A region of strange rock formations and painted cave churches, Cappadocia is one of Turkey’s most visited and photographed sites – and you can see why. While UNESCO-listed Göreme is the most famous collection of rock churches, the wild fairy-cone landscapes of Cappadocia are in themselves a highlight, along with many other lesser-known valleys like Ihlara and Soğnali, not to mention the extraordinary underground cities.

September and October are some of the best months to visit Cappadocia – it is not too hot, and you have the added benefit of the glorious autumn colours.

Göreme

You’ll need at least three days to explore the area in full. We suggest basing yourself in Göreme – now an open-air museum, it is the the undisputed highpoint of the Cappadocia region, thanks to the quality of its cave churches and their internal frescoes. Allow a good two hours to walk round its nine churches, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and accessible on foot from the centre of town.

However, the loveliest of Göreme churches is not even inside the open-air museum: it lies apart, on the opposite side of the road from the car park, back down the hill about 75m. If you can only visit one church in all Cappadocia, you should make it Tokalı Kilise. The biggest and most interesting of the Göreme churches, the name Tokalı means ‘Buckle’, from a buckle which once adorned the ceiling, now vanished. Inside it is magnificent. It is a complex of two churches, built 100 years apart. We won’t spoil the surprise – go see it for yourself.

During your in Göreme, be sure to book a table at Dibek and order your slow-cooked testi kepap (pottery kebab) 24 hours in advance.

For those with a head for heights, organise a sunrise hot-air balloon ride with one of the many tour operators situated along the village’s main street. If you’d rather keep your feet firmly on the ground, make the effort to get up for sunrise, wrap up warm and head out to watch the hot-air balloons drift slowly across the village and the surrounding valleys – a remarkable sight.

Üçhisar

Spend a morning or an afternoon at this once-scruffy village, cut into the region’s tallest fairy chimney and home to a number of spectacular cave hotels.

A path signposted ‘kale’ leads through the houses and climbs right to the top of the citadel cone, at 1,350m, where there is an impressive view of the whole Göreme Valley. At night it is illuminated, looking like some colossal hollowed-out gourd for Halloween.

Zelve Valley

Perhaps then head to the Zelve Valley, one of the most enjoyable areas of Cappadocia to explore on foot and home to troglodyte dwellings dug out of three pretty valleys. Although much frequented by tours, it generally only takes 20 minutes to go to the main part and then return, leaving the best parts of the valley untouched; it takes at least an hour for even an energetic individual to do the circuit of the three valleys.

Avanos

Avanos (altitude: 926m) is a pretty town on the banks of the Red River, the Kızılırmak, the longest river in Anatolia. The distinctive deep-red soil which colours the water is much in evidence all around and on a rainy day you and your mode of transport will soon be covered in it.

The famous pottery is made from this local clay, exported from earliest times to Greece and Rome, and you can visit the pottery workshops in the centre of town near the PTT office. Most people come to sit on the riverbank and sip tea or eat ice cream, while watching the Venetian-style gondolas slide to and fro.

The underground cities

Cappadocia is home to three remarkable underground cave cities: Özkonak, Kaymaklı and Derinkuyu. Each boasts elaborate networks of tunnels, stairways and chambers hollowed out of the rock, never so low that you cannot stand up, but rarely spacious and certainly not for the claustrophobic.

Derinkuyu is the biggest and deepest (and therefore the most popular), while Özkonak is quietest due to its off-the-beaten-track location. We’d recommend a trip to Kaymaklı, about 9km north of Derinkuyu and easily accessible on a half-day trip.

Soğanlı Valley

To escape the crowds of downtown Cappadocia, a pleasant excursion is to the Soğanlı Valley. In a half-day it can also be combined with a round trip to Derinkuyu and Kaymaklı underground cities.

The overall setting of Soğanlı is far more attractive both as a village and as a valley than the more famous Göreme. It is closer to the original setting and is still unspoilt by the mushrooming hotels and billboards that mar the landscapes of the Cappadocian heartlands. There are some 60 churches in all in the Soğanlı Valley, but many are filled up with earth or have been turned into pigeon-cotes by the villagers.

Ilhara Gorge

Independent travellers will want to explore the splendid 16km-long Ihlara Gorge, formerly called the Peristrema Valley by the Greeks. The trip can take a full afternoon, or an entire day if you want to do some extra walking.

The 150m-deep canyon was formed thousands of years ago by erosion from the Melendiz River, flowing north into the Tuz Gölü (the Great Salt Lake). The river is the product of melting snow from the Hasan Daği Volcano and the Melendiz Mountains.

The major churches are indicated by signs, but it is fun to go a little further afield to the more distant churches, as walking along the canyon bed is extremely pleasant with the sound of the rushing river and the wind in the tall poplar trees. Wildlife is abundant, with birds, frogs and lizards, and there are far more butterflies to be seen here than almost anywhere east of Ankara, including blues, large coppers and painted ladies. After the bleak and featureless wastelands of the plateau this is indeed a sight to behold.

More information

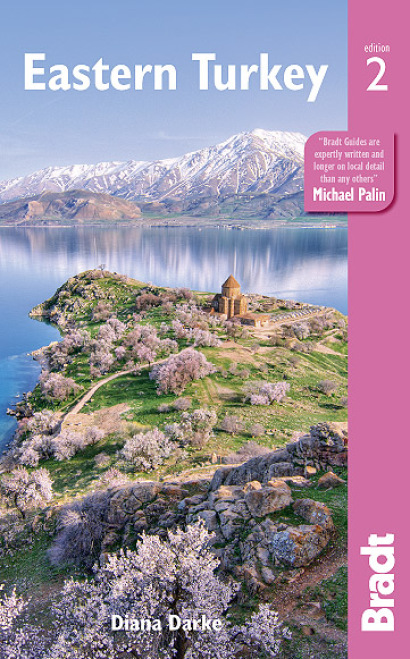

Inspired to start planning a trip? Make sure you take our Eastern Turkey guide with you: