures frequently fall to 20° below freezing, and the average temperature in July is just 5°C.

When to visit

Tajikistan explodes into life in the spring. As the snows subside and the higher parts of the country once again become accessible, the lower mountain slopes and pastures are a riot of colour. Tajiks celebrate Navruz, the Persian New Year, on the spring equinox, 21 March, with feasting, dancing and adrenalin-charged games of buz kashi, Tajikistan’s answer to polo.

In the summer months, when temperatures in Dushanbe and the lowlands soar to uncomfortable levels, the Pamirs come into their own: you can drive the Pamir Highway without the risk of snow from June to September, and at the same time climb the higher peaks. Glacial meltwaters have slowed, the rivers are no longer in spate and, though an occasional blizzard may still catch you unawares, you can join the shepherds as they drive their flocks up into the mountains to grow fat on the grasses of high pastures.

Tajikistan marks its Independence Day on 9 September, and the crops in the Fergana Valley and other agricultural areas are harvested. The fresh fruits at this time of year are divine. Nights in late September will already be cold in the Pamirs, and from October roads in the higher mountains will be impassable due to snowfall and ice. As the autumn progresses the emerald-green trees that form ribbons through the bottom of each river valley turn almost overnight to a fiery red and orange. In Tajikistan’s lower regions, which include most of the north and southwest, there’s a bite to the air come nightfall, but bright sunshine still warms up the day.

The winter is hard in Tajikistan, with many communities cut off and, if the harvest has been poor, dangerously short of food. For those with money, however, the snowfall marks the start of the ski season, and the Takob ski resort becomes busy with day trippers from Dushanbe.

What to see and do in Tajikistan

Ajina Tepa

Some 12km to the east of Bokhtar are the archaeological remains of Ajina Tepa, the 8th-century Buddhist monastery from which the remarkable Sleeping Buddha (now in the National Museum of Antiquities in Dushanbe) was uncovered in the 1960s.

Though all of the finds were removed to Dushanbe or museums in Russia, it is still possible to see remnants of the 2.5m-thick mud-brick walls that protected the internal courtyard and monastic buildings. Approximately 1,500 artefacts have been excavated from the site since the initial archaeological dig in the 1960s, a testimony to the monastery’s importance and opulence.

Ironically, despite its holy affiliations, the name Ajina Tepa itself means ‘Devil’s Hill’, and fragments of gargoyles and other demon-like sculptures were found among the ruins; scholars believe these items served to scare away opponents of Buddhism.

Dushanbe

With its style caught somewhere between stark Soviet-era and laid-back Western café culture, Tajikistan’s capital city feels more like a market town than a metropolis. Its skyline is scraped by a handful of mid-rises and accented by the world’s now second-tallest flagpole, and the parks and gardens have benefited from some lush landscaping and impressive water features.

Without centuries of Silk Road wealth or the patronage of indulgent emperors, Dushanbe’s façades have historically been far humbler than those of many of its central Asian rivals, though that is changing with the controversial push towards bigger, bolder buildings: the opulent Navruz Palace and immense National Museum of Tajikistan among them.

But the geography of the valley, the paths of the rivers, and the acres of parkland and trees still define the shape of the city and give it a quietly bustling feel. In the heart of the Hisor Valley, at the confluence of the Varzob and Kofarnihon rivers, Dushanbe (meaning ‘Monday’) takes its name from the weekly market, which historically took place on this site.

Dushanbe’s geographical isolation may have contributed to its less starkly Soviet architecture, but many of the more notable buildings from the country’s decades as a republic of the USSR – including the central post office and the much-loved Vladimir Mayakovsky Drama Theatre – have been demolished in recent years and replaced by even larger commercial structures financed by developers from across Asia.

Still, many of the buildings in the centre of the city are predominantly low-rise, brightly painted, and hark back to an earlier Russian style. The tree-lined avenues, and the manicured parks and cafés in squares, create an almost continental feel, and the clutch of monuments and museums speak to Tajikistan’s push for a post-independence architectural legacy.

The best things to see and do in Dushanbe

National Museum of Antiquities

The largest and most important museum in Dushanbe, this cultural highlight houses artefacts covering 3,000 years of Tajik history. Recently renovated, the museum is laid out according to a mixture of geography and chronology. Some of the more important items are labelled in English, and the staff are keen to tell you about the items on show.

The museum’s greatest draw, the Sleeping Buddha, takes pride of place on the second floor. Since the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, this 16m-long statue is the largest remaining Buddha in central Asia. Dating from around ad500 and sculpted from local clay, it was discovered at the Buddhist monastery of Ajina Tepa in 1966 and had to be moved to Dushanbe in sections.

Rudaki Park

Sandwiched between Rudaki and Ismoili Somoni, this sprawling park is a well-maintained space with numerous flower beds that come into bloom in early summer and are a colourful addition to the landscape right through to autumn. In September, the beds are a riot of red and orange.

Whichever path you take through the park you’ll be unable to miss the world’s second-tallest flagpole. Rising 165m above the park, this controversial structure cost US$3.5 million to build and was erected as the world’s tallest in May 2011 as part of celebrations to commemorate 20 years of Tajik independence. Three years later, the city of Jeddah erected a 170m pole, snatching the flag for Saudi Arabia.

At its heart lies the Palace of Nations, an imposing structure that can be seen from across the city. With its golden dome, it is home to both President Rahmon and many of the government ministries. Though photogenic, the palace guards are a little jumpy about foreigners wielding cameras, so if you wish to take a photo then do so subtly. This is not the place to set up your long lens on a tripod.

Other photo opportunities in this area are the ostentatious golden statue of Ismoili Somoni with its two uniformed guards, the elegant, marble Independence monument (aka Stele), and the rather more tasteful Arch of Rudaki. The statue of Rudaki stands beneath a colourful mosaic arch and is reflected in the pool of water below. Don’t miss the immense artificial waterfall built into the side of a hill overlooking the racetrack and the river.

National Library of Tajikistan

Relocated from its original position by the Academy of Sciences, the new National Library opened in 2012 and is designed to look like an open book. The biggest library in central Asia, it holds over 10 million books – the original building housed only 2.5 million when it opened, but a call was put out to Tajiks to donate books to help fill the shelves.

On the first floor you can find books about Tajik history, culture and traditions. The library also houses an important collection of ancient manuscripts that includes one of the earliest copies of Firdausi’s famous work, the Shahnama (Book of Kings).

Writers’ Union Building

On the northern side of Ismoili Somoni, this is one of Dushanbe’s most unusual but striking constructions. It dates from the Soviet period but its façade is covered with life-sized statues of Tajik poets and other cultural heroes whose lives and work span the last millennium.

With the notable exception of Firdausi, few of the names are easily recognisable to foreigners, but this monument does show the high esteem in which the Tajik people hold their vernacular literary figures.

Garm Chashma

Some 30km south of Khorog on the road to Ishkashim is the village of Andarob – the turning-off point for Garm Chashma, the best hot springs in Tajikistan. Legend has it that Ali struck the ground with his sword while fighting a dragon, and hot water spewed forth.

The springs, which are surrounded with a vast, cave-like mineral deposit, are reputed to treat 72 different types of illness, the primary ones being dermatological and orthopedic conditions. They are used in turn by men and women; if you arrive during the other sex’s session you can either wait or use the covered (and far less dramatic) side pools.

It is expected that you will bathe naked, and the salts and sulphur leave your skin feeling remarkably soft. At 65°C, it’s recommended to stay in the water for only 10–15 minutes, but we were assured by staff at the pool that the waters are safe for everyone. Prices range from TJS2 to TJS25 depending on when you go and whether you use the VIP pool.

It is possible to stay at the site overnight at the Somon-TM hotel, owned by the president’s daughter. Rooms are all en suite and expensive by Tajik standards (especially outside Dushanbe), but you do get breakfast and a private session at the VIP pool included in the price.

Close to Andarob, a little off the main road, is the Kuh-i Lal (Ruby Mountain) described by Marco Polo. The mine here still produces small quantities of spinels (also known as balas ruby) and you will occasionally be offered uncut stones to buy.

Khujand

One of Tajikistan’s largest and wealthiest cities, Khujand has an almost cosmopolitan air and it bears the weight of its turbulent history well. Parks and monuments have all been sensitively restored, the bazaar is one of the liveliest in central Asia, and the mighty river, Syr Darya (Jaxartes), is a striking urban centrepiece. The well-paved streets, commercial centres and modern airport all reflect the city’s relative prosperity and solid position as an economic engine in the Fergana Valley.

Khujand feels much friendlier and relaxed than Dushanbe, having a compact centre where it’s impossible to escape the smell of its infamous shashlik, and many an hour can be whiled away people watching from the pavement restaurants and cafés.

While its most famous monuments are centuries old, they are starting to be rivalled by newer attractions such as the cable car, opened in 2019, and the increasing number of boat trips being offered down the sparkling clear river.

The best things to see in Khujand

Sheik Muslihiddin Mosque

The fairly modern Sheik Muslihiddin Mosque is the city’s largest place of worship and cuts a striking figure on the skyline: the intricate portico, tiled minaret and turquoise domes would not look out of place in Bukhara or Samarkand. There is an attractive 19th-century minaret made of baked-mud bricks. It stands 21m tall and is a particularly popular resting place for the local pigeon population.

Sheik Muslihiddin (1133–1223) is buried in the 14th-century gilded mausoleum on the same site. He was a holy poet come miracle worker who was revered by local people. Originally buried in the suburbs, his remains were moved here shortly before the Mongol invasion. The mud-brick tomb and its contents were burned by the Mongols and completely destroyed, so the mausoleum you see today dates from two later periods of construction in the 14th and 16th centuries respectively.

Panjshanbe Bazaar

On the opposite side of the square to the mosque is Panjshanbe Bazaar, Khujand’s central market. The vast pink edifice with its attractive white plasterwork and central semi-dome looks as if it should be the set for a fairy-tale wedding or an 18th-century royal ball, but it in fact dates from 1964 and was always intended to house market traders and their wares.

Climbing the stairs to the right of the main entrance enables you to get a closer look at the beautifully painted ceiling, and also offers a good vantage point for photographs across the square. The market itself has a lively atmosphere, particularly in the morning, and you’ll scarcely be able to set foot among the fruit stalls before someone will accost you with a slice of melon or handful of pomegranate seeds to try.

Every kind of good is for sale here, and the hours fly by as you rummage around, engage in riotous charades and buy all sorts of things you never knew you needed. It’s a great place for people watching, and the market traders are friendly, always keen to chat and pose for photographs.

Khujand Fortress

A short distance west of Ismoili Somoni is Victory Square (also called Pushkin Square) and the historic centre of the city: Khujand Fortress. Archaeological excavations on the site have unearthed Graeco- Bactrian coins, pottery shards and other items which date the earliest parts of the citadel to the 4th century bc. Many of these are displayed in the museum.

The fortress was continually rebuilt and expanded for 2,500 years, however, as every time it was attacked, significant reconstruction was required. It reached its greatest extent in the 13th century, with thick clay walls atop an embankment, a water-filled moat, and a city wall encompassing 20ha of land, but even then it was no match for Genghis Khan. The Mongols completely destroyed the fortress.

Cable car

Kamoli Khujand Park is home to one of Khujand’s newest tourist attractions, a cable car taking you on a slow and graceful journey over the Syr Darya, with an optional stop on the north side of the river. VIP carriages offer the opportunity to relax and enjoy the view while sitting on a sofa.

Lake Sarez

Lake Sarez (3,263m) is often referred to as the ‘sleeping dragon’, and it is easy to see why. It was formed by an earthquake in February 1911 estimated to be between 6.5 and 7.0 on the Richter scale, as the resulting landslide shifted over 2 billion m³ of rock and formed the Usoi Dam. At approximately 5km long, 3.2km wide and up to 567m high, it is the tallest natural dam in the world.

Named after the village buried by the landslide, it killed an estimated 302 people. The isolation and destruction of the mountain tracks was such that word did not reach the Russian posts at Murgob and Khorog about the earthquake for six weeks.

Following a landslide that caused a 2m-high wave in the lake in 1968, investigations were held into the stability of the dam. The primary danger is thought to be a partially detached section of rock around 3km³ in size which could break loose and fall into the lake. Owing to the narrowness of the valley below, a flood would be highly destructive.

Initially, a 50m-tall wave of water travelling at 300km/h would destroy all of the villages in the Bartang Valley. Within 10 hours, the wall of water would flood the flat parts of south Tajikistan before dividing into two large rivers which move on to Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, finally reaching the Aral Sea. In total, it is thought the flood could affect over 5 million people, 370,000 of whom are from Tajikistan.

Trekking routes

Treks focused on Lake Sarez start in Barchidev, the last settlement where you’ll find a homestay. The first day of the trek takes you south along the Murgob River and to the vast, natural dam at Usoi, the village now buried beneath the rockfall. It is possible to turn from here to Barchidev if you only have time for a short trek, though most people prefer to continue round the lake to Irkht. There are two variations to this part of the route: a boat trip across the water, or the strenuous and vertigo-inducing climb over the Marjanai Pass (3,972m).

Irkht was once a meteorological station, but little indication of this now remains. It’s another day’s hard walk up the Langar River to Vykhinch and thence the three head-like lakes at Uchkul. There is another steep climb, this time to the Langar–Kutal Pass (4,630m), from where it is 20km to the summer pastures at Langar (not to be confused with Langar in the Wakhan Corridor). You’ll be welcomed with bread and tea, and possibly fresh ewes’ milk too.

Langar lies just below Jasilkul, one of the four largest lakes in the Pamirs. The final leg of the trek winds its way down the river valley to Bachchor at the northeastern end of the Gunt Valley. The path rejoins the road at Bachchor, whence it is 22km back to the Pamir Highway or 116km to Khorog. We would advise driving.

To complete this trek you will need detailed topographical maps of the area. The best currently available ones are those produced by the Soviet military, and thankfully the topography of the area has changed little since they were drawn up. You can download the complete set from Mapstor. They go down to 1:50,000 scale.

Maps are no substitute for a competent guide who knows the local area and can read the conditions on the mountains. You should contact PECTA or Pamir Silk Travel, both of which are in Khorog, to get a reliable recommendation.

Panjakent

Ideally located only a short drive from the Uzbek border, with its historical sites and bustling bazaar, Panjakent (often spelled Penjikent) strongly deserves to be more than just an overnight stop en route between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Long the gateway between the two countries, it should probably be part of Uzbekistan given that 70% of the population is ethnically Uzbek. The superb archaeological sites of ancient Panjakent and nearby Sarazm have earned it the moniker ‘the Pompeii of central Asia’ and are potent reminders of its historical importance and erstwhile wealth

Ancient Panjakent

Ancient Panjakent is remarkable due to the state of its preservation. Having been abandoned suddenly and never built over, it is still possible to walk the streets laid out much the same way as they were the day the Arabs came. At its height in the 8th century, the city covered around 20ha, and about half of this area has been carefully excavated, with finds being removed to the National Museum in Dushanbe and the local Rudaki Museum. Most impressive among the buildings are the citadel on top of the hill overlooking the city, the necropolis, and the fine, once multi-storied buildings where the famous frescoes were discovered.

There is a small museum near the entrance to the ruins, featuring a handful of artefacts and detailed information about the life of Russian archaeologist Boris Marshak, who spent half a century excavating the site and lobbying for its preservation. As per his will, Marshak is buried on the grounds.

Taxis can be hired to visit the ruins, which overlook the modern city a mere 2km south of Rudaki, adjacent the airport. The labyrinthine ruins are open around the clock, but it is advisable to visit only within the operating hours of the museum.

Sarazm

Some 15km west of Panjakent, just before the newly reopened Uzbek border, are the impressive ruins of one of Tajikistan’s other great archaeological sites: Sarazm. Discovered in 1976 by the Soviet archaeologist Abdullojon Isakov, it is remarkable for both its size and its antiquity.

Sarazm is an open-air site so there are no fixed opening times, and no entrance fee. Local people may appear to ‘guide’ you around the site, in which case give them a small donation for their time. There is very little information on the site itself aside from a few weathered information boards, so it’s a place you can let your imagination wander.

The earthen mounds and depressions on the site were once urban structures, burial sites and reservoirs, and a visit to Sarazm is a nod to the long human history of Tajikistan. Known by archaeologists as a ‘proto-urban site’ because of its status as one of the world’s oldest cities, the Sarazm settlement originally spread across 130ha.

It was the first settlement in central Asia to form such far-reaching trading connections and have such a vibrant cultural heritage. Carbon dating confirms it was already inhabited by 3500BC, peaking at the start of the Bronze Age when it was likely the largest metallurgical centre in central Asia. It thrived until the 3rd millennium BC and was added to UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites in 2010 (the first UNESCO site in Tajikistan) in recognition of its historical significance in being the physical and cultural meeting point of settled farming tribes and the nomads of the Eurasian steppe.

The name ‘Sarazm’ means ‘where the land begins’, and for several millennia the settlement served as a great centre of trade and industry, producing handicrafts, tools and other artefacts that were sold and utilised throughout the ancient world.

The Pamir Highway

The prize for the world’s best drive is hotly contested, but the Pamir Highway certainly comes close to perfection (at least in terms of thrills and views). Magnificent mountains, gushing rivers and waterfalls, summer settlements with nomads and sheep, and scarcely another vehicle in sight are all points in its favour.

While it’s not a route for the faint-hearted, if you have the physical and mental stamina it’s a once in a lifetime experience whether you’re travelling by two wheels or four. Be sure to visit in the summer months as the road is impassable during the rest of the year.

Whether you choose to take the southern route through the southwest of Tajikistan, or the harder, more rugged route through the central part of the country, either way you end up in laid-back Khorog, the backpackers’ hub in the Pamirs. From here it’s a challenging drive south to the Afghan border, then on to the windswept wasteland of the Murgob Plateau.

Khorog to Murgob

The eastern section of the Pamir Highway between Khorog and Osh, Kyrgyzstan, was built by Soviet military engineers in the early 1930s. Its construction was a phenomenal achievement. It is the second-highest international road in the world (after the Khujerab Pass between Pakistan and China), and primary construction took just three years.

It was significantly upgraded to allow improved military access for the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, as this was one of the most important routes for the ill-fated campaign. However, the road appears to have received little love and attention since, and this is a challenging route requiring a sturdy vehicle and a lot of patience.

If using apps to map your route, expect the journey to take considerably longer than the estimated duration, and take your time – the views are beautiful, and the odd memorial is a stark reminder that it is more important to reach your destination safe, albeit a little later than planned.

Murgob to the Kyrgyz border

The final stretch of the Pamir Highway heads north from Murgob to Bor Dobo, just across the Tajik–Kyrgyz border, and thence to Sary Tash and Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second city. This northern part of the Pamirs is the remotest part of Tajikistan, and also home to some of the finest trekking routes (and rarest wildlife) in the country.

Strangely, the quality of the roads seems to improve, and the final stretch of the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan takes you past more jagged peaks and turquoise lakes.

As you near the Kyrgyz border, you’ll also see a short fence on your right – this understated feature is the border with China.

Yagnob Valley

The word Yagnob (or Yaghnob) is thought to be derived from the Tajik adaptation of the Yagnobi phrase ‘ix-I nou’, meaning ‘ice valley’ or ‘ice river’. Until the Russians blasted the road through the mountains, the Yagnob Valley was almost entirely cut off from the outside world, accessible only on foot when the weather would allow. It remains one of Tajikistan’s most wild, unspoilt spots and a fascinating anthropological microcosm.

The valley’s singularity of language, traditions and landscape was first noticed by Europeans in the late 19th century, but the inhabitants of the region themselves consider their ancestral line to go back some 2,500 years into the past, to the era of the ancient Sogdiana civilisation.

At almost 3,000m above sea level, the valley houses a mere 500 people during the winter months spread among some ten small settlements, though this swells to around 3,000 in the summer. The low population is due mostly to forced resettlement of the villagers to cotton-growing regions by the Soviets in the mid 20th century. The Yagnobis’ stone houses are typically clustered in the relatively wide areas along the Yagnob River, surrounded by spectacular mountain peaks and incredible trekking trails.

Tajikistan is a paradise for nature lovers and those who spend time in the great outdoors, and this is never more true than in the Yagnob Valley. Zamin Karor (the Yagnob Wall, which translates as ‘quiet ground’) can be found in the Yagnob Valley. The dramatic cliffs can be seen for miles around and are often home to climbing competitions. There are eight distinct peaks with altitudes ranging from 3,709m to 4,767m, with western and northwestern walls providing the most complex mountaineering routes.

The valley is also home to striking petrified forests dating back to the Jurassic period, when the region was much more humid and fertile. The ferrous vines and hardened tree trunks stand up to 5m high, a reminder of the valley’s timelessness and the resilience of nature.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Tajikistan:

Related articles

From boiling lakes to vast alpine bodies of water, these are our favourite lakes from around the world.

Discover our favourite sights along one of the most important trading routes in history.

Exploring one of our favourite regions with our Photographer of the Month, Cynthia Bil.

Tajikistan’s tourism industry is taking on a new focus, one that brings its breathtaking landscapes to life through a millennia of history.

If you are serious about the challenge, then the chance to see things at your own pace and to meet Pamiris will be among the greatest rewards of cycling.

Never mind the Premier League; this is the weekend’s real entertainment.

The Fann Mountains are a veritable adventure playground for climbers and trekkers alike.