Written by Laura Pidgley

Like most tourists, I was drawn to Uzbekistan by its treasure trove of Silk Road wonders – the elaborate mosques, towering minarets and lapis-blue madrassas of Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand. Of course, the architecture is outstanding – some of it really does have to be seen to be believed – but, aside from the turquoise tilework, it is the country’s people that provide the lasting memories.

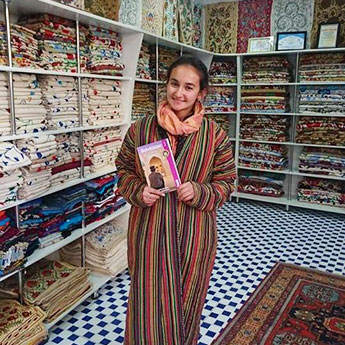

The second thing you’ll notice about the Uzbeks is that they are keen to show off their arts and crafts. The country has long been known for its textiles, most notably the suzani, a traditional Uzbek embroidery used to adorn walls, tables and beds. While in Bukhara (Uzbekistan’s embroidery capital) I met Vazira, a young girl who helps out in her mother’s Suzani Shop on Haqiqat Square. Keen to practise her already near-perfect English, she keenly offered to give me a brief demonstration. ‘There are three main stitches,’ she explained while working on a half-finished suzani, ‘and traditional Uzbek patterns used are suns, pomegranates, peppers and birds’. I later learned from my tour guide that these motifs stem from the 18th and 19th centuries, when an Uzbek woman was expected to present a suzani to the mother of her prospective husband in her wedding dowry. In a time when girls wore paranjas (known today as burqas) to obscure their faces, these suzanis provided an insight into a woman’s desires – suns represented life, pomegranates symbolised fertility, birds signified wisdom and peppers were protection from the evil eye. A suzani with many pomegranates, therefore, showed a woman who wished to have lots of children, a trait a mother would value highly when looking for her son’s wife.

Away from handicrafts, Uzbekistan is also regarded as having the widest range of musical styles in central Asia and, having met Babur in Samarkand, I can only agree. After wandering in to his small shop in a converted student cell of the Sher Dor Madrasa, he played his way through his country’s musical heritage, demonstrating a variety of different instruments: the dutar, a long-necked two-stringed lute; the doira, a goat-skin drum with jingles traditionally used at weddings; and my personal favourite, the chang, Uzbekistan’s answer to the harp.

What was so humbling about these demonstrations was that there was no pressure to buy – Uzbeks are overwhelmingly proud of their heritage, and are more interested in demonstrating their culture to visitors than turning on the ‘hard sell’. I did, however, purchase a beautifully embroidered table-runner from Vazira – she was so pleased that her demonstration had led to a sale, she also gave me a small suzani as a parting gift (which, incidentally, included lots of pomegranates).

The final trait common of people in Uzbekistan is their welcoming nature. Be it the hotel porter, taxi driver or the person you ask for directions in the bazaar, you’ll be greeted with a (gold-toothed) grin and genuine, unadulterated kindness. I encountered this warmth most memorably in Khiva, when I was approached by a group of guys taking selfies in chugirmas, sheepskin afro-style hats traditionally worn by men in the region. After the inevitable round of photos, they beckoned me to follow them. Ignoring my mother’s voice in my head not to go off with strange men, I obliged, and after a few minutes of walking through the streets of the Ichon Qala found myself at the Pahlavan Mahmud Mausoleum. I’d been here the previous day with my guide, when our tour group had been the only people exploring the 17th-century complex. Today, though, it was a riot of activity with people hastily making their way in to the summer mosque, and it was not until I saw the two girls in marshmallow-like dresses that I realised why – it was a wedding. A double wedding.

I was invited to watch the proceedings, where the brides and grooms and their families sat cross-legged around a table while the imam blessed the couples as he broke bread. The ceremony was surprisingly short – there were no vows or hymns, and barely five minutes had passed before people were moving from the mosque to the restaurant for the wedding party. I never got the chance to congratulate the happy couples, nor did I learn the names of my hat-wearing friends (their English was as bad as my Uzbek), but I was humbled to have been a party to their party nonetheless. Sometimes, it pays to ignore your mother’s advice.

Inspired to visit? Get 10% off our Uzbekistan guide: