As things stand, it is not the least of Mozambique’s attractions that it still offers ample scope for genuinely exploratory travel, offering adventurous travellers the opportunity to experience it entirely for themselves.

Philip Briggs, author of Mozambique: the Bradt Guide

Visit Mozambique today, and you’ll find it difficult to imagine that it once attracted a larger number of tourists than South Africa and Rhodesia (covered by present-day Zimbabwe). Equally incredible, for that matter, is the realisation that, over the 15 years prior to 1992, this beguiling country was embroiled in an all-consuming civil war that claimed the lives of almost a million people, and caused the displacement of five times more.

Fortunately, the civil war is long over, and Mozambique is celebrating over 25 years of relative political stability, economic growth and progressive governance. The simmering conflict with Islamist insurgents in the northeast notwithstanding, one of the most notable things when talking to Mozambicans about their recent history is how much more interested they are in making the most of the future rather than sliding back into the arguments of the past.

Over the last couple of decades, Mozambique has been one of Africa’s rising stars as far as developing tourism is concerned. True, this trend is to some extent reflective of the tiny base from which tourism has grown since the early 1990s. Equally, during South African and Zimbabwean school vacations, the resorts that line the coast between Maputo and Beira are bursting with cross-border holidaymakers, to the extent that in some resorts you’ll hear more English and Afrikaans spoken than Portuguese or any indigenous language.

So far as tourists are concerned, Mozambique might just as well be two countries. Linked only by a solitary bridge that spans the mighty Zambezi River at Caia, and divided by the more than 1,000km of road connecting Beira and Nampula, southern Mozambique and northern Mozambique offer entirely different experiences to visitors. The two parts of the country have in common the widespread use of Portuguese and a quite startlingly beautiful coastline.

The difference is that the south coast of Mozambique is already established as a tourist destination, with rapidly improving facilities and a ready-made market in the form of its eastern neighbours. The north, by contrast, has fewer facilities for tourists, and getting to those that do exist takes determination and either time or money – although once you reach them they are the equal of anything in the region, and in some cases the world.

Mozambique may not be the easiest country in which to travel; in more remote regions it can be downright frustrating. But this is changing and for the better. As things stand, it is not the least of Mozambique’s attractions that it still offers ample scope for genuinely exploratory travel, offering adventurous travellers the opportunity to experience it entirely for themselves, without the distorting medium of a developed tourist industry.

For more information, check out our guide to Mozambique:

Food and drink in Mozambique

Food

Mozambique’s lack of infrastructure and general easy-going attitude mean that restaurants tend to adopt a rather laissez-faire attitude towards menus, service and opening hours. The further you are from the city centres, the more flexible you’ll need to be. As a very general guideline, the more Westernised restaurants in the biggest cities (Maputo, Beira and to a lesser extent Nampula) will be open from around 10.00 to 20.00/21.00 and will have most of their menus available.

In remote rural areas, food will by and large be limited to ncima and meat, chicken, fish, beans or similar. Meat (if you’re offered it) will be goat – beef is very rarely available outside the major towns, unless you are (for whatever reason) an honoured guest.

Ncima (which is also known as ugi, ugali, sadza or pap) is a form of porridge made by mixing ground maize with water and boiling it until it forms a starchy paste. It can then either be eaten as a hot porridge or left to set and eaten cold in chunks. Many foreigners are indifferent to the stodgy result, but Africans by and large love it – so much so that if offered a choice between ncima and a more Western staple such as potatoes or rice, they will choose the ncima.

In the bigger towns, menus tend to be either chips or rice with a side salad (usually heavy on tomatoes and onions) and fish (or some other form of seafood), chicken or beef. Chicken and fish will tend to be grilled or fried, while beef will almost always be a variant on a Portuguese dish called a prego. A prego is essentially a minute steak, usually boiled with a sauce that tastes a little like a toned-down Worcestershire sauce. The classic prego no prato (literally ‘prego on a plate’) will be served with a portion of rice, a portion of chips, the side salad and a fried egg on top.

A common snack is the prego no pão, a prego in a bread roll. Many of the dishes that you’ll see in the swankier restaurants will be variants on the prego no prato, sometimes with added ingredients (chouriço sausage, for instance). Given the length of the coastline, it would be surprising if the Mozambican seafood wasn’t outstanding, and Mozambican prawns do indeed have a global reputation, but the crab, lobster, crayfish and octopus are equally good.

Drink

Coca-Cola is the undisputed champion of the cola wars in Mozambique, being available virtually everywhere across the country, along with various flavours of Fanta (its stablemate). Sparletta, another range of soft drinks produced by Coca-Cola, is also universally available – the lemon-twist flavour is quite refreshing. They will almost always be brought to you sealed and opened in front of you. You can buy fruit juices in the Shoprite supermarkets, and you should be able to get the mixed fruit juice called Santal in most of the larger towns. Bottled water is ubiquitous but again make sure it’s sealed.

The most widespread beers are 2M (named after a former French president called Mac-Mahon), Laurentina (which comes in three styles: two Continental-style lagers and a stout), and Manica. You can also get South African brands such as Castle and Savanna cider.

Wine is imported, mostly from South Africa but also from Portugal. You can get it in bottles as normal, or in larger outlets (if you’re willing to risk it) in five-litre containers with a plastic raffia-style handle. The wine in the latter is undoubtedly an acquired taste.

The locally made Tipo Tinto rum (with the rather incongruous parasol-wielding geisha on the label) is something of a cult favourite in the southern beachside towns, particularly when mixed with raspberry Sparletta to make an R&R (rum and raspberry).

Health and safety in Mozambique

Health

In Mozambique there are private clinics, hospitals and pharmacies in most large towns, but unless you speak Portuguese you may have difficulty communicating your needs beyond relatively straightforward requests such as a malaria test – try to find somebody bilingual to visit the hospital with you.

Consultation fees and laboratory tests are remarkably inexpensive when compared with those in Western countries so, if you do fall ill, it would be absurd to let financial considerations dissuade you from seeking medical help.

You should be able to buy such commonly required medicines as broad-spectrum antibiotics and metronidazole (Flagyl) in any sizeable town. If you are wandering off the beaten track, it might be worth carrying the obvious with you. As for malaria tablets, whether for prophylaxis or treatment, you would be wise to get them before you go as not all tablets are available readily.

Preparations

Sensible preparation will go a long way to ensuring your trip goes smoothly. Particularly for first-time visitors to Africa, this includes a visit to a travel clinic at least eight weeks in advance of your trip to discuss matters such as vaccinations and malaria prevention.

- Don’t travel without good quality, comprehensive medical travel insurance that covers the activities you intend to pursue, is adequate for your health needs and will fly you home in an emergency.

- Make sure all your routine vaccine courses and boosters are up to date. In the UK this includes measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and diphtheria, tetanus and polio (DTP). Proof of vaccination against yellow fever is needed for entry into Mozambique for everyone aged one and above if you are coming from a yellow fever endemic area including if you have a transit time of 12 hours or more.

- Most travellers will be advised to be vaccinated against typhoid and hepatitis A. Vaccination against hepatitis B and rabies may also be recommended. Cholera vaccine is usually only recommended during outbreaks and if there is little or no guarantee of clean water.

- The biggest health threat is malaria. There is no vaccine against this mosquito-borne disease, but a variety of preventative drugs is available, including atovaquone/progunail (Malarone), doxycycline and sometimes mefloquine (Lariam). The most suitable choice of drug varies depending on the individual and the country they are visiting, so visit your GP or a travel clinic for medical advice.

Safety

Theft and violence

Bearing in mind that no country in the world is totally free of crime, and that tourists to so-called developing nations are always conspicuously wealthy targets, Mozambique is a relatively low-risk country so far as crime is concerned. Compared with parts of Kenya and South Africa, mugging is rare and the sort of con tricks that abound in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam even rarer.

Petty theft such as pickpocketing and bag-snatching can be a risk in busy markets and other crowded places, but on a scale that should prompt caution rather than paranoia. Walking around large towns at night feels safe enough, though it would be tempting fate to wander alone along unlit streets or to carry large sums of money or valuables.

Female travellers

Women travellers generally regard subequatorial Africa as one of the safest places to travel alone anywhere in the world. Mozambique in particular poses few if any risks specific to female travellers.

It is reasonable to expect a fair bit of flirting and the odd direct proposition, especially if you mingle in local bars, but a firm ‘no’ should be enough to defuse any potential situation. To be fair to Mozambican men, you can expect the same sort of thing in any country, and – probably with a far greater degree of persistence – from many male travellers.

Perhaps as a result of Frelimo’s feminist leanings, Mozambican women tend to dress and behave far less conservatively than their counterparts in neighbouring countries. You will often see evidently ‘respectable’ women drinking in bars and smoking on the street, behaviour that is seen as the preserve of males and prostitutes in many other parts of East and southern Africa.

As for dress codes, Muslims in Mozambique seem far less orthodox than in some other African countries, but overly revealing clothes will undoubtedly attract the attention of males.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Unlike some of its neighbouring African countries, homosexuality is legal in Mozambique. As of June 2015, Mozambique became the 12th African country to decriminalise homosexuality, although same-sex marriages are not recognised.

As such, while it is legal, that isn’t to say that the overall attitude towards homosexuality has changed, but travellers are unlikely to encounter any problems. The Mozambique Association for Sexual Minority Rights has been active in the country (albeit unregistered) since 2006. For more information and details of social events, visit their Facebook page.

Travel and visas in Mozambique

Visas

A valid passport is required to enter Mozambique. The date of expiry should be at least six months after you intend to end your travels; if it is likely to expire before that, get a new passport.

South Africans

If you are travelling on a South African passport (or one from another neighbouring country), you no longer need a visa to enter Mozambique: when you arrive at the border, you will be given a free entry permit valid for up to 30 days. However, these permits cannot be extended in Mozambique itself. If you intend on staying longer, then either you will need to get a single-entry visa valid for the required period in advance, or you must leave and re-enter Mozambique before that month expires.

All other nationalities

Visas are required by everyone else and individual visitors are allotted a maximum of 90 days per year on a tourist visa. It is possible to purchase a 30-day, single-entry tourist visa upon arrival at 44 border crossings (the remaining 14 borders are the least crossed and are expected to have the capability to issue visas upon arrival in the near future), including international airports. The cost per visa is Mt2,000 (approx US$40), but, if you lack local currency, you could be charged as much as US$80.

The visa can be extended in-country up to two times for an additional 30 days (making 90 days in total) at any of the immigration offices that are located in all provincial capitals. By contrast, purchasing a 90-day multi-entry visa in advance may require you to cross a border in and out of the country every 30 days.

Although each office tends to have its own flow rate, extensions typically require at least a week for processing, so be sure to submit your passport for extensions two to three business days prior to the visa’s expiration and plan on picking it up a week from submission.

Getting there and away

By air

The only airlines with direct flights to/from Europe are TAP Air Portugal and, in a new service since 2020, the Mozambican national carrier, LAM, both of which route through Lisbon. Another reasonably direct option from certain European cities, including London, is Ethiopian Airlines, routing through Addis Ababa, or Kenya Airways, routing through Nairobi.

It is more common for European and other intercontinental visitors to fly to Johannesburg (South Africa) and transfer to Mozambique from there, and Qatar Airways now flies from Doha to Maputo. South African Airways operate plenty of flights daily between Johannesburg and Maputo, and the former also flies from Maputo to all provincial capitals in Mozambique.

SAA also flies direct to Maputo from Durban, as well as directly from Johannesburg to Vilankulo, Beira, Tete, Nampula and Pemba in partnership with Airlink. A new international airport, Filipe Jacinto Nyusi Airport, has been built in Chongoene, near Xai-Xai. Opened at the end of 2021, the airport is currently served by LAM, operating flights from Maputo and Johannesburg.

By land

Provided you arrive at the border with a visa, you should have no problem entering Mozambique overland, nor is there a serious likelihood of being asked about onward tickets, funds or vaccination certificates. About the worst you can expect at customs is a cursory search of your luggage.

Tours2moz runs a shuttle service from South Africa, starting from Johannesburg or Pretoria and going to various destinations (including hotels and hostels) in Mozambique, from Ponta do Ouro to Maputo and up the coast to Xai-Xai, Tofo, Barra, Inhambane and Vilankulo.

Getting around

By air

Given Mozambique’s size, and the variable conditions of some of the roads, internal flights can be an attractive option. The provincial capitals all have their own airports and most have regular scheduled flights. Prices tend to be high, however, a situation that dates back to when the national airline, LAM, had a monopoly on internal flights. This is beginning to change, and you can often pick up (relatively) competitive flight prices on their website.

By boat

There are regular ferries between Maputo, Katembe and Inhaca, as well as between Maxixe and Inhambane. Boats must also be used to get between Vilankulo or Inhassoro and the islands of the Bazaruto Archipelago, to Ibo Island in northern Mozambique, and to cross some of the country’s main rivers and inland waterways (the Zambezi River, Ruvuma River and Lago Niassa, for instance).

If travelling by sea is your thing, you may be able to find the odd trawler plying the coast between Beira and Quelimane, or the occasional supply boat to coastal villages south of Beira; in the far north near the Tanzanian border, private fishing dhows are a legitimate alternative to travelling by road.

By rail

There are only four passenger routes that would interest travellers: between Maputo and the South African border at Ressano Garcia; between Nampula and Cuamba; between Cuamba and Lichinga; and to/from Maputo and the Zimbabwean border at Chicualacuala (Vila Eduardo Mondlane). The rest of the network, though marked on the maps, is either out of action or only used for freight trains and, while you may be able to hitch a lift on one, travelling by road will be quicker and easier.

When to visit Mozambique

Climate

The coastal regions of Mozambique are best visited in the dry winter months of May through to October, when daytime temperatures are generally around 20–25°C.

There is no major obstacle to visiting Mozambique during the summer months of November to April, except that climatic conditions are oppressively hot and humid at this time of year, especially along the north coast. Because most of the country’s rain falls during the summer months, there is also an increased risk of contracting malaria and of dirt roads being washed out.

Public holidays and festivals

Unless you are a South African with children at school, it is emphatically worth avoiding the south coast of Mozambique during South African school holidays, when campsites as far north as Vilankulo tend to be very crowded and hotels are often fully booked.

The exact dates of South African school holidays vary slightly on a provincial basis, but the main ones to avoid are those for Gauteng (the province that includes Johannesburg, South Africa’s most populous city and only a day’s drive from Maputo).

To give a rough idea of the periods to avoid, there are four annual school holidays in Gauteng: a three-week holiday that starts in the last week of March and ends in the middle of April, a month-long holiday running from late June to late July, a two-week holiday starting in late September, and a six-week holiday from early December to mid-January. If you do visit southern Mozambique during school holidays, then you should make reservations for all the hotels and campsites at which you plan to stay.

In addition to the fixed public holidays listed below, Good Friday and Easter Monday are recognised as public holidays in Mozambique. Other Islamic and Christian religious holidays are widely observed as well. Many of these days will be marked by heavily orchestrated public demonstrations and marches.

There are also marked commemorative days and, in addition, most larger cities have their own public holiday; Maputo’s is on 10 November.

- 1 January – New Year’s Day

- 3 February – Heroes’ Day

- 7 April – Women’s Day

- 1 May – Labour Day

- 25 June – National Day (Independence Day)

- 7 September – Lusaka Accord Day

- 25 September – Armed Forces Day

- 4 October – Peace and National Reconciliation Day (end of Civil War)

- 25 December – Family Day

Itineraries

If you want to view and compare sample itineraries, please see the Mozambique holidays section on SafariBookings. This comparison website lists tours offered by both local and international tour operators.

What to see and do in Mozambique

Bazaruto National Park

Comprising a string of small sandy islands lying roughly 14–25km from the mainland north of Vilankulo and south of Inhassoro, the Bazaruto Archipelago was one of the few parts of Mozambique that remained safe to visit during the closing years of the civil war, when it developed as an upmarket package-based tourist destination that functioned in near isolation from the rest of the country.

That much is arguably still true today, since all the archipelago’s lodges slot comfortably into the upmarket or exclusive price bracket, and their fly-in clientele consists mostly of people on a multi-country itinerary who barely set foot on the Mozambican mainland.

That said, Bazaruto is also the focal point of marine activities out of Vilankulo and Inhassoro, and its islands and reefs are the target of almost all diving, snorkelling and other day excursions from these popular mainland resorts. In 1971, the archipelago’s five main islands and the surrounding ocean were gazetted as Bazaruto National Park, which extends eastward from the coastline between Vilankulo and Inhassoro to cover some 1,430km².

The three largest islands were formerly part of a peninsula that is thought to have separated from the mainland within the last 10,000 years. The largest and most northerly island is Bazaruto itself: 30km long, on average 5km wide, and punctuated by a few substantial freshwater lakes near its southern tip. South of this, Benguerra, the second-largest island at 11km long by 5.5km wide, was known to the Portuguese as Santa Antonio, but was later renamed after an important local chief.

South of this, the much smaller Magaruque lies almost directly opposite Vilankulo. The smallest island, Santa Carolina, also known as Paradise Island, is a former penal colony covering an area of about 2km² roughly halfway between Bazaruto and the mainland near Inhassoro. The fifth island, Bangue, is only rarely visited by tourists.

Diving and snorkelling

There are numerous dive sites dotted around the islands, but the undisputed champion is Two Mile Reef, a barrier reef that lies on the outer side of the archipelago between the islands of Bazaruto and Benguerra. Tides permitting, the best snorkelling spot is The Aquarium, a calm coral garden that lies on the inner reef and supports a dazzling selection of hard and soft corals, as well as reef fish of all shapes and colours, from tiny coral fish to the mighty potato bass and brindle bass. It is also a good spot to see reef sharks and marine turtles, though neither is guaranteed, while lucky divers might see manta rays and whale sharks.

There are a host of dive sites on the seaward side of the same reef, with evocative names such as The Arches, Shark Point, Surgeon Rock, The Cathedral and The Gap. Any dive centre can advise on the site most suitable to your interests and current conditions but, if you are setting up a trip from Vilankulo, it is emphatically worth paying the extra to visit Two Mile Reef as opposed to taking the cheaper excursion of Magaruque, which has no proper reefs and thus offers vastly inferior diving and snorkelling.

Pansy Island

Not so much an island as a tidal sandbar situated a short distance south of Bazaruto Island, this popular landmark can easily be visited as an extension of a trip to Two Mile Reef. It is named for the so-called pansy shells (also known as sea biscuits or sand dollars) that are abundant in its intertidal shallows. This pretty shell-like object, with a distinctive five-petalled floral pattern on its flattened face, is not a shell at all, but the endoskeleton of a burrowing sea urchin of the order Clypeasteroida. The living creature is usually black or purple in colour, and covered in bristles, but after it dies the endoskeleton is bleached white by the sun and saline water.

The five petals are formed by a series of perforated pores through which the podia project from the body, and reflect the fivefold radial symmetry associated with all sea urchins. There are also 2cm slits above the floral pattern, the relicts of two grooves used for feeding. Any experienced guide will be able to find you examples of the pansy shell here, as well – with luck – as the living urchin.

Bazaruto Island

A striking feature of the archipelago’s largest island is the immense dunes that rise from its southern shore, and these too can easily be visited in conjunction with Two Mile Reef and Pansy Island. Reputedly the highest point on the islands, rising around 100m above the surrounding water, the steep dunes can be climbed, albeit in something of a two steps forward, one step back mode, and with some serious sandblasting in windy weather.

Once at the top, the view in all directions is utterly exhilarating, with the open ocean and other islands stretching away to the south, and a landscape of lakes and dunes running to the north. If you are staying at one of the lodges on Bazaruto, island tours can be arranged to visit some of the lakes and other dune fields, some of which are spectacular, and to meet local communities.

Benguerra Island

Like its larger and more northerly neighbour, Benguerra supports an attractive and varied landscape of marshes, lakes and tall climbable dunes, well worth exploring on a guided drive if you are staying at one of the lodges.

Wildlife includes plentiful monkeys, small antelope such as red duiker and suni, some impressive crocodiles on the lakes, and a superb mix of birds, with brown-headed parrot, African hoopoe, green pigeon, crowned hornbill and various bee-eaters conspicuous, while flamingos and other waterbirds frequent the lakes. Community visits can also be arranged.

Ilha de Moçambique

The town of Moçambique, which occupies the small offshore coral island of the same name in Mossuril Bay, is the oldest European settlement on the east coast of Africa, and also perhaps the most intriguing and bizarre.

Measuring about 3km from north to south and at no point more than 600m wide, crescent-shaped Ilha de Moçambique (Mozambique Island) was the effective capital of Portuguese East Africa and the most important Indian Ocean port south of Mombasa for almost four centuries.

It houses several of the southern hemisphere’s oldest extant buildings, including the Fortaleza de São Sebastião, the former Convent of São Paulo and a trio of handsome churches. In 1991, the entire island was inscribed as Mozambique’s first (and thus far only) UNESCO World Heritage Site, in recognition of its numerous old buildings and singular architectural cohesion, and it surely ranks as the country’s most alluring urban destination for travellers.

The overall feel of Ilha de Moçambique remains isolated, old-world and not too touristy. Indeed, from that perspective, there may never be a better time to visit the island, poised as it is at a most appealing point along the trajectory between the backwater it had become at the end of the civil war, and the fully developed tourist hub – a kind of southern African counterpart to Zanzibar – that it seems to be heading towards becoming in the not-too-distant future.

Fortaleza de São Sebastião

Dominating the northern tip of the island, the Fortaleza de São Sebastião (Fortress of Saint Sebastian) is arguably the most formidable edifice of its type in Africa. Measuring up to 20m high, it was built of dressed limestone shipped from Lisbon between 1546 and 1583 as a response to the Turkish threat of 1538–53. The shape of the fort has changed little over the intervening centuries, though all but one of the three original entrances, the impressive extant gate beneath the buttress of Santa Barbara, were walled up before 1607.

The fort remains in remarkably good condition, and its wells are still the only source of fresh water on the island. The roof is the best example on the island of the rainwater collection system that sends water flowing into the cisterns. Protected within the fortress, the Capela da Nossa Senhora do Baluarte (Chapel of Our Lady of the Ramparts) is the island’s only other 16th-century building to have survived to the present day.

Within the fortress walls, a new museum, the Museum of Maritime History, is now open. You need to ask when paying the entrance fee to the Palace Museum, and they’ll take you through. The first exhibition is to bring to light the evidence that Ilha was trading with Asia in the millennium before the Europeans arrived.

The museum is the result of a collaboration between UNESCO, The Smithsonian Institute and Mozambique’s Eduardo Mondlane University as part of the Slave Wrecks Project, which aims to uncover and humanise the history of the global slave trade.

Palace of São Paulo

When the Dutch evacuated Ilha de Moçambique in 1607, they burned the old town to the ground, destroying the Muslim quarter as well as two churches and the hospital, and sparing only the Portuguese-held fortress of São Sebastião and the church that is protected within its walls. In 1671, the Omani Arabs again razed much of the old town following their short-lived occupation of the island, for which reason the only extant 17th-century building in the old town is the former Jesuit College of São Paulo.

Today, the former palace is a museum and a fascinating place to explore. The original church, which was formally opened in 1640, is worth looking at for its garish pulpit, a cylindrical wooden protrusion decorated with some beautiful carvings of the Apostles, below which is a chaotic assemblage of rather less lovable but arguably more compelling creatures, a mixture of gargoyles, angels and dragons.

Also notable are the copper-plate altar and the dozen or so religious paintings that decorate the otherwise bare walls. The courtyard separating the church and the palace also has several large statues, for some reason painted in a rather fetching shade of green.

Museo de Marinho

Formerly the Naval Museum but reopened under a new name in August 2009, the Maritime Museum, reached through a door to the right as you leave the Palace Museum (you need to ask the guide to take you to this part of the museum), now focuses on a fascinating collection of artefacts recovered from the Espadarte and Nossa Senhora da Consolação, shipwrecked in the waters off Fortaleza de São Sebastião in 1558 and 1608 respectively, and rediscovered in 2001.

The displays include the richest stash of Ming porcelain ever salvaged in Africa, comprising more than 1,500 pieces, many still in mint condition, whose motifs have been dated to the reign of the Chinese emperor Jiajing (1521–66). Also on display is a hoard of 16th-century gold and silver coins and other material from the two wrecks.

Sacred Art Museum

Situated in the same block as the Palace Museum but entered from around the corner (opposite Café-Bar Âncora d’Ouro), this small museum is housed in a wing of the Church of the Misericórdia, which still opens for Mass on Sunday mornings. The Misericórdia (House of Mercy) was a religious organisation with nominally charitable aims and a gift for raising revenue through bequests and later from a large prazo in Zambézia.

The church that houses the Sacred Art Museum served as the island headquarters of the Misericórdia from when it was built in 1700 until the organisation was disbanded in 1915, and the majority of artefacts it contains are the former property of the Church.

It might be difficult to get excited about the dozens of statues of saints displayed in the museum, especially after having spent time in the palace next door. The most unusual artefact is a Makonde carving of Jesus. It would be interesting to know when and how this statue was acquired, since it is very different in style and subject from most other Makonde carvings.

Other landmarks

Aside from the fortress and museums, the old town contains several buildings of considerable antiquity and/or architectural merit – indeed, most houses in this part of town are several hundreds of years old, and many have been restored to something approaching their former glory since the turn of the millennium.

The old Capitania (Port Authority) on the Largo de Capitania has an impressive entrance complete with a couple of anchors and a cannon. The old Customs House, alongside the Pontão (pontoon), is a magnificent building that has now been renovated and turned into loft apartments. If you ask the guard, he will usually let you in to have a look around.

There’s a rather stylised statue of the 15th-century Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama in the Praça da República outside the Palace Museum, while on the east side of the island, about 300m further south, is a similar statue of his approximate contemporary, the poet Luís Vaz de Camões, who is regarded as the Portuguese equivalent of Shakespeare (but had no direct links with Mozambique).

Inhaca Island

Situated about 35km from central Maputo, Inhaca is a dislocated extension of the narrow peninsula that runs northward from Maputo National Park to Cabo Santa Maria, from which it is separated by a shallow channel just 500m wide. Effectively forming the shore of Maputo Bay, Inhaca is among the most accessible of Mozambique’s many offshore islands, and ideally situated for a short break from the capital.

It luxuriates in an archetypal tropical island atmosphere, with a couple of good beaches, a mangrove-lined north coast and brightly coloured reefs off the west coast. The main tourist focus is Inhaca village, a tiny settlement dominated by a centre dotted with bars. The beach directly in front of the lodges is an interesting place to sit and watch the boats as the sun goes down.

Away from the village, the beaches on both the western side of the island (facing Maputo) and its eastern side (facing the Indian Ocean) are utterly deserted, and offer mile after mile of sun-kissed, wave-swept sand. The reefs of Inhaca are among the most southerly in Africa and, as the water in the gulf is 5°C warmer than elsewhere at this latitude, the island has been a centre of scientific research since 1921. The island is host to nearly 300 species of birds, while 490 fish species and more than 70 types of coral live in the surrounding waters.

Marine Biology Station

Inhaca has been a centre of scientific research since 1951. An interesting marine biology research station run by Maputo’s Eduardo Mondlane University lies to the south of Inhaca village, along with a well-kept museum of natural history (US$2.50). The museum has a complete skeleton of the endangered dugong, as well as many varieties of marine life preserved in fluid.

In 2016, with renewed investment, the station built a new residential building for graduate and resident researchers, and received a new research vessel as well as equipment required for its continued work in the Indian Ocean. For those with a strong interest in the island’s ecology, it’s worth trying to get hold of a copy of The Natural History of Inhaca Island, a 395-page book that includes comprehensive species descriptions of the fauna and flora as well as line drawings depicting the more common species.

The lighthouse

A good walk (around 3 hours each way), through grassland, local fields, salt flats and mangroves to the northern tip of the island. Take the road south of the airport and keep checking with the people you meet – asking ‘O caminho para farol?’ and pointing should do the trick. You must take water.

The lighthouse is now derelict and closed but the beaches are well worth a visit, being both deserted and vast. If you’re interested in riding the surf, you’ll need to head here, but given the distance you might prefer to organise a lift. Ask at your accommodation or in the village for transport options; return fare is around US$35.

The west beaches

You can walk all the way around the island should you wish, but a good alternative is to take the west side from the jetty down to the marine station – mile after mile of perfect deserted beach. It’s worth stopping every now and again just to listen to the waves on the shore and the wind in the palm trees.

It’s almost impossible to believe that you’re only a short distance from Maputo, until you look to the horizon where you can still make out distant buildings gleaming in the sunlight. The walk takes 1½–2 hours each way, and check the state of the tide – it may not be passable at high spring tides, and there are one or two places where you’ll need to scramble over rocks, so sandals are a good idea.

Birdwatching

With more than 300 species recorded in an area of only 40km², Inhaca offers some very good birding, with a variety of marine species alongside those more associated with coastal thickets and scrub. Among the most striking or beautiful species associated with vegetated habitats are the African fish eagle, trumpeter hornbill, green pigeon, Narina trogon, African hoopoe and green twinspot, while the sandy shores of the island often host large mixed groups of migrant and resident waders, ranging from the localised crab plover, flamingoes and bulky curlew to diminutive sandpipers and stints.

Pelicans and cormorants are common around the bay, while offshore birds, most likely to be seen in flight, include half a dozen species of tern (including the localised black-naped tern), three types of skua, Cape gannet and Pintado petrel.

Ilha dos Portugueses

A small island to the north of Inhaca itself, this island is now a protected area, managed by the Marine Biology station on Inhaca. In Portuguese colonial times it was a leper colony, and there are supposedly some ruins from those days, although they haven’t been found again since the 1960s. The beaches tend to be very flat with large sandbanks at low tide.

Take a boat from Inhaca – ask at the lodges for help arranging this. The best swimming beach is the one facing Inhaca, but it is dangerous to swim out too far as the current is very strong. You can walk round Ilha dos Portugueses in approximately 1½ hours.

Inhambane

The eponymous capital of Inhambane Province lies on the eastern shore of Mozambique’s Inhambane Bay, an attractive natural harbour formed by a deep inlet at the mouth of the small Matumba River. It is the oldest extant settlement between Maputo and Beira, and one of the more substantial, with a population estimated at 82,000 and a distinctly Mediterranean character, thanks to its spacious layout of leafy avenues lined with eye-pleasing if faded colonial buildings.

There is an abundance of NGOs operating out of town which may partly explain the good selection of eateries and other tourist amenities. This, in short, is an unusually pleasant and characterful town, and while most travellers treat Inhambane as nothing more than a passing stop en route to the nearby beaches at Tofo and Barra, it is worth an overnight stay, possibly before crossing the bay to Maxixe to catch an early morning bus north or south.

Inhambane today is anything but the bustling trade centre that it once was – it is difficult to think of a more tranquil town anywhere on the East African coast. The seafront itself is very pretty, particularly at sunset, though swimming in the murky water might not be such a great idea.

Most of the older buildings are clustered around an open square at the jetty end of Avenida da Independência, and can be visited on foot within an hour or so. It’s a pleasant walk just for the sake of the architecture, a peculiar mix of classic Portuguese with African and Muslim influences. The following buildings are of special note.

Church of Our Lady of Conception

Probably the most distinctive building in Inhambane, this Catholic edifice stands on the site of an earlier wooden church shown on the original 17th-century Portuguese plan of the town. The present building was constructed between 1854 and 1870, and its striking clocktower dates to the 1930s, when the clock was donated by a wealthy local family.

The church fell into disuse in the late 20th century, but was partially restored – apart from the collapsed roof – and now serves as a library, with a few English and other European-language books. It is the only building on one side of the street (which was surely named with deliberate irony), while the squat modern cathedral towering over it opposite is the only building on the other.

Museu de Inhambane

Though not exactly a ‘must see’, this moderately diverting museum, established in 1988, probably deserves 15 minutes of your time.

It houses a seemingly arbitrary selection of African musical instruments and household items, imported oddities (such as vintage radios and trunks) and displays relating to the history of the railway, as well as some photographs of the town taken in the 1920s. Some explanations are in English, but mostly in Portuguese.

Ship’s Lookout Building

Situated a block up from the jetty, this was built between 1940 and 1950 in a style known as Streamline Moderne, a development from Art Deco. Its lines supposedly resemble those of a ship’s prow, and it is now a general store. The Ciné-Teatro Tofo dates from the same period and is in the same style.

Old and new mosques

Situated near the corner with Rua da Mapai, the old mosque is an attractive small building, originally built between 1840 and 1860 using French brick and stone quarried near Maxixe; it was restored in 1928 and again in 1985.

Just a short walk up the street, is the new mosque, Massdjid Nuro Muhamad, completed in 1970, also worth a look, with decorative minarets and a green-painted dome. Visitors are welcome at both mosques, provided they are dressed appropriately.

Hoffman House

With its ornate façade and wraparound balconies, this two-storey building is one of the most ostentatious in Inhambane, brightly painted in bubble-gum pink and blue.

Built in the late 19th century using stones quarried near Ilha de Moçambique, it was originally the home and shop of the merchant Oswald Hoffman and later served as a hotel, while today it’s home to a printing press.

Escola 7 de Abril

Built as a school in the late 19th century (a function is still serves today), this building is notable for its classical lines and extended front archway.

The municipal office on Avenida da Independência is similar in style and vintage, as is the waterfront TDM office diagonally opposite the port.

Casa dos Arcos

Built in the late 19th century, possibly as a church or hotel, the enigmatic ‘House of Arches’ was extended to a second floor, reached via an internal spiral staircase, in the early 20th century and boasts several interesting classical features, including arched doors and windows, crescent-shaped nooks and stone column.

Maputo

The largest urban centre in Mozambique, Maputo is a bustling and attractive port city that has served as the national capital since 1898, when it was known as Lourenço Marques (LM for short). It lies on the Gulf of Maputo (formerly Delagoa Bay) in the far south of Mozambique, within 100km of the South African and Eswatini borders. As such, it often feels more strongly connected to South Africa than to the rest of Mozambique, a circumstance reflected in a popular saying that likens Mozambique to a funnel – all the money flows down south!

Arrive in Maputo without prejudice and it is, quite simply, a most likeable city – as safe as any in Africa, and with a good deal more character than most. The avenidas, lined with jacaranda, flame and palm trees and numerous street cafés, have a relaxed, hassle-free, Afro-Mediterranean atmosphere that is distinctively Mozambican.

They are flanked by any number of attractive old colonial buildings in various states of renovation and disrepair, ranging in style from pre-World War I Classical to later Art Deco, all dwarfed in places by various incongruous high-rise relics of the 1950s and 1960s, when the city was something of a laboratory for devotees of the Bauhaus architectural style.

Natural History Museum

Housed in one of the finest buildings in Maputo, a palace built in the Manueline style (a sort of Portuguese Gothic) and decorated with wonderfully ornamental plasterwork. Some of the animals are quite crudely stuffed and a few have rather unrealistic poses, but they’re worth a visit just to get a close-up view of the animals you might only catch a glimpse of in the wild.

Also on display is a series showing the development during gestation of elephant embryos, proudly announced as the only such display in the world. Don’t miss the ethnographic room, with a small but fine collection including carved wooden headrests, musical instruments, boats and ritualistic carvings.

Museu dos CFM

One of the better-quality museums in Maputo, this museum, housed in the Railway Station, opened in 2015 during an extensive renovation of the historic Beaux-Arts building.

It has an excellent permanent collection of maps, photos and railway memorabilia that tell the story of the port and railway industry in Mozambique. Plans are also in waiting to host temporary exhibitions, guided tours, special train rides and other cultural activities.

Núcleo de Arte

A very popular and cutting-edge collective where artists can work and display their pieces, this also has quite a good café, serving drinks and meals during the week and light snacks at weekends (around US$5 a dish), and occasional exhibitions. It was involved in a rather famous project to make sculptures from old AK47 guns, landmines and other weapons associated with the civil war, most notably by the artist Gonçalo Mabunda.

Several of the results of this experiment are on display here, and in the windows of an adjacent bank. There’s live music (typically marrabenta and jazz) here on Sunday evenings from 17.00 to 21.00 as well (US$4).

City walks

Maputo lends itself to casual exploration on foot, with several interesting colonial buildings and a colourful street life. Walking around the Polana district is particularly pleasant on a Sunday when the streets are quiet and most of the hawkers are sleeping off the previous night’s revelries.

For more information on recommended walks around Maputo, see our guide to exploring the city on foot.

Gorongosa National Park

Extending over 4,067km² at the southern end of the Rift Valley, Gorongosa National Park was Mozambique’s flagship conservation area in the last years of the Portuguese colonial era, when it was widely regarded as one of the finest safari destinations anywhere in Africa, rivalling the Serengeti for its prodigious concentration of wildlife.

Gorongosa has been through some lean times since then, particularly during the post-independence civil war, but it is now well on the road to recovery and, following the welcome intervention of the Carr Foundation in 2004, there is some cause for optimism that it might yet reclaim its place as one of the region’s finest wildlife destinations.

Realistically, Gorongosa has some way to go in attaining this goal. For aficionados of the Big Five, there is a sporting chance of encountering lion and elephant, which are both increasing in number and reasonably habituated to vehicles, but buffalos are scarce, leopards are predictably furtive and rhinos are – no less predictably – extinct. Still, even as things stand, Gorongosa is unquestionably the best non-marine wildlife-viewing destination in Mozambique, with the floodplains around Chitengo in particular supporting large and rapidly increasing herds of waterbuck, reedbuck, impala and other antelope.

If most safari-goers might need a little persuasion to give Gorongosa a try, birdwatchers should have no such qualms: the park’s tangled bush and mesmerising waterways are literally teeming with avian activity, and there is the added bonus of potential day visits to nearby Mount Gorongosa and its eagerly sought endemic race of green-headed oriole.

Exploring Gorongosa National Park

While it used to be permissible to explore the park with your own 4×4, such access was suspended in 2015.

Instead, visitors to Montebelo Gorongosa Lodge and Safari (Chitengo Camp) can sign up for reasonably priced guided game drives for US$40/40/45 per person every morning, noon and afternoon, respectively, or full-day drives for US$110 per person. Other tours on offer include a Gorongosa Mountain and coffee project day trip, for US$120 per person, canoe safari on the Pungué River for US$50 per person (min 2 people), walking safari for US$55 per person (min 2 people), boat safari on Lake Urema for US$55 per person (min 3 people), and a community bicycle tour for US$30 per person.

Should self-drive permission return, an excellent short drive from Chitengo follows Road 1 north to the Mussicadzi floodplain, from where you can follow Road 4 up the east side of the plain or Road 9 up the west side. While you are heading out this way, be aware that the pan alongside Road 1 between the junction with roads 2 and 3 is a favoured drinking hole for the shy but beautiful nyala and sable antelope.

On the floodplain, you’ll see plenty of waterbuck, reedbuck, impala, oribi and warthog in this area, as well as a dazzling selection of waterbirds, and most likely a few troops of baboon (officially listed as yellow baboon, but some experts believe that the population here is intermediate with the Chacma baboon and may warrant a unique subspecific status).

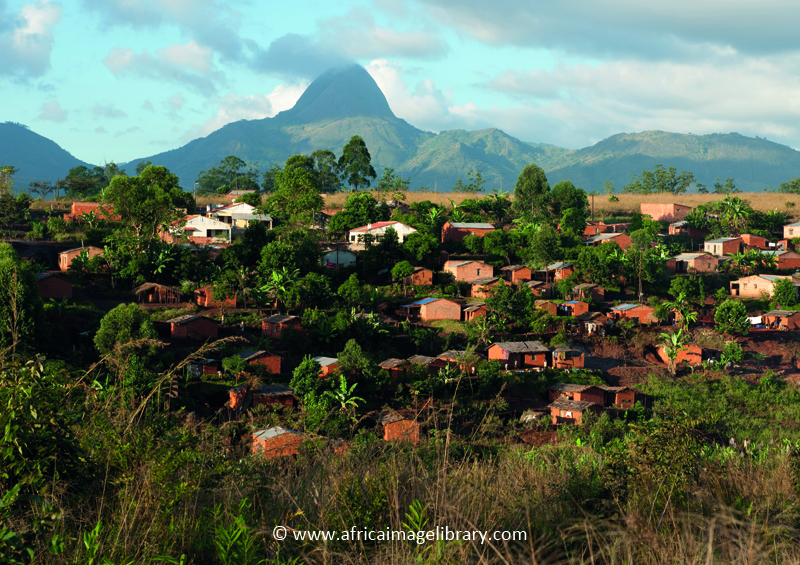

Gurué

Surrounded by orderly tea plantations and immense granite protrusions, the breezy market town of Gurué sits at an altitude of 720m in the fertile green foothills of the southern Rift Valley. It is the eleventh-largest town in Mozambique, with a population estimated at 145,000, a comparatively moist and cool climate, and an energised, bustling mood absent from many of its more torpid coastal cousins.

Gurué’s relatively temperate climate is a refreshing change from the coastal heat, and the immediate environs offer some good opportunities for relaxed rambling in scenic surrounds (recalling the Mulanje and Thyolo districts of neighbouring Malawi), but the major attraction here is Mount Namuli, one of Mozambique’s premier hiking and birding destinations.

The town itself is of limited architectural interest, mostly dating to the post-World War II era, but there is a rather pretty small chapel, with some colourful murals inside, at the northeast end of Avenida República.

Gurué’s biggest attraction is the surrounding countryside, which offers probably the best walking you’ll find in Mozambique. A nice easy walk is to tour the tea plantations that surround the town. Head out of town on the main road north past the hospital and then take the road off to the left and within 5 minutes you’ll be surrounded by tea bushes. It’s an extremely pleasant walk and very photogenic.

A more serious walk is the hike up Mount Namuli, which requires three days/two nights on foot from Gurué, as well as a good head for heights for the final ascent, though theoretically it could be done in a (very rushed) day with a private 4×4 to get you to the base camp.

Mount Namuli

Mozambique’s second-highest peak at 2,419m, Namuli is a massive granite dome that protrudes a full kilometre above a grassy rolling plateau incised with numerous streams and gorges. The main peak of Namuli lies only 12km northeast of Gurué, but is not visible from the town itself. Several other tall domes stand on the same plateau, and the entire massif comprises almost 200km² of land above the 1,200m contour.

Popular with hikers for its lovely green upland scenery, Namuli is also a mountain of great biological significance, supporting a variety of montane habitats including some 12km² of moist evergreen forest that shows some affiliations to the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania. Two main patches of forest remain: the larger but relatively inaccessible Manho Forest, which borders the Muretha Plateau about halfway between Gurué and Namuli Peak, and the more accessible Ukalini Forest at the southwest base of the granite cliffs below Namuli Peak.

Vincent’s bush squirrel, listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, is endemic to these forests, which also support samango and vervet monkey, red and blue duiker, various small carnivores and at least one endemic but as yet undescribed species of pygmy chameleon.

Whether you are there for the scenery or the fauna, the normal springboard for exploring Namuli is the village of Mukunha (also known as Muguna Sede), which lies on the southeast footslopes about 30km from Gurué.

A rough road leads from Gurué to Mukunha, heading north from the Mocuba road just past the hospital, but there is no public transport so, unless you have a private 4×4, the only option is to hike, a beautiful but long and tough trek that takes 8–10 hours and requires a guide; Luis Dos Santos Cotxane has been recommended, and he or another guide can be arranged through Pensão Gurué.

Cascata de Namuli

The best known of several spectacular waterfalls on the western side of the massif, the Cascata de Namuli is formed by the Licungo River as it cascades about 100m down a sloping rock face north of Gurué. It is an excellent goal for a day walk, a 5–6-hour round hike out of Gurué that passes through a variety of habitats, including the tea plantations of the Chá Zambezi Estate, stands of bamboo and small patches of indigenous forest, and you can swim in a pool above the waterfall. The riverine forest above the waterfall reputedly shelters the Namuli apalis and other rare birds, but it is unclear whether these range as far down as the waterfall itself.

To get there, follow the road past the Residencial Licungo out of town and keep going – you can’t really go wrong, and if in doubt anybody will point you in the right direction (just ask for ‘cascata’).

The road to the waterfall passes through the tea estate and although no charge is levied to walk to the waterfall, nor is any prior permission required, people driving may be required to park at the estate entrance gate and to do the last stretch on foot (about 1 hour each way).

Casa dos Noivos

Situated in the hilly countryside north of Gurué, the Casa dos Noivos is an abandoned hilltop dwelling that must have been very beautiful in its prime, and that still offers one of the most spectacular views in the region, over a rolling series of verdant valleys below Mount Namuli. The origin of its name (literally ‘House of the Bride and Groom’) is unclear: it may be that the house was built for a newlywed couple or simply that it is known locally as a place for romantic assignations.

On foot, the casa can be reached by following the Mocuba road out of town past the hospital, then taking the second road to the left and heading more or less north for about 90 minutes, passing through scenic tea estates en route. If you are thinking of driving, the road is very winding with some vertical drop-offs, so a 4×4 may be necessary, especially after rain.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Mozambique:

Related articles

Discover a whole other world in Mozambique’s waters.

A walking tour of Maputo is the perfect way to discover all that this exciting city has to offer.

From exploring the magnificent coastline to visiting historic towns, this is what you shouldn’t miss on a holiday in Mozambique.