Namibia and trips there are changing. But every time I go, I am again surprised at how easy the travelling is, and how remarkable the country.

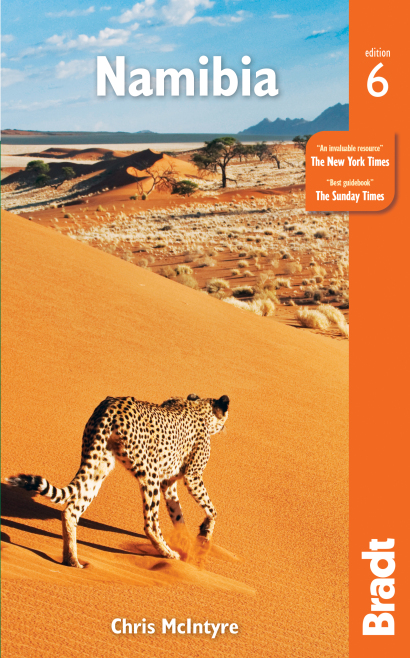

Chris McIntyre, author of Namibia: the Bradt Guide

Namibia is like a dreamscape: vast tracts of wilderness punctuated by stunning wildlife; eerie rock forms gouged out of the earth by the Fish River, and Sossusvlei’s towering red dunes. Yet for all its lonely landscapes, the country is eminently accessible to the independent traveller. With an excellent roadwork and very light traffic, Namibia is a joy for the self-driver. You don’t even need a 4×4 to marvel at herds of zebra and springbok at Etosha’s great saltpan, ponder ancient Bushman engravings at Twyfelfontein, or explore the unexpected lushness of the Caprivi Strip.

Of course, no holiday in Namibia is complete without a trip to the seaside – but this is no ordinary coastline. Eschew the beach in favour of kayaking amongst the seals and dolphins at Walvis Bay, brave the smell of the seal sanctuary at Cape Cross, or splash out on a once-in-a lifetime trip to the Skeleton Coast; you won’t be disappointed. And if you’re up for serious adventure, then take a 4×4 that’s fully equipped for camping and explore the vast desert emptiness of the Kunene region.

For more information, check out our guide to Namibia:

Food and drink in Namibia

Food

Traditional Namibian cuisine is rarely served for visitors, so the food at restaurants tends to be European in style, with a bias towards German dishes and seafood. It is at least as hygienically prepared as in Europe, so don’t worry about stomach upsets.

Namibia is a very meat-orientated society, and many menu options will feature steaks from one animal or another. If you eat fish and seafood you’ll be fine; menus often feature white fish such as kingklip and kabeljou, as well as lobster in coastal areas. Otherwise, most restaurants offer a small vegetarian selection, and lodge chefs will usually go out of their way to prepare vegetarian dishes if given notice.

Travellers with special dietary requirements, for example coeliacs, should be sure to notify the various hotels and lodges well in advance. While restaurant options have improved in recent years, the situation is patchy, so do bring glutenfree breads and snacks if you are likely to be away from the main centres. In the larger supermarkets you’ll find meat, fresh fruit and vegetables (though the more remote the areas you visit, the smaller your choice), and plenty of canned foods, pasta, rice, bread, etc. Most of this is imported from South Africa, and you’ll probably be familiar with some of the brand names.

Traditional foodstuffs eaten in a Namibian home may include the following: eedingu (dried meat), eendunga (fruit of the makalane palm, rather like a rusk), kapana (bread), mealiepap (form of porridge, most common in South Africa), omanugu (also known as mopane worms: imbrassia belina – these are fried caterpillars, often cooked with chilli and onion), ombindi (spinach), oshifima (dough-like staple made from millet) and oshifi ma ne vanda (millet with meat).

Drink

Alcohol

Because of a strong German brewing tradition, Namibia’s lagers are good, the Hansa and Windhoek draughts being particular favourites. In cans or bottles, Windhoek lager and Tafel – from around N$30 – provide a welcome change from brands such as Castle that dominate the rest of the subcontinent, and now the occasional craft brewery is putting in an appearance too.

Although wine served in restaurants is mainly South African, an increasing number of drinkable wines are being produced in Namibia. The top South African wines match the best that California or Australia have to offer, and at generally lower prices. You can get a bottle of palatable wine in a restaurant from around N$175.

Soft drinks

Canned soft drinks, from Diet Coke to sparkling apple juice, are available ice cold from just about anywhere – which is fortunate, considering the amount that you’ll need to drink in this climate. They cost about N$10 each, and can be kept cold in insulating polystyrene boxes made to hold six cans. These cheap containers are invaluable if you are on a self-drive trip, and not taking a large coolbox. They are available from some camping stores such as Cymot for about N$50.

In an Ovambo home you may be offered oshikundu, a refreshing breakfast drink made from fermented millet and water.

Water

The water in Namibia’s main towns is generally safe to drink, though it may taste a little metallic if it has been piped for miles. Natural sources should usually be purified, though water from underground springs and dry river-beds seldom causes any problems.

Health and safety in Namibia

Health

Sensible preparation will go a long way to ensuring your trip goes smoothly. Particularly for first-time visitors to Africa, this includes a visit to a travel clinic to discuss matters such as vaccinations and malaria prevention.

To help travellers prepare for a trip, the Bradt website carries a section on health in Africa (see above). While this elaborates on the information below, the following summary points are worth emphasising:

Immunisations

Having a full set of immunisations takes time, normally at least six weeks, although some protection can be had by visiting your doctor as late as a few days before you travel. No immunisations are required by law for entry into Namibia, unless you are coming from an area where yellow fever is endemic. In that case, a vaccination certificate is mandatory. To be valid the vaccination must be obtained at least ten days before entering the country.

It is wise to be up to date on tetanus, polio and diphtheria, hepatitis A and typhoid. Immunisations against hepatitis B and rabies may also be recommended. Immunisation against cholera is not usually required for trips to Namibia. Vaccination against rabies is now recommended for all visitors as there is an international shortage of rabies immunoglobulin (RIG), which is essential if you have not had three doses of vaccine before you travel. Experts differ over whether a BCG vaccination against tuberculosis (TB) is useful in adults: discuss this with your travel clinic.

Malaria

There is no vaccine against malaria, but preventative drugs are available, including mefloquine, atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone) and the antibiotic doxycycline. Malarone and doxycycline need only be started two days before entering Namibia, but mefloquine should be started two to three weeks before. Doxycycline and mefloquine need to be taken for four weeks after the trip and Malarone for seven days. It is as important to complete the course as it is to take it before and during the trip.

The most suitable drug varies depending on the individual and the country they are visiting, so visit your GP or a specialist travel clinic for medical advice. Be aware that no preventative drug is 100% effective, so carry a cure too.

It is also worth noting that no homeopathic prophylactic for malaria exists, nor can any traveller acquire effective resistance to malaria. Those who don’t make use of preventative drugs risk their life in a manner that is both foolish and unnecessary.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Namibia is not a dangerous country, and is generally surprisingly crime free. Outside of the main cities, crime against visitors, however minor, is exceedingly rare. Even if you are travelling on local transport on a low budget, you are likely to experience numerous acts of random kindness, but not crime. It is certainly no more dangerous for visitors than most of the UK, USA or Europe.

That said, there are increasing reports of theft and muggings, in particular from visitors to Windhoek, so here as in any other city it is important not to flaunt your possessions, and to take common-sense precautions against crime. A large rucksack, for example, is a prime target for thieves who may be expecting to find cameras, cash and credit cards tucked away in the pockets.

Provided you are sensible, you are most unlikely to ever see any crime. Most towns in Namibia have townships, often home to many of the poorer sections of society. Generally they are perfectly safe to visit during the day, but tourists should avoid wandering around with valuables. If you have friends or contacts who are local and know the area well, then take the opportunity to explore with them a little. Wander around during the day, or go off to a nightclub together. You’ll find that they show you a very different facet of Namibian life from that seen in the more affluent areas.

For women travellers, especially those travelling alone, it is important to learn the local attitudes about how to behave acceptably. This takes some practice, and a certain confidence. You will often be the centre of attention, but by developing conversational techniques to avert overenthusiastic male attention, you should be perfectly safe. Making friends of the local women is one way to help avoid such problems.

Car accidents

Dangerous driving is probably the biggest threat to life and limb in most parts of Africa. On a self-drive visit, drive defensively, being especially wary of stray livestock, gaping pot-holes, and imbecilic or bullying overtaking manoeuvres.

Many vehicles lack headlights and most local drivers are reluctant headlight users, so avoid driving at night and pull over in heavy storms. On a chauffeured tour, don’t be afraid to tell the driver to slow or calm down if you think he is too fast or reckless.

Wild animals

Don’t confuse habituation with domestication. Most wildlife in Africa is genuinely wild, and widespread species such as hippo or hyena might attack a person given the right set of circumstances. Such attacks are rare, however, and they almost always stem from a combination of poor judgement and poorer luck. A few rules of thumb: never approach potentially dangerous wildlife on foot except in the company of a trustworthy guide; never swim in lakes or rivers without first seeking local advice about the presence of crocodiles or hippos; never get between a hippo and water; and never leave food (particularly meat or fruit) in the tent where you’ll sleep.

Snake and other bites

Snakes are secretive and bites are a real rarity, but certain spiders and scorpions can also deliver nasty bites. In all cases, the risk is minimised by wearing closed shoes and trousers when walking in the bush, and watching where you put your hands and feet, especially in rocky areas or when gathering firewood. Only a fraction of snakebites deliver enough venom to be lifethreatening, but it is important to keep the victim calm and inactive, and to seek urgent medical attention.

Travel and visas in Namibia

Visas

Currently all visitors require a passport which is valid for at least six months after they are due to leave, a completely blank page for Namibian immigration to stamp, and an onward ticket of some sort. In practice, the third requirement is rarely even considered if you look neat, respectable and fairly affluent.

At present, British, Irish and US citizens can enter Namibia without a visa for 90 days or less for a holiday or private visit, as can nationals of other countries that include Angola, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Botswana, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Lesotho, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Macau, Malawi, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mozambique, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Russian Federation, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

That said, it is always best to check with your local Namibian embassy or high commission before you travel. If you have difficulties in your home country, contact the Ministry of Home Affairs and Immigration in Windhoek. The 90-day tourist visa can be extended by application in Windhoek. You will then probably be required to show proof of the ‘means to leave’, like an onward air ticket, a credit card, or sufficient funds of your own. The current cost of a tourist or business visa is N$500 plus handling fees.

Travelling with children

In Namibia parents travelling to, or through, the country are required by law to provide a full birth certificate for each accompanying child under the age of 18. This applies even when both biological parents or the legal guardians are present. The regulations on this are complex and controversial, even if the reasons for their implementation (to curb child trafficking and exploitation) are commendable.

If a child is travelling with only one parent named on the birth certificate, or with neither biological parent, things become even more complex and there has been a spate of passengers being denied boarding on flights or entry on arrival. Thus, if you are planning to travel with a minor, we strongly suggest that you check the latest information on this with your nearest Namibian high commission or embassy, well in advance of your departure date.

Getting there and away

By air

Windhoek has two small but modern airports: Hosea Kutako International Airport, which is generally used for international flights, and Eros, which caters mostly for internal flights and a few international flights. Be sure to check which one is to be used for each of your flights.

Air Namibia’s only direct flight to Windhoek from Europe is from Frankfurt, which connects easily with London. Flights depart in the evening in both directions, arriving early the following morning. Air Namibia also operates connecting flights to/from Johannesburg and Cape Town to link up with most of their intercontinental flights to/from Windhoek. For many European travellers, the best choice is to fly via Johannesburg. There’s a whole host of other options here, from many European airports. British Airways and South African Airways have daily overnight services from London, and both operate add-on connections to Windhoek, run by their subsidiaries. Virgin also services the Johannesburg route, though they do not have an add on to Windhoek so passengers have to use another airline.

Overland

Entering over one of Namibia’s land borders is equally easy – whether by car or by bus – as there are fast and direct links on good tarred roads with South Africa, Botswana and Zambia. Namibia’s few remaining passenger trains cover only internal routes, but those wishing to cross the border in style would do well to consider Rovos Rail’s Namibia safari.

Border crossings Namibia’s borders are generally hassle-free and efficient. If you are crossing with a hired car, then remember to let the car-hire company know as they will need to provide you with the right paperwork before you set off. Be sure to check the opening hours of the borders.

Getting around

Driving

Driving yourself around Namibia is, for most visitors, by far the best way to see the country. It is generally much easier than driving around Europe or the USA: many of the roads are excellent, the traffic is light and the signposts are usually clear, unambiguous and written in English.

Driving yourself gives you freedom to explore and to stop where you wish across the country, but it doesn’t restrict you to your car every day. When visiting private camps or concession areas, you can often leave your hire car for a few days, joining daily 4×4 excursions into more rugged country, led by resident safari guides. If possible, I’d recommend hiring a vehicle for your whole time in Namibia, collecting it at the airport when you arrive, and returning it there when you depart.

By air

Namibia’s internal air links are good and reasonably priced, and internal flights can be a practical way to hop huge distances swiftly. The scheduled internals are sufficiently infrequent that you need to plan your trip around them, and not vice versa. This needs to be done far in advance to be sure of getting seats, but does run the risk of your trip being thrown into disarray if the airline’s schedule changes.

Sadly, this isn’t as uncommon as you might hope. Increasingly, light aircraft flights, both scheduled and private charter, are being used for short camp-to-camp flights. These are pretty expensive compared with driving but are great if you are short on time, do not want to drive or want to visit areas that are otherwise confined to experienced off-road drivers. Air Namibia operates regular and relatively reliable flights around the region. These include daily flights from Windhoek to Cape Town and Johannesburg, from about N$2,000 one-way.

If you travel between Europe and Namibia with Air Namibia book your regional flights at the same time, as these routes become much cheaper. Prices and timetables of internal flights change regularly. South African Airways links Windhoek with Johannesburg.

In the last few years, there have been an increasing number of light aircraft flights around Namibia, arranged by small companies using small four- and six-seater planes as well as larger 16-seater ‘caravans’. These are particularly convenient for linking farms and lodges which have their own bush airstrips. If you have the money, and want to make the most of a short time in the country, then perhaps a fly-in trip would suit you. This is still the only way to see one or two of the private concessions in the extreme northwest.

By rail

Although an extensive railway network connects Namibia’s main towns, most trains carry freight rather than passengers. StarLine passenger trains, operated by TransNamib, are limited to the line between Windhoek and Swakopmund/Walvis Bay and the north–south service between Windhoek and Keetmanshoop, with onward connections to Karasburg, along with trains to Tsumeb and further north.

Trains are rarely full, but they are exceptionally slow and stop frequently, so are not for those in a hurry; most visitors without their own vehicle prefer long-distance coaches or hitchhiking. However, travelling by train affords the chance to meet local people and, as journeys are overnight (there’s no chance of enjoying the view), it allows travellers to get a night’s sleep while in transit, saving on accommodation costs and perhaps ‘gaining’ a day at their destination.

By bus

In comparison with Zimbabwe, East Africa or even South Africa, Namibia has few cheap local buses that are useful for travellers. That said, small Volkswagen combis (minibuses) do ferry people between towns, usually from townships, providing a good fast service, but they operate only on the busier routes between centres of population. Visitors usually want to see the more remote areas – where local people just hitch if they need transport. As an indication of fares, you could expect to pay around N$300 (£16.50/US$20) between Windhoek and Ondangwa, one-way.

When to visit Namibia

Although much of Namibia can seem deserted, individual places can often be very busy, especially around Easter and from July to the end of October. Many of the lodges and restcamps in and around Etosha, Damaraland and the Namib-Naukluft area are fully booked for the peak season as early as 12–18 months ahead, so advanced booking is essential at these times – and increasingly year round.

Outside of the peak months, though, there are times when you’ll find the lodges quieter and may even have some of the attractions to yourself. Avoid coming during the Namibian school holidays if possible. These are generally around 25 April–25 May, 15 August–5 September and 5 December–15 January. Then many places will be busy with local visitors, especially the less expensive restcamps and the national parks.

While there really are neither any ‘bad’ nor any ‘ideal’ times to visit Namibia, there are times when some aspects of the country are at their best. Consider your own specific requirements, as well as the weather, before you travel.

More information

- Expert Africa is a UK-based specialised tour operator run by the author of the Bradt guide to Namibia.

- SafariBookings is a comparison website that lists Namibia safari holidays run by local and international tour operators.

What to see and do in Namibia

Twyfelfontein rock engravings

Twyfelfontein was named ‘doubtful spring’ by the first European farmer to occupy the land – a reference to the failings of a perennial spring of water which wells up near the base of the valley. Formerly the valley was known as Uri-Ais, and seems to have been occupied for thousands of years. Then its spring, on the desert’s margins, would have attracted huge herds of game from the sparse plains around, making this uninviting valley an excellent base for early hunters. This probably explains why the slopes of Twyfelfontein, amid flat-topped mountains typical of Damaraland, conceal one of the continent’s greatest concentrations of rock art. When you first arrive, they seem like any other hillsides strewn with rocks. But the boulders that litter these slopes are dotted with thousands of paintings and ancient engravings, only a fraction of which have been recorded.

Declared a World Heritage Site in 2007, Twyfelfontein was unusual amongst African rock art sites in having both engravings and paintings, though today only engravings can be seen. Many are of animals and their spoor, or geometric motifs – which have been suggested as maps to water sources. Why they were made, nobody knows. Perhaps they were part of the people’s spiritual ceremonies, perhaps it was an ancient nursery to teach their children, or perhaps they were simply doodling.

Swakopmund

Considered by most Namibians to be the country’s only real holiday resort, this old German town spreads from the mouth of the Swakop River out into the surrounding desert plain, and is climatically more temperate than the interior. The palm-lined streets, immaculate old buildings and well-kept gardens of the centre give Swakop (as the locals call it) a unique atmosphere, and make it a hugely pleasant oasis in which to spend a few days.

Unlike much of Namibia, Swakopmund is used to tourists, and has a wide choice of places to stay and eat, and many things to do. The town has also established a name for itself as a centre for adventure travel, attracting visitors seeking ‘adrenalin’ trips to take part in options ranging from free-fall parachuting to dune-bike riding and sandboarding. This is still too small to change the town’s character, but is enough to ensure that you’ll never be bored. On the other hand, visit on a Monday during one of the quieter months, and you could be forgiven for thinking that the town had partially closed down!

Sossusvlei

The classic desert scenery around Sesriem and Sossusvlei is the stuff that postcards are made of – enormous apricot dunes with gracefully curving ridges, invariably pictured in the sharp light of dawn with a photogenic oryx or feathery acacia adjacent. Sesriem and Sossusvlei lie on the Tsauchab River, one of two large rivers that flow westward into the great dune field of the central Namib, but never reach the ocean. Both end by forming flat white pans dotted with green trees, surrounded by spectacular dunes – islands of life within a sea of sand.

The road from Sesriem to Sossusvlei is soon confined into a corridor, flanked by huge dunes. Gradually this narrows, becoming a few kilometres wide. This unique parting of the southern Namib’s great sand sea has probably been maintained over the millennia by the action of the Tsauchab River and the wind. Although the river seldom flows, note the green camelthorn (Vachellia erioloba) which thrives here, clearly indicating permanent underground water. Continuing westward, the present course of the river is easy to spot parallel with the road. Look around for the many dead acacia trees that mark old courses of the river, now dried up. Some of these have been dated at over 500 years old.

Most years, the ground here is a flat silvery-white pan of fine mud that has dried into a crazy-paving pattern. Upon this are huge sand mounds collected by nara bushes, and periodic feathery camelthorn trees drooping gracefully. All around the sinuous shapes of the Namib’s (and some claim the world’s) largest sand dunes stretch up to 300m high. It’s a stunning, surreal environment. Perhaps once every decade, Namibia receives really torrential rain. Storms deluge the Naukluft’s ravines and the Tsauchab sweeps out towards the Atlantic in a flash flood, surging into the desert and pausing only briefly to fill its canyon. Floods so powerful are rare, and Sossusvlei can fill overnight. Though the Tsauchab will subside quickly, the vlei remains full. Miraculous lilies emerge to bloom, and bright yellow devil thorn flowers (Tribulus species) carpet the water’s edge.

Surreal scenes reflect in the lake, as dragonflies hover above its polished surface. Birds arrive and luxuriant growth flourishes, making the most of this ephemeral treat. These waters recede from most of the pan rapidly, concentrating in Sossusvlei, where they can remain for months. While they are there, the area’s birdlife changes radically, as waterbirds and waders will often arrive, along with opportunist insectivores.

Meanwhile, less than a kilometre east, over a dune, the main pan is as dry as dust, and looks as if it hasn’t seen water in decades. Individual dunes afford superb views across this landscape, with some of the best from ‘Big Daddy’. It’s a strenuous climb to the top, looking out across to ‘Big Mama’, but the climb, followed by a long walk, is rewarded by the spectacle of Dead Vlei laid out below – and the fun of running down the slip-face to reach it.

Skeleton Coast

By the end of the 17th century, the long stretch of coast north of Swakopmund had attracted the attention of the Dutch East India Company. They sent several exploratory missions, but after finding only barren shores and impenetrable fogs, their journeys ceased. Later, in the 19th century, British and American whalers operated out of Lüderitz, but they gave this northern coast a wide berth – it was gaining a formidable reputation.

Today, driving north from Swakopmund, it’s easy to see how this coast earned its names of the Coast of Skulls or the Skeleton Coast. Treacherous fogs and strong currents forced many ships on to the uncharted sandbanks that shift underwater like the desert’s sands. Even if the sailors survived the shipwreck, their problems had only just begun. The coast here is a barren line between an icy, pounding ocean and the Namib Desert. It’s testament to the power of the ocean that, despite the havoc wreaked on passing ships, very few wrecks remain visible.

At first sight it all seems very barren, but watch the amazing wildlife documentaries made by the famous film-makers of the Skeleton Coast, Des and Jen Bartlett, to realise that some of the most remarkable wildlife on earth has evolved here. Better still, drive yourself up the coast road, through this fascinating stretch of the world’s oldest desert. You won’t see a fraction of the action that they have filmed, but with careful observation you will spot plenty to captivate you.

Sandwich Harbour

This small area about 45km south of Walvis Bay has a large saltwater lagoon, extensive tidal mudflats and a band of reed-lined pools fed by freshwater springs, together forming one of the most important birdlife refuges in southern Africa. Typically you’ll find about 30 species of birds at Sandwich. It offers food and shelter to thousands of migrants every year and some of Namibia’s most spectacular scenery – for those lucky enough to see it. It’s worth climbing up one of the dunes, as from there you can see the deep lagoon, protected from the ocean’s pounding by a sandspit, and the extensive mudflats to the south, which are often covered by the tide.

Windhoek

Namibia’s capital spreads out in a wide valley between bush-covered hills and appears, at first sight, to be quite small. Driving from the international airport, you pass quickly through the suburbs and, reaching the crest of a hill, find yourself suddenly descending into the city centre. As you stroll through this centre, the pavement cafés and picturesque old German architecture conspire to give an airy, European feel, while street vendors remind you that this is Africa. Look upwards! The office blocks are tall, but not skyscraping. Around you the pace is busy, but seldom as frantic as Western capitals seem to be.

Leading off Independence Avenue, the city’s main street, is the open-air Post Street Mall, centre of a modern shopping complex. Wandering through here, between the pastel-coloured buildings, you’ll find shops selling everything from fast food to fashion. In front of these, street vendors crouch beside blankets spread with jewellery, crafts and curios for sale. Nearby, the city’s more affluent residents step from their cars in shaded parking bays to shop in air-conditioned department stores.

Like many capitals, Windhoek is full of contrasts, especially between the richer and poorer areas, even if it lacks any major attractions. For casual visitors the city is pleasant; many stop for a day or two, as they arrive or leave, though few stay much longer. It is worth noting that much of the city all but closes down on Saturday afternoons (although some shops open on a Sunday morning), so be aware of this if you plan to be in town over a weekend.

Etosha National Park

Translated as the ‘Place of Mirages’, ‘Land of Dry Water’ or the ‘Great White Place’, Etosha is an apparently endless pan of silvery-white sand, upon which dust-devils play and mirages blur the horizon. As a game park, Etosha excels during the dry season when huge herds of animals can be seen amid some of the most startling and photogenic scenery in Africa. The roads are all navigable in a normal 2WD car, and the park was designed for visitors to drive themselves around. However, if you would prefer guided trips – or want an introductory guided tour in a safari vehicle – these can be organised both at camps and lodges within the park, and by the private lodges just outside (or consider instead one of the concession areas in Damaraland).

For most people, though, Etosha is a park to explore by yourself. Put a few drinks, a camera, extra memory cards and a pair of binoculars in your own car and go for a slow drive, stopping at the waterholes – it’s amazing. There are now five lodges and camps (confusingly all now known by NWR as ‘resorts’) within the park, as well as an ever-increasing number of lodges outside its boundaries.

Fish River Canyon

At 161km long, up to 27km wide, and almost 550m at its deepest, the Fish River Canyon is arguably second in size only to Arizona’s Grand Canyon – and is certainly one of Africa’s least-visited wonders. This means that, as you sit dangling your legs over the edge, drinking in the spectacle, you’re unlikely to have your visit spoiled by a coachload of tourists – at least, as long as you walk away from the main viewpoint. In fact, away from the busier seasons you may not see anyone around here at all!

Situated in a very arid region of Namibia, the Fish River is the only river within the country that usually has pools of water in its middle reaches during the dry season. Because of this, it was known to the peoples of the area during the early, middle and late Stone Ages. Numerous sites dating from as early as 50,000 years ago have been found within the canyon – mostly beside bends in the river. Around the beginning of this century, the Ai-Ais area was used as a base by the Germans in their war against the Namas. It was finally declared a national monument in 1962. Ai-Ais Restcamp was opened in 1971, though it has been fully rebuilt since then.

Kolmanskop

This ghost town, once the principal town of the local diamond industry, was abandoned over 60 years ago and now gives a fascinating insight into the area’s great diamond boom. Many of the buildings are left exactly as they were deserted, and now the surrounding dunes are gradually burying them. In its heyday, the town was home to over 300 adults and 44 children, and luxuries included a bowling alley, iced refrigerators and even a swimming pool. A few of the buildings, including the imposing concert hall, have been restored, but many are left exactly as they were deserted, and are gradually being buried by the surrounding dunes.

In a room adjacent to the concert hall, there is a simple café-style restaurant. Do make time to look at the photographs that adorn the walls, from early mining pictures to some chilling reminders of the far-reaching effects of Nazi Germany. A century since diamonds were first discovered here, it’s now possible to buy diamonds in the ‘Diamond Room’, with prices upwards from N$500. There’s also a display charting the history of the diamond boom and the people with whom it is inextricably linked.

Kwando River

The southern border of the eastern Zambezi Region is defined rather indistinctly along the line of the Kwando, the Linyanti and the Chobe rivers. These are actually the same river in different stages. The Kwando comes south from Angola, meets the Kalahari’s sands, and forms a swampy region of reedbeds and waterways called the Linyanti swamps. These swamps form the core of Nkasa Rupara National Park. In good years the Linyanti River emerges from here and flows northeast into Lake Liambezi, from where it flows out from the eastern side as the Chobe River. This beautiful river has a short course before it in turn is swallowed into the mighty Zambezi, which continues over the Victoria Falls, through Lake Kariba, and eventually discharges into the Indian Ocean in Mozambique.

To the west of the Kwando River, inside Bwabwata National Park’s Kwando Core Area, is a narrow tract of land that is wide in the north, but becomes narrower towards the Botswana border. Known variously as ‘the Triangle’, ‘the Susuwe Triangle’ or ‘the Golden Triangle’, it is rich in wildlife.

Bushmanland

To the east of Grootfontein lies the area known as Bushmanland. While it is today in the Otjozondjupa Region, Bushmanland is still what most people call the area. This almost rectangular region borders on Botswana and stretches 90km from north to south and about 200km from east to west. Drive east towards Tsumkwe, and you’re driving straight into the Kalahari. However, on their first trip here, people are often struck by just how green and vegetated it is, generally in contrast to their mental image of a ‘desert’.

In fact, the Kalahari isn’t a classic desert at all; it’s a fossil desert. It is an immense sand sheet which was once a desert, but now gets far too much rainfall to be classed as a desert. Look around you and you’ll realise that most of the Kalahari is covered in a thin, mixed bush with a fairly low canopy height, dotted with occasional larger trees. Beneath this is a fairly sparse ground-covering of smaller bushes, grasses and herbs. There are no spectacular sand dunes; you need to return west to the Namib for those! This is very poor agricultural land, but in the east of the region, especially south of Tsumkwe, there is a sprinkling of seasonal pans. Straddling the border itself are the Aha Hills, which rise abruptly from the gently rolling desert. This region, and especially the eastern side of it, is home to a large number of scattered Bushman villages of the Ju/’hoansi !Kung.

Related books

For more information, see our guides to Nambia:

Related articles

Namibia in Southwest Africa may be synonymous with gigantic dunes, world heritage sites like Namib Sand Sea and national parks teeming with wildlife but that shouldn’t overshadow the endless charm of the cosmopolitan capital Windhoek. Encircled by the glorious Auas Mountains to the east, and the Khomas Hochland Plateau to the west, Windhoek is a…

Marble caves, salt lakes and rainbow mountains.

Look at the stars, look how they shine for you.

We’ve scoured the African continent for the best sites to spot rhinos in the wild.

We’ve scoured the African continent for some of the best sites to get up close and personal with lions.

An insight into one of Namibia’s best-kept secrets

Nick Molloy gives us the lowdown on Namibia’s famous Skeleton Coast, where the shipwrecks leave you with no doubt as to the inspiration behind its name.