Take time to look beneath the surface in Sussex and you’ll find layers of difference, and it’s those qualities that make it infinitely rewarding to explore. I’m still finding new places within a few miles of my home in Lewes, having lived here for more than 20 years.

Tim Locke, author of Slow Travel Sussex: the Bradt Guide

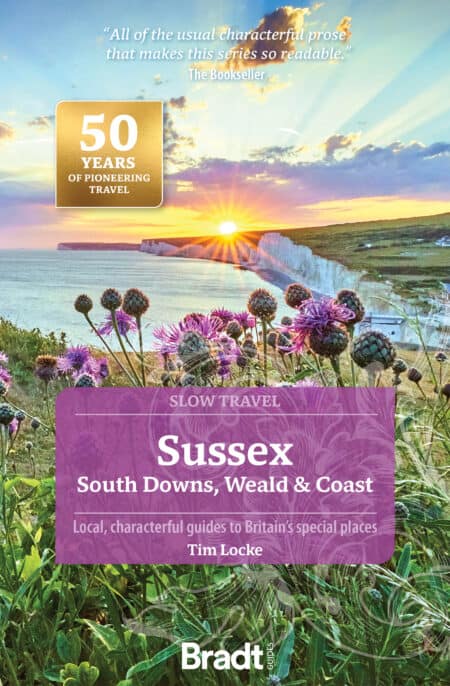

Sussex mingles the extremely familiar with the ridiculously unknown. There are scenes almost everyone recognises: the seafront at Brighton, Beachy Head and the Seven Sisters cliffs, Arundel Castle.

Then those undeniably Sussex-ish things that pop up all over the place: tile-hanging and weather-boarding, finger signposts in the middle of village greens, riverless valleys and chalky tracks in the South Downs, chunky-looking sheep, ploughed fields full of flints, crooked hawthorns bent by the wind.

On the map the coastal strip looks like one built-up conurbation, yet it’s full of nuances and surprises: a strange assemblage of defunct naval craft making up houseboats at Shoreham, for instance, or some Indian-looking dwellings in the shadow of the astonishingly forward-looking 1930s De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill. And those deep glens and sandstone cliffs east of Hastings, that look like a bit of transported Devon.

West and East Sussex are two very contrasting entities too: West is aristocratic – big estates like Petworth, Arundel and Goodwood. In the East, the High Weald is a very rare survival of a medieval landscape that in many respects has changed very little: a peasant economy and iron-producing area in times gone by.

Slow Travel Sussex pokes about the curios and doesn’t visit everywhere. That wouldn’t be possible or very useful. Instead I’ve made it an anthology of favourite places and experiences. That view through the oval cut-outs in the huge brick piers of the Ouse Valley Viaduct, for example.

Or the strange triple-towered ruin of Old Brambletye House, all by itself beside a muddy track, quite unannounced near Forest Row: I couldn’t find it again without a map. Or the surreal wander through the immensely ancient yew forest of Kingley Vale where nothing else grows under the woodland canopy and you’re transported into a world closer to Tolkien and Harry Potter than to the supposedly crowded Southeast.

Bradt on Britain – our Slow Travel approach

Bradt’s coverage of Britain’s regions makes ‘Slow Travel’ its focus. To us, Slow Travel means ditching the tourist ticklists – deciding not to try to see ‘too much’ – and instead taking time to get properly under the skin of a special region. You don’t have to travel at a snail’s pace: you just have to allow yourself to savour the moment, appreciate the local differences that create a sense of place, and celebrate its food, people and traditions.

For more information, check out our guide to Sussex

Food and drink in Sussex

It’s not hard to find high-quality locally produced food and drink in Sussex. On the coast, Hastings Old Town, for instance, has become a byword for fresh fish, and for fish and chips, and recent proliferation of farmers’ markets in virtually every town in Sussex and farm shops on nearly every other country lane has brought local food and its producers to the people. Food festivals have sprung up all over Sussex and there’s something food or drink-related somewhere in Sussex in every month of the year, including the Rye Bay Scallop Week in February and the Chilli Fiesta at West Dean College in early August, as well as various events in Brighton and Hove, Ardingly College, Lewes, Horsham and many other places.

A hundred years ago, pretty much every town in Sussex would have produced beer, with at least one brewery in operation, but things declined rapidly with takeovers by big breweries in the 1960s and 1970s. Harvey’s Brewery in Lewes managed to weather that particular storm and is very much flourishing. The head brewer, Miles Jenner Miles confesses to giving a daily prayer of thanks to the existence of the Campaign for Real Ale, without which many small breweries like this might have disappeared. And happily numerous other breweries have opened in recent decades, including Dark Star in Partridge Green and the Long Man Brewery based in Church Farm at Litlington in the Cuckmere Valley. Cider is produced in Sussex too, though not on the scale of the West Country; the best selection is found at Middle Farm, near Firle – where barrels are laid out in rows, according to sweetness.

A bigger story is Sussex’s upward surge as a wine producer, with a great number of vineyards appearing in the last couple of decades. The soil in places, particularly by the Downs, is similar to that of the Champagne region in France. And the Sussex vineyards such as Ridgeview and Bolney are producing some exceptionally classy stuff, winning the major awards and, as one wine seller told me ‘trouncing the French at their own game’. Rathfinny Wine Estate, just outside Alfriston, is set to become the biggest wine producer in Britain, but it’s all very much in its infancy at the time of writing.

When to visit Sussex

January

Wrap up warm & take the binoculars

Pulborough Brooks RSPB reserve is a shimmering wetland beauty, and at this time of year huge numbers of wintering birds make an appearance: wigeons, shovellers, Bewick’s swans and mallards are much in evidence and you might spot peregrines, hen harriers and barn owls hunting from the skies.

Black-tailed godwits and wigeon at Pulborough Brooks © Anne Harwood

Black-tailed godwits and wigeon at Pulborough Brooks © Anne Harwood

February

Tuck in at Rye

Rye’s week-long Scallop Festival is a major fixture on the Sussex culinary calendar, when this gorgeous medieval town’s profusion of restaurants offer all sorts of scallop-themed dishes, and there are tasting events, live music and cooking demonstrations.

March

Follow Pooh’s footsteps to the North Pole & Heffalump Trap

Wander in the wilds of Ashdown Forest and get happily lost on the heathy heights, where the Winnie-the-Pooh stories were set, and have a game of Poohsticks at the instantly recognisable Poohsticks Bridge.

April

Arty treasures

Head over to Chichester to see who’s being exhibited at the Pallant House Gallery, or seek out the Ravilious paintings at Eastbourne’s Towner Gallery.

Browsing through Pallant House Gallery © Pallant House Gallery

Browsing through Pallant House Gallery © Pallant House Gallery

May

Garden glory in late spring

You’re spoilt for choice, with some world-class gardens. For starters, though we know we’ve left some brilliant ones out: Nymans, Sheffield Park, Wakehurst Place, High Beeches, Great Dixter, Borde Hill, West Dean and Woolbeding Gardens.

June

Meet the county set

Ardingly’s showground hosts the three-day South of England Show: heavy horses, livestock displays, equestrian events, hound events and large dollops of local colour.

July

Take in one of Sussex’s great outdoor museums

There’s plenty happening at the Amberley Museum and Weald, where craftspeople demonstrate all manner of bygone industrial activities. Also visit the Weald and Downland Museum, with its re-erected historic buildings from all over the Southeast and where you can sign up to courses on a wide range of rural matters.

One man went to mow, went to mow a meadow © Weald & Downland Open Air Museum

One man went to mow, went to mow a meadow © Weald & Downland Open Air Museum

August

Cycle to the beach

Beat the crowds and take the cycle paths to Sussex’s best sandy beaches: from Chichester southwards to West Wittering and from Rye to Camber Sands.

Perfect sands can be enjoyed at West Wittering © West Sussex Weekends

Perfect sands can be enjoyed at West Wittering © West Sussex Weekends

September

Rockpools & cliffs

Browse the rockpools at Cuckmere Haven and head up the Seven Sisters for the finest cliff walk in the Southeast. Stop for a drink at the Tiger in East Dean and walk back through Friston Forest.

October

No need to go to New England when you’ve got this

Autumn colours at Sheffield Park are quite something as the maples, tupelo trees, birches, eucryphias and swamp cypresses combine to make a spectacular show, enhanced by the reflections in the lakes. Lots of visitors, and the car park fills up; but you can come by steam train on the Bluebell Railway from East Grinstead or by bus from Brighton, Lewes, Haywards Heath or Burgess Hill.

November

Bonfire Night, Sussex-style

Lewes’s ear-shattering 5 November celebrations feature huge torch-lit parades in fancy dress, marching bands, a burning tar barrel race and huge effigies of Guy Fawkes, politicians and others who are ceremonially blown up at various firework displays all around town. And it’s not just in Lewes: throughout autumn (from September onwards) various towns in East Sussex have their own similar celebrations.

A man photographs the bonfire in Lewes © Mitotico, Shutterstock

A man photographs the bonfire in Lewes © Mitotico, Shutterstock

December

Royal exotica

Take a pre-Christmas trip to Brighton’s Royal Pavilion: Indian fantasy outside, Chinoiserie to the nth degree inside. You’ll hardly believe your eyes. Then hire skates and try out the seasonal ice rink in front of the Pavilion.

What to see and do in Sussex

Brighton Pavilion © Dmitry Naumov, Dreamstime

Brighton Pavilion © Dmitry Naumov, Dreamstime

Brighton & its hinterlands

The most densely populated strip of coast in the southeast is a proverbial mixed bag, and it’s not an area in which you are promised sense of place wherever you go. But Brighton and Hove, as they are jointly called nowadays, celebrate being different with great aplomb, and there’s much pleasure picking one’s way through their less likely-looking further reaches as well as the more trumpeted aspects of one of the country’s most rewarding seaside resorts.

Connoisseurs of local museums should beat a path to Worthing, Hove and Brighton, which together have a notable trio. Worthing’s archaeology and costume stand out; Hove’s has a great tearoom after you’ve perused the very early silent films of the ‘Hove pioneers’. Brighton’s, as you’d expect, is wonderfully eclectic. For complete unexpected quirkiness, Shoreham takes some beating with its Art Deco airport, Norman church architecture, maritime/local history museum and jaw-dropping assemblage of houseboats.

Inland are some of the most visited parts of the South Downs: Ditchling Beacon and Devil’s Dyke get the crowds, but you may prefer to walk over to the Chattri War Memorial, Cissbury’s prehistoric ramparts and flint mines or Jack and Jill Windmills, or to savour the immediate sense of tranquillity found in those innumerable folds in the landscape. Ditchling’s imaginatively revamped museum explores a variety of changing art-related themes; the village was home to a notable colony of craftspeople in the early 20th century. Steyning is a town with plenty of Slow attributes, and is handily placed for walks up to Chanctonbury Ring, one of those rare features on the Downs that are identifiable from a distance.

Further north, the Low Weald has some notable moments, with the headquarters of the Sussex Wildlife Trust at Woods Mill and the Downs Link cycle route heading north to Surrey. In the far north of the area covered by this chapter, Horsham has some lovely streetscapes around its church, and Tilgate Park is a rewarding strolling ground on the peripheries of Crawley.

Arundel’s impressive castle © West Sussex Council

Arundel’s impressive castle © West Sussex Council

Chichester Harbour to the Arun

It’s easy to have a soft spot for Kingley Vale, the mysterious yew forest on the Downs. No one knows why it’s there, and it’s enough of a trek to mean that only the most dedicated get to it. From the top, the view is utterly sublime, far over Chichester Harbour, Sussex’s answer to East Anglia – a lowland of great water channels and saltmarshes. This waterscape could hardly be more different from the South Downs, and makes best sense explored by boat; you might particularly like the solar-powered catamaran that glides silently and slowly around the harbour – the perfect way of slowing down.

At its northern end, Chichester is one of a quartet of sharply contrasting historic centres in this corner of Sussex, which along with Midhurst, Petworth and Arundel all have their special places to savour – the Bishop’s Palace Gardens forming an unexpected haven in the heart of Chichester, Midhurst with its melodramatic Cowdray Ruins, Petworth for its juxtaposition with a huge park and house, and Arundel, where you can swim in a lido with a view of the castle or encounter the wildlife at the Wetland Centre.

Art is particularly strong here, with Pallant House at Chichester being one of the country’s top modern art collections, and the Cass Foundation’s contemporary sculpture park in the heart of the Goodwood Estate being one of the most magical. Petworth House has the foremost art collection of any National Trust house – though for me the Grinling Gibbons carvings steal the show. Stansted Park and Uppark are fascinating houses to visit and compare, each destroyed by fire and rebuilt at either end of the 20th century. And more ancient offerings are there in the form of exceptional mosaics at Bignor Roman Villa and Fishbourne Roman Palace, and a host of the churches with medieval wall paintings, such as at Clayton, Hardham and Trotton.

At Loxwood and Chichester you can travel slowly by canal boat on a short cruise along canals being rescued by volunteers. The same spirit of voluntary dedication has gone wholeheartedly into two fine rural museums – the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum at Singleton, and the Amberley Museum; both are in choice settings in the South Downs, with plenty else to justify staying and exploring the area. Amberley village is a picture of perfection with its thatched houses and views across the Wild Brooks, part of a watermeadows wetland that merges into Pulborough Brooks RSPB reserve.

Walking on the Downs escarpment is boosted by some glorious greens and countryside immediately north – as at Bignor for instance. But if there’s a favourite view here, it is further north, in the High Weald, from the heights of Black Down or from the obscurity of Woolbeding Common, where you look to the Downs across a foreground of heather – a scene that almost appears too wild to be in Sussex.

In 2016 a sensational archaeological discovery was made in this much-wooded part of the Sussex Downs, between the Hampshire border and the Arun, following a two-year period of research. The thick tree cover had for centuries covered up history’s secrets, but with the help of Lidar technology – which uses an aircraft-mounted laser-guided beam that can penetrate through tree cover – a huge system of agricultural fields was revealed, dating from around 1500bc, extending across some 600 square miles. The forest had protected features over the centuries; in East Sussex anything like this would have long ago been obliterated in the more open landscape. And it wasn’t just a patch here and a patch there, but a continuous area of former cultivation: previously it had been thought that large-scale farming had begun with the advent of the Romans, but this find took the story back many centuries earlier. The evidence points to a scale of agriculture so vast that the society must have been organised on the lines of a farming collective. So prehistoric does not necessarily equate to primitive.

Camber Sands © Visit England

Camber Sands © Visit England

Eastbourne, Hastings & 1066 Country

Where the South Downs end at Beachy Head, a stretch of coast extends eastwards to the Kent border, comprising the most diverse seaboard in Sussex. Take a boat cruise from Eastbourne and stroll its gorgeous Victorian pier, tuck into fish and chips by the net houses of Hastings Old Town after an exhilarating walk over the adjacent sandstone cliffs, wander through the cobbled streets of Rye and cycle your way along the unheralded coastline west of Bexhill’s astonishing 1930s De La Warr Pavilion.

This region has numerous reminders of invasions both threatened and actual. Most famously it was the landing point of the Normans in 1066 in the last successful invasion of the mainland, from which they went on to defeat the English at what is now called Battle and change the course of English history. Then in medieval times it was a confederation of wealthy ports supplying naval craft and men to the monarch in return for certain privileges, including tax exemption and legal jurisdiction over criminals. These Sussex and Kent towns were known as the Cinque Ports, which originally numbered five, but the list later grew to include Hastings, Rye and Winchelsea.

The area is instilled with a potent sense of the past, with Normans in evidence at Pevensey Castle (originally Roman) and Battle Abbey, and magnificent moated castles at Herstmonceux and Bodiam – the latter reached by the Kent and East Sussex Railway, and easily visited in conjunction with Great Dixter, the great 20th-century horticultural creation of Christopher Lloyd. Camber Sands is by far the premier beach in East Sussex, and a bike ride away from Rye. Some former coastal settlements now stand well inland as the sea has silted up over the centuries, leaving areas of rich, marshy farmland that have a quiet, brooding beauty – seen at its best around Rye Harbour nature reserve, the Royal Military Canal between Winchelsea and Cliff End and the Pevensey Levels.

The High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty extends across part of this area, including Bodiam, Great Dixter, Battle and Hastings.

Cuckmere Haven © South Downs National Park Authority

Cuckmere Haven © South Downs National Park Authority

Lewes down to Beachy Head

Sussex’s most sublime stretch of coast is within this small chunk of the South Downs, comprising the cliffs between Seaford and Eastbourne. But it’s a relatively brief affair; if there’s one place above all that needs to be savoured slowly, this is it – browsing a rockpool at Cuckmere Haven, munching a sandwich and spotting Bronze-Age flints on turf clifftops, or drinking in the view of the wavy profile of the Seven Sisters from Seaford Head. Westwards, a huge shingle beach lines the low-lying coast all the way to Newhaven, a clean and inviting sweep of shore that makes one of the best swimming spots hereabouts.

Inland, the Downs have some really quiet moments: even though this is one of the most thoroughly thumbed parts of the national park, there is plenty for escapists. The ever-nasty but useful A27 disappears from view and earshot completely as you ascend into the world of skylarks either side of the Cuckmere Valley near Alfriston; the South Downs Way encounters a primeval moment above the enigmatic Long Man of Wilmington, Britain’s tallest chalk hill figure above the head of Deep Dean, a secretive dry valley unaltered by modern agriculture, its slopes too steep for the plough.

Lewes gets a trickle of canny tourists but apart from the spectacular exception of bonfire night in November is never particularly overrun. Sloping, neighbourly, enticing, nonconformist, ancient, distinctive – it suggests plenty of adjectives. I one favourite landmark view had to be singled out then it is the prospect down School Hill, past Harvey’s Brewery with its periodic malty aroma wafting over passing shoppers, to the Downs above. Art and music are big in the vicinity: many musicians working at Glyndebourne Opera House are based in town or around, and opera-goers often stay over and discover the town’s many pleasures. Lewes also makes an obvious base for those on the trail of Virginia Woolf, who lived nearby at Monk’s House in Rodmell, and her bohemian sister Vanessa Bell and her entourage at Charleston near the estate village of Firle. Anyone keen on the Charleston set should also beat a path to Farley Farm House at Muddles Green for one of the entertaining and erudite Sunday tours of the former house of surrealist painter Roland Penrose and the photographer Lee Miller, where Picasso once visited.

Bluebells in Ashdown Forest © Ashdown Forest

Bluebells in Ashdown Forest © Ashdown Forest

The Western High Weald

East Sussex doesn’t geographically extend north to south for any great distance, but this northern strip of sandstone scenery feels a world away from the more visited South Downs and coast. You need to get high up to piece together this remote-feeling and strangely impenetrable landscape of copses, hammer ponds, larger woodlands and sandstone outcrops. From churchyards such as those at Turners Hill, West Hoathly and Cuckfield you look over the tree tops towards the South Downs, bare-sloped and orderly.

You can get similarly grand views from some of the big estates that harbour world-class gardens such as Standen – a favourite Arts and Crafts house open to public view – and Borde Hill. Other great horticultural creations are more tucked away and secretive. Come here in late spring or early summer and the rhododendrons and azaleas put on a dazzling show. Nymans perhaps outdoes them all for sheer theatricality. Wakehurst Place and Sheffield Park are two vast and justifiably famed National Trust gardens. The latter, also celebrated for its stupendous autumn foliage, is most memorably reached by a vintage steam train on the Bluebell Railway. Among other architectural hallmarks, Horsham slates, hipped gables, medieval ‘Wealden halls’, pantiles and timber frames are seen in a plethora of ancient buildings in numerous villages – among them Mayfield, Wadhurst, Burwash and Rotherfield.

The term ‘High Weald’ isn’t widely understood, even by some of its own residents. The High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty is defined by its geology (sandstone, laid down during the dinosaur era 130 million years ago as what are known as the Hastings Beds) rather than its altitude. It’s a rough triangle of land spilling into Kent and extending from just outside Horsham in the west to Hastings and Rye in the east, and bounded on its north side by the peripheries of East Grinstead, Tunbridge Wells and Tenterden. It was never an area of aristocratic estates or rich farmland, unlike West Sussex: iron ore extraction and smelting, seasonal swine grazing, and woodland activities such as charcoal making and forestry were more the norm in medieval times in this less fertile terrain, and the area has essentially changed its look very little in 700 years – effectively a rare survival of a medieval landscape.

The High Weald has numerous identifying features. Much of the tree cover is ancient woodland, preserving archaeological features such as raised boundary banks and charcoal-burning platforms. These wildlife-rich areas of woodland and the numerous unimproved meadows are found far more commonly than across the rest of the country: 70% of woodland in the High Weald is classified as ancient (that is, in existence at least since 1600), as compared to just 19% across the whole of Britain: ferns and wild garlic are ancient woodland indicators. Oaks are the predominant tree species. Here and there you’ll find ‘gills’ – steep-sided, fast-flowing streams carving out a course through ravines – the only area in southeast England that they exist. Fields often tend to be small and irregularly shaped – the result of peasants hacking out by hand little clearings in the Wealden forest. It wasn’t a rich area, but somewhere folk eked out a rudimentary life grazing pigs or harvesting from the forest.

Parts of this area have a distinctly un-Sussex look. Ashdown Forest is a large lowland heath that has almost a moorland character, carefully preserved by conservators for many years and almost a mini national park in itself. Wandering deer stray on to the lonely roads, clumps of Scots pines punctuate a skyline that might be in northern England, and Winnie-the-Pooh aficionados tackle a daunting maze of paths in search of literary landmarks. Further east Eridge Rocks is one among several rock outcrops in the vicinity that wouldn’t look too out of place in the Peak District, although the luxuriant growths of bamboo hint at something more exotic.

The Western High Weald

East Sussex doesn’t geographically extend north to south for any great distance, but this northern strip of sandstone scenery feels a world away from the more visited South Downs and coast. You need to get high up to piece together this remote-feeling and strangely impenetrable landscape of copses, hammer ponds, larger woodlands and sandstone outcrops. From churchyards such as those at Turners Hill, West Hoathly and Cuckfield you look over the tree tops towards the South Downs, bare-sloped and orderly.

You can get similarly grand views from some of the big estates that harbour world-class gardens such as Standen – a favourite Arts and Crafts house open to public view – and Borde Hill. Other great horticultural creations are more tucked away and secretive. Come here in late spring or early summer and the rhododendrons and azaleas put on a dazzling show. Nymans perhaps outdoes them all for sheer theatricality. Wakehurst Place and Sheffield Park are two vast and justifiably famed National Trust gardens. The latter, also celebrated for its stupendous autumn foliage, is most memorably reached by a vintage steam train on the Bluebell Railway. Among other architectural hallmarks, Horsham slates, hipped gables, medieval ‘Wealden halls’, pantiles and timber frames are seen in a plethora of ancient buildings in numerous villages – among them Mayfield, Wadhurst, Burwash and Rotherfield.

The term ‘High Weald’ isn’t widely understood, even by some of its own residents. The High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty is defined by its geology (sandstone, laid down during the dinosaur era 130 million years ago as what are known as the Hastings Beds) rather than its altitude. It’s a rough triangle of land spilling into Kent and extending from just outside Horsham in the west to Hastings and Rye in the east, and bounded on its north side by the peripheries of East Grinstead, Tunbridge Wells and Tenterden. It was never an area of aristocratic estates or rich farmland, unlike West Sussex: iron ore extraction and smelting, seasonal swine grazing, and woodland activities such as charcoal making and forestry were more the norm in medieval times in this less fertile terrain, and the area has essentially changed its look very little in 700 years – effectively a rare survival of a medieval landscape.

The High Weald has numerous identifying features. Much of the tree cover is ancient woodland, preserving archaeological features such as raised boundary banks and charcoal-burning platforms. These wildlife-rich areas of woodland and the numerous unimproved meadows are found far more commonly than across the rest of the country: 70% of woodland in the High Weald is classified as ancient (that is, in existence at least since 1600), as compared to just 19% across the whole of Britain: ferns and wild garlic are ancient woodland indicators. Oaks are the predominant tree species. Here and there you’ll find ‘gills’ – steep-sided, fast-flowing streams carving out a course through ravines – the only area in southeast England that they exist. Fields often tend to be small and irregularly shaped – the result of peasants hacking out by hand little clearings in the Wealden forest. It wasn’t a rich area, but somewhere folk eked out a rudimentary life grazing pigs or harvesting from the forest.

Parts of this area have a distinctly un-Sussex look. Ashdown Forest is a large lowland heath that has almost a moorland character, carefully preserved by conservators for many years and almost a mini national park in itself. Wandering deer stray on to the lonely roads, clumps of Scots pines punctuate a skyline that might be in northern England, and Winnie-the-Pooh aficionados tackle a daunting maze of paths in search of literary landmarks. Further east Eridge Rocks is one among several rock outcrops in the vicinity that wouldn’t look too out of place in the Peak District, although the luxuriant growths of bamboo hint at something more exotic.

Related books

For more inforamtion, see our guide to Sussex:

Related articles

From medieval castles to Edwardian Arts-and-Crafts architecture.

Ideal for picking up some produce for a picnic or a family day out.

These are some of our favourite green spaces to wander in England.

Some people go to church, others go to churches.