It is also a place too often overlooked, forgotten about as we turn our attentions (and tourist dollars) to its better developed and more familiar neighbours. As long as we do this, it is we who are missing out.

Sophie and Max Lovell-Hoare authors of South Sudan: The Bradt Guide

South Sudan, in the two years after achieving independence, is still in the midst of tremendous change: the war with the North may be over, but internal rivalries continue to risk tearing the country apart yet again.

Those visitors who are both determined and adventurous can, however, still immerse themselves in the beauty and diversity of this remarkable country. From the hectic energy of Juba, the world’s youngest capital, to fascinating Dinka cattle camps and traditional wrestling in Bor, South Sudan offers an incredible variety of experiences.

Explore the biodiversity of its five national parks to capture a glimpse of the elusive ‘Big Five’ and see for yourself why this country has been called ‘the lost heart of Africa’.

Please note There has been a serious deterioration in security in South Sudan since these pages were compiled, and some of the practical information here will now be out of date. In particular, many areas are currently not safe to travel. You are advised to contact your embassy and local agents prior to travelling.

For more information, check out our guide to South Sudan

Food and drink in South Sudan

Food

You won’t go hungry in South Sudan. Numerous cuisines are available and the ubiquitous Ethiopian dishes are particularly tasty. The standard of hygiene during food preparation seems to be high, both in restaurants and in people’s homes, so we were happy and healthy eating everything from hotel buffets to deep-fried streetside snacks. South Sudan cuisine is unsophisticated; the staples are bread, pancakes and porridge made from corn, sorghum, maize and other grains. Look out in particular for kisra, a wide, flat bread made from fermented sorghum flour; gurassa, a thick corn bread; and brown wheat poshto.

A wide range of vegetables and pulses are available in the marketplace, many of them grown locally. In addition to potatoes, sweet potatoes, daal (lentils) and peas, you’ll find bamia (okra or ‘ladies fingers’), ful (mashed fava beans) and local specialities such as kudra (a leafy green vegetable rich in vitamins A and C), dodo (amaranth leaves), and pea leaves. Onions, tomatoes, peppers, cabbages, plantain bananas, cassava and carrots are imported from Uganda and Kenya.

During mango season (March), you won’t be able to move for sweet, ripe mangoes and will happily be able to gorge yourself on them at rock-bottom prices. Each green mango hangs pendulously from the tree like a giant, round Christmas tree decoration, and when the fruits ripen, fall and bounce across the tin roofs, it can sound as if the sky is falling in. The markets also sell juicy pineapples, papayas (pawpaw) and oranges, apples, guava and avocados, although many of these are imported from neighbouring countries. Don’t miss sugarcane and sorghum stems: their juice is immensely sticky and sweet and chewing on them is a popular snack. Many types of foods are fried in cow brain rather than cooking fat as it gives a distinctive flavour and vegetarians should be aware that this applies as much to vegetables and pulses as to fish and meat.

Meat (usually mutton or goat) is typically boiled or stewed, which helps to make it less tough, and it can be served with spices and peanut or simsim (sesame) sauce to add flavour. Dried or smoked beef is often eaten with peanut or groundnut sauce and may be made into a stew with bamia. A small amount of chicken is included in the diet, whilst pork is rarer as it has to be imported. Some communities eat fish from the rivers and swamps, and dried fish is oft en added to kajaik (a popular type of stew) or to aseeda (sorghum porridge) to give added flavour. A popular roadside snack is rolled eggs. There are relatively few desserts and sweets in South Sudan, although if you find them it is definitely worth trying the delicious, chewy macaroons made from peanuts, known locally as ful Sudani.

Eating out

South Sudan’s cities are full of small, cheap canteens selling local food as well as Eritrean, Ugandan and, occasionally, Kenyan cuisine. One set of dishes is prepared at a time, so you’re unlikely to be given a choice about what to eat. Food is served on large, metal trays: both the bread and the different meats, vegetables and pulses are dished up side by side, much like an Indian thali, and as many as six people will eat from a single tray. Dishes are typically meat-based or cooked with meat products, so vegetarians will have to keep their wits about them, particularly in smaller establishments.

You will find a wider range of food only in Juba, where prices are also significantly higher. The hotel restaurants cater primarily to expats and will readily cook up a hamburger, spaghetti bolognese or similar but it won’t be cordon bleu and you will certainly pay for the privilege. Anything that includes imported ingredients (so in reality most things you would want to eat) will be expensive.

Drinks

Beer is sold in bars and shops across South Sudan. Southern Sudan Breweries Ltd produces three beers – White Bull, Club Pilsener and Nile Special – under licence at their brewery in Juba, and other East African beers, such as Tusker Lager, are also popular. Heineken, Carlsberg and Skol are all imported, with inevitably inflated price tags, but tend to only be available in Juba. If you value your eyesight, try to avoid the appropriately named Siko, which is a locally made gin that tastes something akin to white spirit. Although numerous slum dwellers swear by it, there’s no guarantee it won’t make you go blind or worse.

Bottled soft drinks are widely available. The biggest-selling products are the locally manufactured Club Minerals sodas, though Coca-Cola, Pepsi and even Red Bull are also popular among those who can afford to buy them. There are two local brands of bottled water, Aqua’na and Jit, as well as imported alternatives. All the bottled water brands should be safe to drink, but it’s always worth checking the cap to make sure it hasn’t been tampered with to disguise a refill from the tap. Sudanese coffee is served from a jebena, a tin jug with a long spout that slightly resembles a watering can, albeit in miniature. The coffee is served sweet, often spiced with ginger or cinnamon, and comes in tiny cups or glasses. Black, fruit and herbal teas, in particular kakaday (hibiscus tea) are also popular and, as the water has been boiled, usually considered safe to drink. You’ll see numerous old men whiling away the hours, tea cup in hand, sitting on street corners, at bus stops and in parks

Health and safety in South Sudan

Health

South Sudan has one of the poorest health systems in the world: less than a decade ago there were just four hospitals and three surgeons in the entire country. Life expectancy for both men and women is about 62 years and South Sudan’s infant mortality (defined as children dying before their first birthday) is the 19th worst in the world. Doctors and nurses are in desperately short supply, and those hospitals and clinics that do exist are underequipped and lacking in drugs. They are frequently without water and electricity as well. If you fall seriously ill or have an accident in South Sudan, you will need to arrange MedEvac to Nairobi or Kampala for treatment. For this reason, comprehensive travel insurance is imperative. Do not get on a plane without it.

Vaccinations

Your GP or a specialised travel clinic will be able to check your immunisation status and advise you of any additional inoculations you may need. You should make an appointment at least six weeks before you intend to travel, as some vaccinations require you to have a series of injections over a protracted period. If you are travelling with children under 16 then at least eight weeks is needed to complete some courses. Visitors to South Sudan are advised to make sure they have up-to-date protection against tetanus, polio and diphtheria (now given as an all-in-one vaccine), typhoid, hepatitis A and yellow fever. Immunisations against meningococcal meningitis, hepatitis B and rabies are also highly recommended.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

South Sudan is not a safe country in which to travel. The UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) advises against all travel within 40km of the border with the Republic of Sudan and to all but essential travel to Wau. Armed clashes between the army and civilians are a regular occurrence, and there is an ongoing threat of cross-border raids. The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) is thought to have been responsible for a number of attacks on villages in Western Equatoria in 2010, which resulted in a small number of fatalities. Crime levels are increasing in Juba as the city grows. Consular departments have recently recorded a number of incidents in which foreigners were mugged, including by assailants on the back of motorcycles, and they advise against going out alone, particularly at night.

There is a high security presence comprising police, soldiers and private security contractors, though these typically cause more of an irritation than a danger. Survival guides typically tell you what to do once you’re neck-deep in the brown stuff . This isn’t a smart position to be in. Avoiding getting into trouble in the first place is infinitely preferable, and preparation is the key. Using reliable information sources, establish where you’re going, how you’re going to get there and how you’re going to get back and impart this information to someone you trust. Always have a plan B. Keep your eyes and ears open and be flexible: choosing to change your plan in light of new information is much better than being forced to change it on the hop when circumstances conspire against you. Also, listen to your gut: evolution has given you the ‘hunch’ for a reason.

Female travellers

Traditional Sudanese families are very much divided along gender lines, and this influences everything from the tasks people do to who they meet with, where they sit in the home, and what they eat. Whilst foreign women are often considered ‘honorary men’ and may be given the option to move between these male- and female-dominated spheres, foreign men are unlikely to be able to do so.

The vast majority of women travellers have favourable impressions of the country, and it is generally considered safe for single women. The threat of crime and physical harassment are relatively low, particularly compared with neighbouring countries, and South Sudanese (both men and women) will often go out of their way to help a woman travelling on her own. That said, you should take the usual precautions: travel with a companion wherever possible, make sure that you are not out late at night, and dress in a manner that does not attract undue attention. If you feel uncomfortable in a situation, leave quickly and if possible head for a well-populated place: cafés, hotels and bus stations are ideal.

One area that does have potential pitfalls for women is the cheapest end of the accommodation market. Lokandas are based on communal sleeping arrangements, so the arrival of a female traveller (even one with a male companion) can sometimes provide managers with a headache as they wonder where they are going to put you.

Most tend to have smaller separate rooms that you will be offered, though if none are available you may be turned away. Women travellers should be sure to bring sufficient supplies of oral contraceptives, tampons, sanitary towels and any other personal items with them as these are unlikely to be available locally. You may also consider packing anti-thrush tablets or cream as fungal infections are particularly common (and uncomfortable) in South Sudan’s humid climate.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality is illegal in South Sudan and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community faces serious and continued discrimination. In 2008, the interim Government of Southern Sudan adopted its own penal code, which prohibits ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’. Consensual sex between two men carries a penalty of up to ten years. According to President Salva Kiir, speaking to Dutch radio in 2010, homosexuality is not in the ‘character’ of Southern Sudanese people, it does not exist in the country, and if anyone tries to import it, it will always be condemned. As you might imagine, the president is sadly not alone in holding these views, and homosexuals in South Sudan must be exceptionally discreet in order to preserve their lives and liberty. There are no public LGBT organisations and no gay scene. If you are travelling in South Sudan with a same-sex partner you are strongly advised to refrain from public displays of affection (although two men holding hands is seen as perfectly normal and acceptable) and to be circumspect when discussing your relationship with others. In general it is better to leave them with the impression that you are simply travelling with a friend.

Travel and visas in South Sudan

Visas

All foreigners visiting South Sudan require a visa. These are not available on arrival at the land borders, so you will need to get one from a consular department before departure. Even if you are arriving in Juba by air and can theoretically get a visa on arrival, it is still recommended that you apply for and collect your visa in advance in case for some reason your application is rejected and you are turned back at immigration. The cost of your visa and the application process depends on your nationality and the country where you are applying. You will therefore need to contact the embassy you will be using to establish the exact fee you will have to pay: for comparison purposes, a British national applying for a single-entry visa in London will pay £35, but if they apply in Washington, DC then they pay US$100. Visas for US nationals are particularly expensive and a US passport holder will pay US$160 for the visa in Washington.

Getting there and away

By air

The majority of visitors arrive in South Sudan by air, landing at the grandly named but less grandly equipped International Airport in Juba, and this is by far and away the easiest option for getting in and out of the country. That said, there are currently no direct flights from Europe or the US so you will have to plan your route accordingly, flying via the Middle East or an African hub such as Nairobi, Kampala or Addis Ababa. A number of the airlines listed here (including all of those registered in Sudan) are not permitted to fly in European airspace due to their poor safety records. With the exceptions of Egypt Air and Gulf Air, planes serving South Sudan are often old and poorly maintained. A civilian aircraft said to be an Antonov crashed in the Nuba Mountains in August 2012 killing all 32 people on board, and there have been a number of similar incidents in recent years.

By land

There are a large number of road border crossing points at which it would in theory be possible to pass into South Sudan. In practice, however, at the time of writing the vast majority of these border crossings are either closed entirely, or closed to foreigners. More border crossing details are given below, and the Ugandan crossing is currently your best bet. South Sudan’s borders are in many places unstable, with frequent outbursts of inter-ethnic violence as well as military crackdowns, so this should also be kept in mind. You should not attempt to cross into or out of South Sudan at any unofficial border crossing. Not only is it illegal, but such areas are often heavily mined and you risk being shot.

By boat

The Nile is navigable as far south as Juba, so it is theoretically possible to enter the country by barge and even the occasional steamer from the White Nile port of Kosti in the Republic of Sudan. This was once part of the popular Cairo to Cape Town overland route, and in time could even become a romantic cruise, but for now it is a trip for only the hardiest and most determined of travellers. With a stop at Malakal the journey takes approximately ten days, or half that time if you are travelling from Juba to Kosti due to direction of the water flow.

Transport is on the 50m-long cargo barges that travel up and down the river, which are tied together and pulled by a tug boat. There is no set timetable for departures or arrivals, you leave when the boat is ready and arrive whenever it gets there. The exact journey time is dictated by the weight and type of the cargo, the number of stops and the water level of the river. Any breakdowns (a common occurrence given the age and state of repair of the boats) will inevitably add to the journey time.

There are no cabins on the tugs and food is in short supply. Bring your own sleeping mat and mosquito net (to avoid being eaten alive), and plenty of fruit, tinned goods and biscuits. You will also need to bring bottled water or, at the very least, water purification tablets as all water on board is drawn straight from the Nile. At the time of writing it was possible to buy a one-way barge ticket from Kosti to Malakal for SDG35 and to Juba for SDG80. If you wish to travel ‘first class’, which essentially equates to a space on the roof of the tug rather than on the deck, it’ll set you back SDG100.

Getting around

South Sudan is a tough country to get around. It is large, similar in size to Afghanistan or Ukraine, but almost entirely lacking the infrastructure required to get from A to B due to the years of civil war and underinvestment. Some cities have no tarmacked road links and others are cut off entirely during the rainy season, meaning that the only way to reach them is by air. Poor security in some areas also makes driving unfeasible for foreigners.

By air

South Sudan has a small commercial air network that is largely operated by Kush Airlines. The airline’s hub is Juba and it operates regular services to Aweil, Bentiu, Malakal, Rumbek and Wau. The cost for each of these routes is around US$180 each way, with the exception of Malakal, where tickets start from US$250 one way and US$450 return. The UN operates regular flights to all parts of South Sudan, although tickets on these are usually only available to UN, embassy and NGO staff. If the flight is not full, however, and you ask the right person to book a seat for you, then you may be in luck. It is also possible to charter small planes, and this is typically how the tour operators move clients from Juba to the national parks. To enquire about the terms and costs of charter flights, you should contact the travel agents in Juba.

By road

At the time of writing, South Sudan had just a little over 400km of paved road. And in places, the term ‘paved’ seems a little optimistic. Road travel in the country, with the exception of the recently completed stretch between Nimule and Juba, is typically slow and backbreaking. Rainfall can make already bad roads even worse (sometimes impassable) and poor security in some areas (most obviously between Rumbek and Wau, in northern Jonglei, and anywhere close to the border with Sudan) means that it is not advisable for foreigners to drive or be driven.

Bus

South Sudan has a large range of transport options falling under the loose category of ‘bus’. At the top end of the scale you’ll find small coaches (some of them almost comfortable) in Juba, although many of these are owned by companies or NGOs and used solely for moving their staff around. There are also a few companies operating long-distance buses to Kampala: look out for the names LOL, Baby and Bakulu. Regular buses ply a few set routes, but are much slower and have a more relaxed attitude to squeezing in passengers. You can certainly forget about having your own dedicated seat.

These buses may be signed only in Arabic, and many of them appear to have a coach body attached to a truck chassis. Outside Juba you’ll also find trucks masquerading as buses: seats are welded in the back, and the sides are open to the elements. Built to last, with little consideration for speed or comfort, they are the cheapest – and often the only – option available.

Passengers and their worldly goods are crammed inside, while enough baggage is lashed on top to double the vehicle’s height. Minibuses (hafla) link towns that are relatively close together, and are a fast and convenient mode of transport. There’s no need to pre-book – just turn up at the bus station and the minibus departs when full. You’ll need to wait patiently, often for several hours, before the minibus leaves but it’s an ideal opportunity to get a bowl of ful or a kebab, and to chat with the ubiquitous tea ladies at their stalls.

Boksi

The workhorse of rural South Sudan is the pick-up truck, known locally as a boksi (plural bokasi). Almost always a Toyota Hilux, these are the most common form of transport where there is no sealed road. Quicker than a bus covering the same ground, and often the only option, they are also slightly more expensive. Bokasi are a (relatively) fast and furious way to travel. The cab has two seats next to the driver and the covered back of the pick-up has bench seating along each side, with five passengers crammed on each row. Any free floor space is taken up with baggage, and with an unlimited number of children thrown in for good measure. Latecomers sit on the roof. The benches are hard and you can feel every bump. If you can, avoid the space over the tailgate – whenever the vehicle hits a pot-hole you’ll be liable to go flying. Short trips are fine, but a long journey can leave you cramped and bruised if the road is particularly bad. The more comfortable seats next to the driver cost a quarter to a third more than those in the back and are always the first to be reserved.

Self-drive

A few visitors to South Sudan come to the country as part of a longer trip through Africa. Given South Sudan’s limited infrastructure, in particular its transport options, this isn’t a bad idea. Having your own vehicle gives you the ultimate freedom to travel where you want, and camping under the stars can really let you enjoy South Sudan at its most spectacular and wild. Detailed planning for a major overland trip is outside the scope of this guide, but there are several excellent resources out there to help you with your preparations. Bradt’s Africa Overland by Siân Pritchard-Jones and Bob Gibbons has comprehensive information on vehicle preparation, route planning and dealing with bureaucracy, and is a handy gazetteer for the entire continent.

Hitchhiking

In a country where public transport between villages is at best patchy, locals use hitching to get around all the time. Most commonly this means flagging down a big slow truck or a NGO’s 4×4 – there isn’t usually room in the cab, so you have to climb on top of the load and hang on tight. Free lifts are rare, however, and drivers will expect you to pay for the ride. There is almost an unwritten right to jump in a vehicle if there is space. South Sudanese can become offended if there is space and they are not availed a ride, a mistake many of the humanitarian and UN agencies make at the cost of much local trust and respect.

By boat

The Nile has long been Africa’s greatest transport artery, although travellers are unlikely to make great use of it unless purely for pleasure purposes. Compared with Egypt, the Nile in Sudan and South Sudan can often seem an empty river. There are currently no long-distance passenger ferries, and only cargo barges trawl the stretch from Juba to Malakal and, occasionally, north into Sudan.

When to visit South Sudan

If you wish to travel around South Sudan you will need to visit in the dry season, which starts at the end of November and lasts until late April. The wet season is slightly shorter in the north, due to its location further from the equator. Outside this period, roads (where are there are some) are frequently impassable, planes are often grounded due to poor visibility, and many villages are under a foot or more of water due to lack of drainage. If you are travelling to South Sudan to see the wildlife migrations, plan your trip for between March and April when the animals are moving from the floodplains of the Sudd south to the Boma National Park, or between November and early January when the same migration happens in reverse. The white-eared kob are calving in December and January, and seeing the calves could well be a highlight of your trip.

Climate

South Sudan’s climate is tropical, with high humidity and significant rainfall. Though there is regional variation due to altitude and terrain, the rainy season affects all parts of the country and occurs from April through until late October or early November. The rainfall is heaviest in the uplands, but diminishes in the flat plains of the north. The average daily temperature varies from 23°F to 37°C depending on the month, with March being the warmest month and July the coolest. Owing to South Sudan’s proximity to the equator, the hours of daylight remain almost constant throughout the year: the sun rises around 06.00 and sets again at 18.00.

What to see and do in South Sudan

Boma National Park

Boma National Park in northern Jonglei is one of the largest reserves in all of Africa: at 22,800km2 it is larger even than the many times more famous Kruger and Ruaha parks. The scale of the seasonal wildlife migrations is said to rival even that of the Serengeti, with as many as two million animals simultaneously on the move and with as many as 1.3 million of these antelope.

From March until June, the animals are moving south and east, from the floodplains of the Sudd and Bandingilo National Park across to Boma and into Ethiopia, keeping ahead of the rains. In the dry season months from November to January, the direction of the migrations is reversed. The animals return in search of pastures watered and made rich by the silt left behind by the flooding of the White Nile.

Bor

Bor’s tragic claim to fame is that it was the birthplace of the Second Civil War, when Sudanese army officer Kerubino Kuanyin led a revolt here in 1983. Built right on the eastern bank of the White Nile, it is the largest city in Jonglei, an historic centre for Christian missionary activity, and also the state’s capital. Bor is the best place in South Sudan to see the highly energetic Bor wrestling, as there are competitions here every weekend, and frequently you’ll have the opportunity to join in as well as spectate. If fighting isn’t your thing, you can also hire small canoes to paddle across the river to one of the many bustling Dinka cattle camps on the other side.

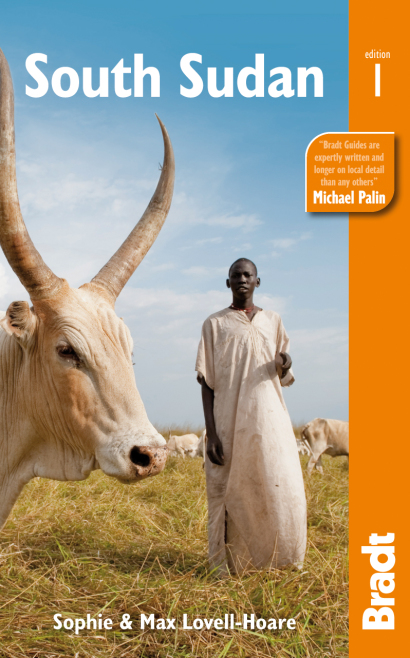

Dinka cattle camps

The Dinka are the most populous of South Sudan’s tribes and also the most politically influential. The majority of Dinka are still nomadic pastoralists and their cattle camps, which often contain 500 head or more of cattle, offer a fascinating insight into their traditional way of life. Much of South Sudan’s culture and history is derived from the importance of cattle: they’re the principal source of wealth and prestige, and, when pastures are scarce, the reason for so much conflict.

The Dinka are one of the most prominent cattle herding tribes and a visit to one of their cattle camps, where young boys and cattle live side by side, is to see into the heart of their community and learn about the central role these animals play.

Dr John Garang’s grave

The grave of John Garang is the closest thing Juba has to a pilgrimage site. It has no specific opening times and is heavily guarded around the clock, although if you approach the soldiers in a friendly manner they’ll permit you to go inside and probably even pose for photos. The grave itself measures 4m by 2m and appears to be covered in cream kitchen tiles, and there are bunches of faded plastic flowers for decoration. It is set within a surprisingly clean grassed area, although it’s not really a place you’d want to linger. Opposite the grave site is the John Garang Statue, erected in 2011.

(Photo: Rock formations at Jebel Barkal © Sophie Ibbotson and Max Lovell-Hoare)

Jebel Barkal

The holy mountain of Jebel Barkal (Jebel Barkal actually means ‘holy mountain’ in Arabic), a great sandstone butte that dominates this stretch of the Nile, is situated 2km southwest of the centre of Karima (a 15-minute walk or SDG5 in a rickshaw). The ancient Egyptians and Kushites alike believed that the mountain was the home of the god Amun, the ‘Throne of Two Lands’ – Egypt and Nubia. The ruins of a temple dedicated to the god lie at the foot of the mountain. At dawn or dusk, Jebel Barkal still evokes a phenomenal aura and it’s easy to understand why the ancients ascribed such religious significance to it.

Thutmose III, one of the first Egyptian kings to penetrate this far south, built the first Temple of Amun in the 15th century BC. Later pharaohs, including Rameses II, expanded it, turning it into an important cultural centre, as well as a way station for goods from the south destined for the great Temple of Amun at Karnak. When Egyptian influence waned the temple fell into disrepair.

The rise of the Kushites changed the fortunes of the whole region. Jebel Barkal became the centre of the new kingdom and its kings resurrected the worship of Amun. In around 720BC Piye led his armies north into Egypt and captured Thebes. Ownership of the Temple of Amun gave legitimacy to his claim to be the true representative of Egyptian traditions; his successors set up the 25th Dynasty and ruled from Thebes and Memphis as pharaohs. Piye greatly expanded the temple at Jebel Barkal, as did his son, Taharqa. Over time the temple grew to over 150m in length, making it the largest Kushite building ever built.

The temple stretches out towards the Nile, near the bottom of a freestanding pinnacle of rock cracked from the sandstone cliffs. The significance of this pinnacle has puzzled archaeologists for decades. An early observer supposed that it was to have been a giant statue of a pharaoh, far surpassing anything in Egypt at 90m high. A more likely explanation is found in its profile, which (albeit roughly) resembles an ureaus – the protective cobra and symbol of the king. A relief in Rameses II’s massive temple at Abu Simbel in Egypt shows Amun sitting inside a mountain, faced with a rearing cobra. This iconography is found in later Kushite art and almost certainly represents Jebel Barkal. In the 1990s, archaeologists discovered a niche at the summit of the pinnacle carved with hieroglyphics proclaiming Taharqa’s military campaigns against his enemies. This was completely inaccessible (except to the gods) so would have been covered with a gold panel, allowing it to reflect in the light and provide a beacon for miles around. The light of Jebel Barkal would have been clearly visible from Taharqa’s pyramid upstream at Nuri.

The temple is very ruined and much of the structure is covered with sand, but the ground plan is still clear, with a procession of two large colonnaded halls leading into the sanctuary at the base of the mountain, surrounded by several small rooms. At the southern entrance of the temple there are several wind-worn granite statues of rams; these were actually from Soleb further downstream and have been relocated here. There are many scattered blocks covered with reliefs and hieroglyphics.

Juba

Juba is an international city. In just a decade it has grown from a shell-damaged garrison town to a buzzing capital and is one of the 20 most expensive cities on earth. Unsealed roads swarm with ‘Daz white’ Land Cruisers, and the skyline and face of the streets is changing as shanty towns and refugee camps are being cleared to make way for brand new office blocks and hotels. Everything is in a state of flux. The fast pace of such changes is putting unprecedented pressure on Juba’s limited infrastructure and although foreign investment and expertise is coming, it will still be several years before road building, sanitation and power supplies reach the requisite levels. In the meantime, even Juba’s wealthiest expat inhabitants are in the unenviable position of paying US$150 or more for a night in a (albeit upmarket) tent, running their laptops off diesel-powered generators, and spending hours each day in traffic, their vehicles up to their axles in mud, especially during the rainy season (April–October).

It is a land of opportunity, no doubt, but one that requires a great deal of stoicism on the part of the workforce. The mix of foreign embassy and NGO staff, engineers and businessmen has given the city a cosmopolitan feel. In any bar or restaurant you can engage in lively debate about anything from the rights and wrongs of foreign aid, to the Chinese takeover of Africa, and you’ll never be short of places to eat and drink, providing, of course, that you can afford it. Traditional tourist sites in the city are few and far between, but you do not come to Juba to see ancient buildings or museums. Instead, you come to work, to make money or to make a difference (and occasionally both at once). Visit Juba to see a city and a country in a period of rapid transition, being catapulted into the 21st century but without a clearly-defined vision or plan as to exactly what that means. Whether you intend to participate or to observe, it is a fascinating place to be.

Kodok

The capital of Shilluk County and, for more than 16 centuries, the independent Shilluk Kingdom, Kodok is more famously known as Fashoda and was the setting for the Fashoda Incident. According to Shilluk tradition, it is the place where the spirits of Juok (God), Nyikango (the founder of the Shilluk kingdom and their spiritual leader), deceased kings and the living king come to meditate and dispense spiritual healing. Kings and community elders come here to hear the sounds and speeches of Juok and to reflect upon them. It is a holy place and, for more than 500 years, was closed to the outside world so that ordinary people would not disturb its sacredness.

The city came to international prominence in 1898 when French and British colonial powers almost came to blows over control of the territory, and though conflict was on this occasion averted, the term ‘Fashoda syndrome’ entered into French foreign policy.

Mount Kinyeti

East of Nimule lies the Imatong Mountains, which demarcate much of the border between South Sudan and Uganda. The massif rises steeply from the surrounding plains, reaching a pinnacle of 3,187m at the top of Mount Kinyeti, South Sudan’s tallest peak. The British explorer Sir Samuel Baker was the first foreigner to observe the Imatong when he visited the area immediately to the north and west in 1861, and 18 years later Emin Pasha, then governor of Equatoria, trekked along the eastern foothills. The mountains were not properly mapped until the 1920s when the topography was finally surveyed and recorded by the Sudan Government Survey Department.

The first botanical report, produced by Thomas Ford Chipp, deputy director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, was published in 1929 after he undertook fieldwork across the range and also made the first known ascent of Mount Kinyeti. The villages of the Imatong are inhabited by various Nilotic tribes, including the Acholi, Lango and Lotuko peoples. Having been ravaged during the Second Civil War and terrorised by the Lord’s Resistance Army who were, for a period, based in mountain hideouts here, the population is slowly recovering and returning to subsistence farming, though gun-related violence remains worryingly high.

Nimule National Park

Nimule National Park was established under British rule in 1954, and the park extends 540km2 along the border with Uganda, with wildlife moving freely back and forth, and straddles the White Nile River. It is probably the most easily accessible of South Sudan’s national parks, due to the proximity of public transport and also the fact that, unlike Boma, it can be reached even during the rainy season.

Try to arrive at the park offices (on the right as you enter the park) when they open at 08.00 to get ahead of groups coming down from Juba, and also to maximise the time you have out and about before the day gets hot. At the offices you need to buy your park permit, which can also be prepaid at the Ministry of Tourism in Juba and also collect your ranger: having a guide is compulsory so that you do not get lost and stray into landmined areas.

The ranger will take you down to the river where you can hire a local boat (SSP200) to take you across to Opekoloe Island. This is the best place to spot Nimule’s elephant herds, as well as hippos, crocodiles and the abundant river birdlife. Disembarking from the boat and continuing on foot, the ranger, adept at spotting tracks and creatures slinking silently and largely camouflaged through the undergrowth, should also be able to point out zebra, bushbuck, warthogs, baboons and Ugandan kob, as well as the occasional jackal, hyrax, vervet monkey or leopard. If you have time, ask your ranger to take you to the Fola Falls, an impressive, narrow passageway through which the White Nile flows. Daring fishermen cast their nets for catfish and other tasty treats, bravely running the gauntlet of crocodiles and hippos as they do so.

White-water rafting trips are the latest tourist addition in South Sudan, and rafting the White Nile in the Nimule National Park is an understandably popular weekend excursion for Juba expats. African Rivers run regular trips during the dry season, collecting rafters on Friday at lunchtime from Juba and driving them down to Nimule in a customised truck. Rafters camp in the park that night, and then start out early the following morning with three sets of Grade 4+ rapids in quick succession (this is not a trip for the faint-hearted and you must be able to swim).

It’s an exhilarating start to the journey, and whilst the later rapids are less challenging, the adrenaline remains high, in no small part due to the fact that crocodiles and hippos shadow the raft like hungry sentries for much of the time. Expect to finish each day soaked to the skin and utterly exhausted, but also falling in love with the wilderness and beauty of the place, and wondering how incredible South Sudan could be as a tourist destination one day if only politicians and wannabe politicians, both domestically and in neighbouring states, would leave well alone.

The Sudd

Shrek would be in his element in South Sudan, for among the numerous wetlands surrounding the White Nile and its tributaries is the world’s biggest swamp. It’s a veritable paradise for wildlife, although whether green, cartoon ogres are among them is anyone’s guess.

Also known as the Bahr al Jabal (mysteriously meaning ‘Sea of the Mountain’ in Arabic), the Sudd stretches across an area approximately 30,000km2 which increases dramatically in the wet season to more than 130,000km2. The water level in Lake Victoria, which straddles Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania and is Africa’s largest lake, is largely responsible for dictating the water level downstream as rainfall in this region is in fact slightly lower than in neighbouring areas on the same latitude.

Owing to the vast surface area of the Sudd, however, as much as half of the river water fl owing into the swamp evaporates long before entering the northward flowing Nile. The water meanders through innumerable channels and streams, winding its way into stagnant lagoons, fields of papyrus and marshy reed beds. The Sudd supports what is probably the highest level of biodiversity anywhere in South Sudan. The five core ecosystems – lakes and rivers, floating plant matter, river-flooded grassland, rain-fed grassland and peripheral woodland – support more than 400 species of bird, the world’s largest population of kob antelope, and significant numbers of other large game.

Patient tourists with a keen eye can hope to see hippopotamuses, crocodiles and the Nile lechwe waterbuck, and there are even reported sightings (though rare) of Lycaon pictus, the painted hunting dog. Birdlife is also diverse here and for bird-spotting possibilities. The Sudd is also rich in indigenous flora and much of the swamp is made up of naturally floating rafts of vegetable matter that can measure as much as 30km.

Wau

Wau is the main city of Bahr el Ghazal and South Sudan’s largest city after Juba, with a population a little over 150,000 people (2011 estimate). It sits on the western banks of the Jur River and, due to the prevalence of colonial-era buildings, including the unexpectedly impressive cathedral, the urban landscape and resulting atmosphere feels somewhat different from other cities in the country.

Wau has a pleasant climate, with a maximum temperature of 38˚C, and a rainy season that lasts from May to October. It is driest at the start of the year. There is no one dominant ethnic group in the city, and this, combined with the large number of UN agencies and national and international NGOs with offices and personnel in Wau, gives it an almost cosmopolitan feel. The aid presence has also ensured that there are a handful of decent places to stay.

White Nile

The Nile is one of the world’s mightiest rivers, and it is the lifeblood of South Sudan. A wide and impressive watercourse in the south of the country, on which it is possible to raft and see crocodiles and hippos lazing around, it peters out into the world’s largest swamp, losing much of its water to evaporation. In spite of this, it remains a haven for diverse wildlife and some of the best angling in East Africa.

White-water rafting on the Nile is a new addition to South Sudan’s tourist options, and you can enjoy a short splash at Nimule or paddle all the way to Juba. The rapids will make you buzz with adrenaline, especially when you realise just how many hippopotamuses and crocodiles are sharing the water, and in calmer stretches there are great possibilities for birdwatching and fishing.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to South Sudan: