Written by Bradt Travel Guides

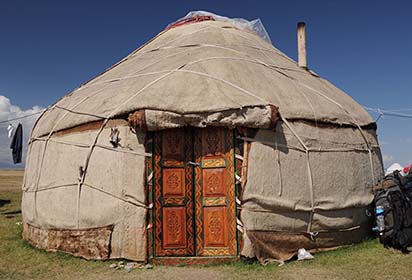

In the pre-Soviet era, the yurt was at the centre of Kyrgyz life © Pavel Svoboda, Shutterstock

In the pre-Soviet era, the yurt was at the centre of Kyrgyz life © Pavel Svoboda, Shutterstock

Before the Soviet period and the collectivisation of a nomadic lifestyle, the yurt – the round, felt-covered tent that has been the traditional dwelling throughout central Asia for centuries – was the centrepiece of Kyrgyz life. Since independence there has been a move back to a nomadic way of life or, as in many cases, a compromise lifestyle in which several months of the year are spent grazing livestock at an alpine jailoo and the rest settled in a village in the valleys. These days, Russian-made tractors and battered Zhigulis may have replaced the beasts of burden of earlier times, and some yurts may have the dubious benefit of battery-operated television sets, but to observe the gentle rhythm of the daily routine at a summer jailoo is to witness a way of life that has remained basically unchanged for millennia.

The daily routine starts early at a jailoo. Women start cooking breakfast at dawn and, once their menfolk have set off to lead their herds to pasture, they see to their other daily tasks such as cleaning, making kumys (fermented mare’s milk) and kajmak (cream). Rarely do they move far from the yurt, unlike the men who often spend the whole day on horseback with their herds, only returning to the warmth and comfort of the yurt as dusk falls. The yurt is a unique type of moveable dwelling that can be found from Mongolia in the northeast to Turkish Anatolia in the southwest, but they are most numerous in the lands of the Kyrgyz, Kazakhs and Mongols. Yurts have been around for thousands of years; they were described by Marco Polo on his travels in central Asia, who was astonished to see nomads travelling the land with their homes disassembled in carts. The structure of a yurt is simple but highly effective: a criss-cross framework of wooden laths, rather like a wall-trellis for climbing garden plants; a thick felt covering to keep the elements out; and a heavy wooden tunduk which is the centrepiece for the wooden struts that hold the roof in place and surround the smoke-hole. The basis behind the yurt’s design is that of strength, warmth and portability; their design is such that they may be taken down and reassembled within a matter of hours, and the materials, although bulky and heavy, can be carried on the backs of a few horses, or more likely on a trailer tugged along by a Russian car.

Erecting a yurt

Yurts, which in Kyrgyzstan are usually referred to as bozoy (‘grey house’) because of the grey sheep’s wool that was used to make the poorer-quality felt of the past, are constructed entirely without the use of nails – instead, all of the wooden members are lashed together with leather straps. The setting-up procedure begins with the door frame (the bosogo), which is oriented to the southeast to catch the morning light. The round trellis wall (kerege) is attached to this, supported at intervals by long wooden poles, usually of birch or poplar, called kanat. Once the circular wall of kerege and kanat has been erected, the wooden struts that support the cupola are inserted into place and the tunduk raised and set in place. The tunduk is central to the entire structure and is without doubt the most valuable and least easily replaced part of the yurt framework. With all of the skeletal structure in place, the outer coverings of felt matting can be draped over the framework – successive layers that are called chiy, kiyiz, tuurduk and jabuu. The final layer is folded back from the tunduk in daytime, unless it is raining, to allow air to flow through the structure; in cold and inclement weather it is kept tightly shut. A final touch, if the yurt is new, is to toss a sheep’s head through the tunduk as a gesture of good luck.

Yurt interior

The yurt interior is laid out according to an age-old pattern. The fireplace goes directly below the tunduk, although many modern yurts have a flap at the side for the chimney of a stove that is set to the side. Behind the fireplace, opposite the entrance, is the stack of blankets, quilts and pillows known as the juk, which is piled high on top of chests and serves as an indicator of wealth. In front of the juk is the most prestigious position in the yurt, the tyor, which is reserved for the head of the family or guests of honour such as aksakalsand, inevitably, curious Western visitors. The less favourable, draughtier area close to the entrance is the space designated for the women of the household. Right of the entrance is the female half of the yurt, the eptchi zhak, where tasks such as needlework and dishwashing take place, and where knitting, embroidery and decorative bric-a-brac are kept. The opposite side, the erz zhak, is the preserve of men, and is the area where manly possessions like whips, knives and harnesses are kept.

For more on Kyrgyzstan, check out our comprehensive guide: