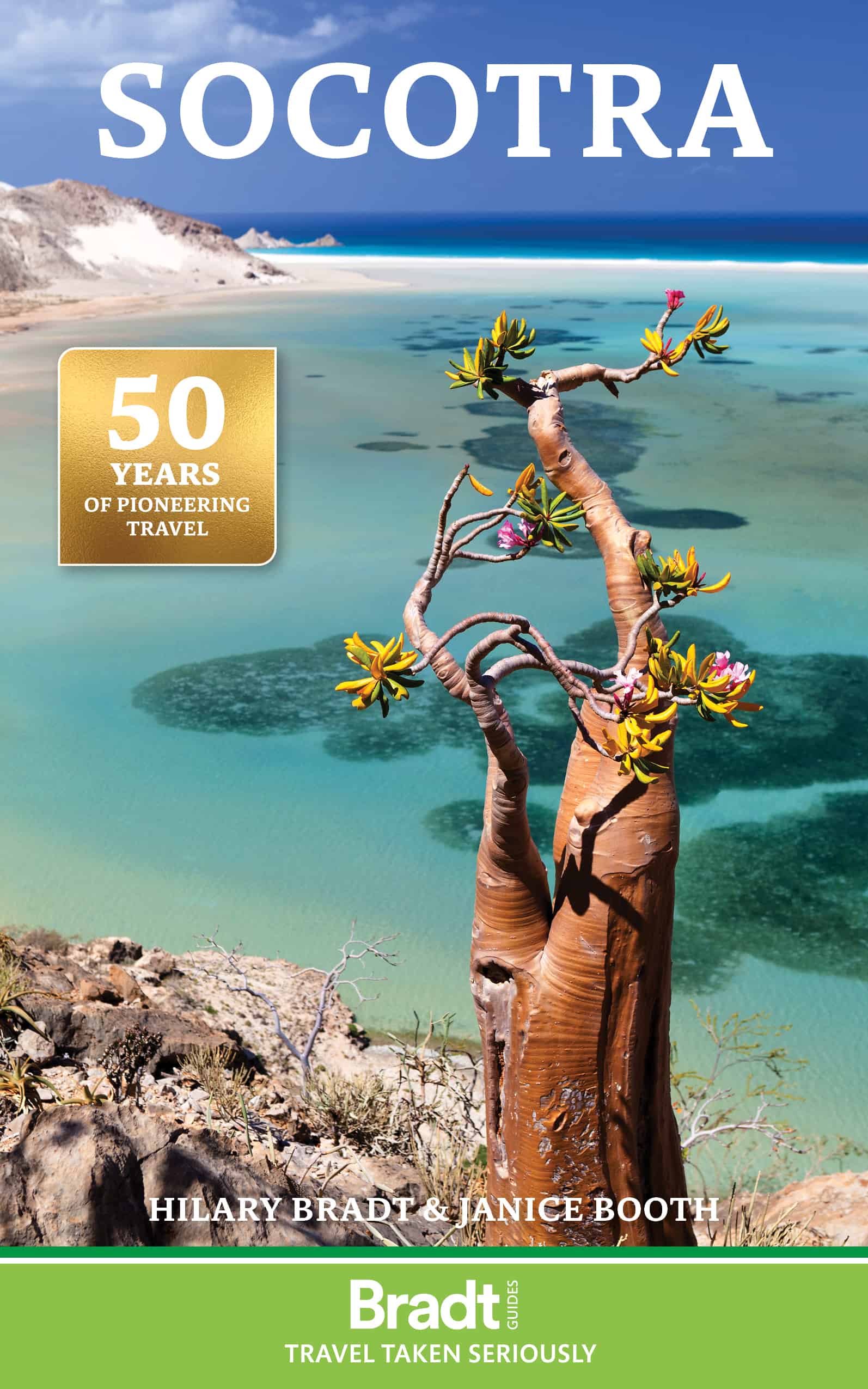

Socotra (ebook)

Publication Date: 12th Dec 2024

£16.99

Socotra travel guide. Expert travel tips and holiday advice for the largest island of the Socotra (Soqotra) archipelago off the coast of Yemen. Includes everything from Hadiboh hotels and restaurants to tour operators, eco-campsites, beaches, snorkelling and diving, endemic wildlife and flora including dragon blood trees and desert roses.

Edition: 2

Number of pages: 192

About this book

The new, thoroughly updated second edition of Bradt’s Socotra remains the first and only guide available to the largest of the four islands that make up the Socotra Archipelago in the Arabian Sea, 240 miles offshore from their mother land, Yemen.

A UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site packed with dramatically varied and essentially undisturbed landscapes (mountains, forest, ravines, sand-dunes, beaches, caves…), Socotra is unique. Sometimes known as ‘The Galapagos of the Indian Ocean’, the archipelago has an exceptionally large number of species found nowhere else in the world (‘endemic’) in an area smaller than Rhode Island. Accordingly, wildlife-watchers love Socotra: of 220 bird species recorded, 11 are endemic, while more than 300 plant species are endemic, as are all the land snails, 90% of reptiles and about 60% of spiders.

Socotra offers much to fascinate the adventurous traveller. Visitors may snorkel from boats or pristine beaches; camel-trek into mountains formed by volcanic activity; gawp at bizarre plants – dragon blood trees that resemble huge, fuzzy-topped umbrellas and giant desert roses; engage with Socotra’s rich history, which stretches back to the Stone Age and includes ancient cave art; and lunch at delightful fishing villages.

Bradt’s full-colour guide covers everything needed for a successful visit, including pre-departure planning, getting there, tour operators, where to stay and what to see. Background information on history, people, language and culture is followed by an easy-to-follow geographical breakdown covering all parts of the island, from the capital Hadiboh to Ayhaft Canyon National Park, Qaria lagoon, Rosh Marine Nature Sanctuary, Homhil Nature Sanctuary, Terbak village, Hoq Cave, Qalansiyah, Diksam plateau and Firmihin Forest.

To preserve its fragile environments, the recent growth in tourism – enabled by recent improvements in transport links and resulting in expansion of tourist infrastructure – is being handled with extreme care. Strict regulations are in force to preserve the island’s natural heritage and nearly three-quarters has protected status. This pristine and relatively unknown little island, so full of natural treasures, may be on the brink of a very different future. Responsible tourism is paramount, so let Bradt’s Socotra be your guide to this captivating island.

Before ordering ebooks from us, please check out our ebook information.

About the Author

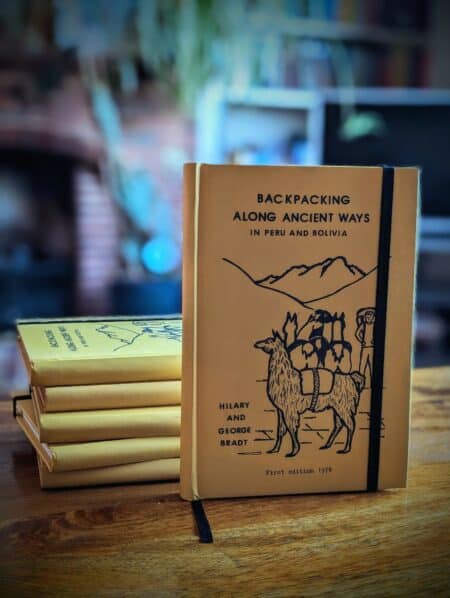

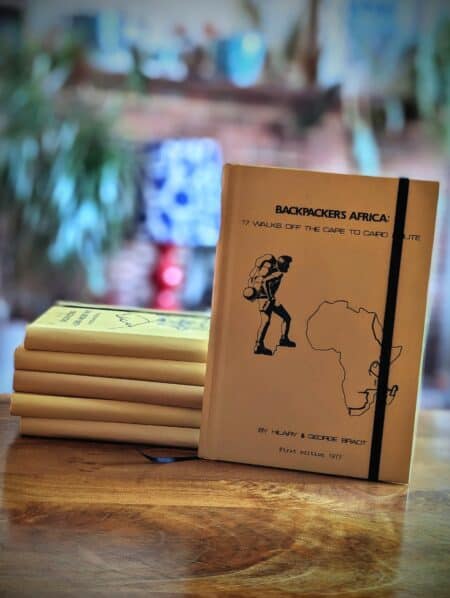

Hilary Bradt founded Bradt Travel Guides accidentally in 1974 while backpacking with her then-husband George through South America. Though semi-retired she is still involved with the company, mostly in trying to persuade sceptical staff to publish guides to places no-one has heard of. She assumed that after 30 or so years of roughing it, and an MBE, she had finally earned the right for some comfort, and even managed a stint as lecturer on a luxury ship. But then along came Socotra… Ever since seeing images of Socotra on a David Attenborough programme, Hilary had wanted to go there. Socotra meshed perfectly with her interest in off-the-beaten-track destinations and enthusiasm for wildlife, so visiting – and writing a Bradt guidebook to the island – became a no-brainer. When not travelling, Hilary lives in Devon, UK.

Until her death in February 2023, Janice Booth’s working life included professional stage management, archaeology, working for a Belgian NGO, compiling logic-puzzle magazines and travelling widely. She drove Land Rovers in Timbuktu, walked with water-buffalo in Tamil Nadu, waded in the breakers of Namibia’s Skeleton Coast, and edited many Bradt guides to various far-flung places. Having seen the positive effect that guidebooks can have on countries recovering from war – particularly through personal experience of writing Bradt’s Rwanda and editing Bradt’s Mali – Janice was keen to visit and write about Socotra in the hope that this guide may also help to encourage visitors. After moving to Devon, she co-authored (with Hilary Bradt) Slow South Devon & Dartmoor and Slow East Devon & the Jurassic Coast.

Chris Miller was born and bred in New Zealand, but after finishing a degree in computer science there, he followed a job to Australia before moving on to Canada and then London, where he currently works as a software developer. With so many countries and cultures within easy reach he has found London to be the perfect base to explore the world, and his love of travel has grown from there. He has always had a strong interest in wildlife and the natural world, preferring the most remote corners of the planet to anywhere heavily populated. His interest in photography has evolved naturally alongside the travelling, as it provides an ideal way to capture and share memories and moments from the far-flung corners of the world he loves to explore. He contributed to the first edition of Bradt’s Socotra guidebook, and is co-updater of the second edition.

Miranda Lindsay-Fynn’s working life has included being a yacht captain, actively planning voyages and cruises all over the world, including several ocean crossings. Her experience as a captain has helped her develop many useful skills, from celestial navigation to knowing her way around a diesel engine. More recently, she has found her niche as a marketing director for SMEs and start-ups, a world that can be equally as wild and turbulent to navigate as the ocean. Alongside her marketing endeavours, she continues to embrace her love for sailing and exploring extraordinary places. She contributed to the first edition of Bradt’s Socotra guidebook, and is co-updater of the second edition.

Additional Information

Table of ContentsIntroduction

PART ONE: GENERAL INFORMATION

Chapter 1: Background information

Chapter 2: Practical information

PART TWO: THE GUIDE

Chapter 3: The North

Chapter 4: The East

Chapter 5: The Centre and the South

Chapter 6: The West and the Outer Islands

Appendices: Further information, Language, Socotra nature – protected by law, Checklist of endemic species in this book

Index