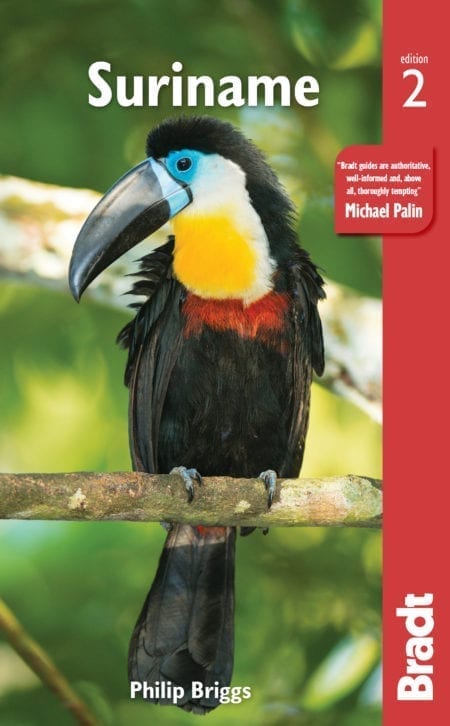

This vast and thinly inhabited wilderness is home to an untold wealth of wildlife, ranging from secretive, solitary jaguars to outsized psychedelic macaws that screech overhead.

Philip Briggs author of Suriname: The Bradt Guide

The most exciting emergent eco-destination in the Americas, Suriname has much to offer wildlife enthusiasts, adventurous travellers, and those who simply delight in quirky, non-mainstream destinations.

A true one-off, Suriname ranks among the world’s most thinly populated countries, and it supports a higher proportion of forest cover than any other place on earth.

Geographically, it is part of South America, politically it looks mainly towards the Caribbean, linguistically and historically it is inexorably tied to the Netherlands, its former coloniser. And culturally, it is none, or all, of the above, thanks to an ethnically diverse population of mixed West African, Indonesian, Asian, European and Amerindian descent.

Suriname’s most thrilling attraction is the unspoilt jungle that swathes 90% of its area. Home to playful monkeys, psychedelic macaws and crepuscular oddities such as tapirs and sloths, this vast tract of tropical greenery is best explored by taking a motorised dugout up one the rivers that form wide aquatic highways deep into the interior.

Here, a small number of astonishingly remote villages are inhabited either by Amerindians whose tenancy stretches back to the pre-Columbian era, or else by descendants of escaped slaves who still retain a strong West African cultural identity.

On the coastal belt, the capital Paramaribo is a lively and culinarily rewarding multiethnic city whose historic old quarter, lined with Dutch-Creole architectural gems, has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The nearby coast incorporates some of the world’s finest turtle-viewing sites, as well as superb aquatic and marine birdwatching, and several worthwhile forest reserves.

Despite all this, however, tourism to this safe and friendly country is still in its infancy, making it a fabulously rewarding travel destination for those who relish the truly wild and offbeat.

For more information, check out our guide to Suriname:

Food and drink in Suriname

Paramaribo, like most capital cities, has a varied and cosmopolitan culinary scene, with enough restaurants in most price brackets to keep you busy for weeks. Elsewhere, local eateries predominate, serving a range of Surinamese dishes reflecting the country’s diverse cultural heritage typically for around SRD 10–15 per plate. Most common is the ubiquitous Javan-style warung or eethuis (literally eat house), but these are supplemented in some towns by Chinese restaurants (which usually serve a mix of Javan-Surinamese staples and bona fide Chinese food) and Hindustani roti shops.

Vegetarians and more so vegans are quite poorly catered for outside Paramaribo (indeed, even within the capital, many prominent restaurants have a rather limited selection of vegetarian dishes by contemporary Western standards). Vegetarians and other travellers with specific dietary requirements will need to communicate these very clearly to the operator before they join any organised tour.

You’ll most likely drink a lot more in Suriname than at home, thanks to the hot sticky climate. It’s fi ne to drink tap water in Paramaribo and its environs, but probably not in more remote areas. Bottled mineral water is available in 1.5-litre and 500ml bottles in most supermarkets and shops, but independent travellers might need to stock up before heading out to very remote areas such as the Upper Suriname, Blanche Marie or Raleigh Falls (most organised tours include all the bottled water clients are likely to need). The usual brand-name soft drinks are also widely available, and most supermarkets will sell a range of fruit juice in cans and cartons. The most widespread alcoholic drink is Parbo Bier, an affordable and tasty locally brewed lager (made partly with rice) sold in one litre ‘djogo’ bottles and 500ml cans in most supermarkets, restaurants and hotels. Heineken is also produced locally, along with Chiller, which comprises lager beer favoured with passion fruit or lime, and is generally perceived to be a woman’s drink.

Health and safety in Suriname

Health

Suriname, like most tropical countries, is home to several diseases unfamiliar to people living in more temperate and sanitary climates. However, with adequate preparation, the chances of serious mishap are small. To put this in perspective, your greatest concern should not be the combined exotica of venomous snakes, stampeding wildlife, gun-happy soldiers or killer viruses, but something altogether more mundane: a road accident.

Within Suriname, a range of adequate (but well short of world-class) clinics, hospitals and pharmacies can be found in and around Paramaribo. Facilities are far more limited and basic in the interior. Wherever you go, however, doctors and pharmacists will generally speak fluent Dutch and some English, and consultation and laboratory fees are relatively inexpensive – so if in doubt, seek medical help.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety

Suriname is generally a very safe country for travel, judged by almost any standards. Indeed, the biggest concerns for most travellers should probably be insect-borne diseases such as dengue fever and road accidents, particularly for cyclists. It should also be pointed out that, as is the case almost anywhere in the world, breaking the law – in particular by using or handling illegal drugs – could land you in trouble.

Female travellers

Suriname is probably as safe as anywhere for women travellers. That being said, women travelling alone are frequently subjected to high levels of hassle in the form of staring, whistling, flirtatious behaviour and lewd propositions. Paramaribo is particularly bad for this sort of thing, though it might happen anywhere. Generally, make it clear that you are not interested, firmly but without being openly unfriendly, and you’ll soon be left alone. If hassle is persistent, it may sometimes help to pretend you have a husband at home or waiting for you (in which case wearing a wedding ring is accepted as ‘proof ’). It would also be prudent to dress more conservatively than you might at home, not so much to avoid offending local sensibilities but because it will help deter unwanted male attention. And while this attention can become cumulatively annoying, and some women travellers find it disrespectful or upsetting or both, we have heard nothing to suggest it might tip over into genuinely threatening behaviour.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Homosexuality, though legal, has a much lower profile than in most European countries. Nevertheless, while Suriname is probably not suited to anyone seeking an active gay scene, gay couples are unlikely to encounter any problems with discrimination in hotels and other tourist institutions. The homosexual age of consent is 18, two years higher than the heterosexual age, but this is seldom enforced. The law does not recognise homosexual marriages, civil unions or domestic partnerships, nor does it actively protect gays and lesbians from discrimination. Since 2011, the country’s most prominent gay and lesbian organisation LGBT Platform Suriname has held an annual Gay Pride march called OUT@SU every 11 October to coincide with International Coming Out Day.

Travellers with a disability

Suriname, in particular the deep interior, is not generally well suited travellers with mobility problems. Transport and accommodation away from the few main roads tends to be basic, often involving boat rides that would be risky to anybody who cannot swim. Travellers with disabilities wanting to visit Suriname should liaise closely with an upmarket local operator who is aware of the exact nature of their disabilities and what limits these might impose on them.

Travel and visas in Suriname

Visas

All visitors must produce a passport on arrival. Check well in advance that your passport hasn’t expired and will not do so within six months of your date of arrival, or you risk being refused entry to the country. Most visitors require either a visa or a tourist card, the only exceptions being nationals of Argentina, Aruba, Bonaire, Brazil, Curaçao, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Saba, St Eustacius, St Maarten, South Korea and Singapore, who may enter the country freely (in some cases for up to 30 days only without a visa). Be aware that visa requirements frequently change, so it’s advisable to check for up-to-date information before you travel and the best source of clear and detailed current information (in English or Dutch) is the website of the Suriname Consulate in the Netherlands.

Getting there and away

By air

Most visitors to Suriname fly from Europe, the USA or the Caribbean. However, only four international carriers fly to Paramaribo, as detailed below, and while there are direct flights from Miami and Amsterdam, there are none from elsewhere in Europe. Flights from the UK tend to be quite costly, with Caribbean Airlines usually the cheapest option.

All international flights land at Johan Adolf Pengel International Airport (JAPI) about 45km south of Paramaribo. Usually referred to as Zanderij Airport, JAPI is serviced by a few unremarkable cafés and shops, most of which only kick into action to coincide with incoming or outgoing flights, and a branch of the DSB Bank which has a 24-hour ATM where local currency can be drawn against a Master or Maestro card. There is also a Digicell shop (where you can buy a local SIM card), and kiosks for the main car rental companies: Avis, Budget and Ross.

Most people arriving at JAPI book a shuttle transfer to the city through their hotel. This typically costs around SRD 35–50 per person in an air-conditioned bus, including drinking water, and takes up to two hours depending on traffic. If you don’t have a transfer booked, several kiosks in the airport lobby represent various shuttle companies.

By vehicular ferry

You can cross into Suriname from neighbouring Guyana and French Guiana (the latter actually a département of France and thus part of the European Union). In both cases, the border crossing is by boat or motor ferry. Both crossings are quite straightforward in terms of bureaucracy as long as your papers are in order. EU passport holders do not need a visa to cross into French Guiana. Visas for Guyana, if required, can be bought at the consulate in Nieuw Nickerie.

Getting around

Paramaribo is the point of departure for all domestic flights, as well as being the hub for the country’s road network and most associated public transport. This road network is very limited, consisting as it does of around 4,000km of surfaced and unsurfaced roads. These include the surfaced east–west link running along the coastal belt east and west of Paramaribo to Albina (on the border with French Guiana) and Nieuw Nickerie (on the border with Guyana), a small grid of mostly surfaced roads through the plantations of Commewijne District, a network of surfaced roads running south from Paramaribo through Wanica and Para to Zanderij (site of Johan Adolf Pengel International Airport), a surfaced road running north from Zanderij to Brokopondo and the small port of Atjoni on the Upper Suriname, and a long rough dirt road running west through the interior from Zanderij to Apoera. Most other parts of the country are accessible only by boat or by light aircraft, or are effectively inaccessible to tourists.

Self-drive

This is an excellent way for flexible and confident travellers to explore the coastal districts and the vicinity of the Suriname River as far south as Brokopondo. Cars or 4x4s can be rented affordably through a few companies in Paramaribo and most sites of interest are within easy driving distance on well-maintained surfaced or dirt roads.

By bus

Most roads in Suriname are covered by some form of public transport. This includes the cheap, extensive and reliable bus network operated by the parastatal National Transport Company.

By boat

Boat transport is a big part of travel in Suriname. Affordable waterborne public transport connects Paramaribo to several sites on the east bank of Commewijne, as well as servicing the Upper Suriname and Gran Rio from Atjoni south to Kajana, the Corantijn River from Nieuw Nickerie south to Apoera, and the Cottica River near Moengo. Ferries or taxi-boats are also the only way to cross between Suriname and its Guianan neighbours (Guiana and Guyana). Several other sites visited by organised tours are also most easily accessed by boat, ranging from the remote Raleigh Falls to the north bank plantations of Commewijne, the turtle-nesting beaches at Matapica and Galibi, and birding sites such as Bigi Pan.

When to visit Suriname

Suriname can be visited at any time of year. Being close to the Equator, temperatures are not strongly seasonal, with daily averages in Paramaribo ranging from 27–29°C throughout the year. The low-key nature of tourism means that seasonal overcrowding is not really a concern either. In most respects, however, the best time to visit Suriname is during the relatively dry months of February to March and August to November, and the worst time is during the wettest months of May to August, when the interior in particular is prone to flooding and the already limited road network becomes even more so. For wildlife enthusiasts, turtle viewing, a very popular activity, is best from late February until May, although leatherbacks keep laying until August. Migrant shorebirds are most prolific from mid-August to late April.

Climate

Its equatorial location and low altitudes ensure that Suriname has a typically hot, sunny and moist tropical climate. Temperatures are fairly consistent throughout the year and countrywide, typically hitting a daily maximum of around 30°C, exacerbated by a high relative humidity (typically more than 80%) but tempered in many areas by a river or sea breeze. Average annual rainfall in most parts of the country is around 2,000mm. It rains year-round, mostly in the form of short dramatic cloudbursts, but rainfall peaks during the two wet seasons, which run from late April to August and from November to February. There is still quite a bit of rain in the intervening dry seasons, as indicated in the weather charts below, with Paramaribo being typical of the coastal belt and Brokopondo of sites further inland.

What to see and do in Suriname

Bergendal Eco-Resort

One of the most popular destinations for overnight trips from Paramaribo, Bergendal Eco-Resort opened in 2008 on a 24km2 patch of forest that was formerly part of the Bergendal Plantation. Set on the west bank of the Suriname River, the resort provides a an excellent ‘soft’ introduction to the Surinamese interior, combining a genuinely wild setting and jungle feel with exceptionally comfortable upmarket accommodation and facilities. It is also easy to access along a good asphalt road that runs from Paramaribo to within 2km of the entrance gate. Bergendal is popular with outdoor lovers of a more active disposition, as a topnotch adventure centre that runs daily zipline cableway trips through the forest canopy, as well as day walks, kayaking and motorised boat trips can be found nearby. And while upmarket tourism is focused on the eco-resort, there is also more affordable accommodation on offer at the adventure centre. Not much further afield, agreeable budget accommodation, safe swimming and wonderful birding are available at the excellent New Babunhol River Resort, only 8km north of Bergendal. Those on a tighter budget can sling up a hammock at the low-key Bena Resort in the riverside transmigration village of Klaaskreek.

Brownsberg Nature Park

About 100km inland from Paramaribo as the crow flies, and readily accessible by road, the scenic and wildlife-rich Brownsberg Nature Park is one of the most popular destinations for organised day trips from the capital. Created in 1969, the 112km2 park protects the forested slopes of Brownsberg (‘Brown’s Mountain’), which rises to an altitude of 560m immediately east of the Brokopondo Reservoir. Around 1,500 types of plant have been recorded in the park, as have 410 bird species. It is also one of the most reliable sites in Suriname for seeing large mammals, with red howler and black spider monkey both common in the vicinity of the camp, along with several smaller monkey species and the twitchy little agouti. The mountain, like nearby Brownsweg, is named after John Brown, who worked the slopes in the late 19th century (some of his diggings can be seen along the footpaths close to camp). Ironically, illegal gold mining is today probably the biggest threat to the park’s wildlife. In 2012, the WWF discovered 50 illegal gold-mining sites in the vicinity of the park, which aside from contributing to local deforestation, can result in increased subsistence hunting for bush meat and also mercury contamination of the soil and water. The park receives an estimated 18,000 visitors annually, a high proportion of which are local weekenders from Paramaribo, so it tends to be quietest on weekdays.

Central Suriname Nature Reserve

Suriname’s most important conservation area, the CSNR accounts for almost 10% of the country’s surface, extending over 16,000km2 of untrammelled lowland and montane forest. It was created in 1998 following the amalgamation of three smaller nature reserves designated in the 1960s (namely the 780km2 Raleigh Falls, 2,200km2 Eilerts de Haan Mountains and 1,400km2 Tafelberg Nature Reserve) with the vast corridor of forest that links them. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1990, the CSNR is not only the largest reserve in Suriname but also the fi ft h-largest terrestrial protected area anywhere in South America. Th e CSNR incorporates Suriname’s tallest mountain, the 1,280m Juliana Top in the Wilhelmina Range, along with the 1,026m Tafelberg (‘Table Mountain’) and many smaller granite domes of which the best known and most accessible is the 245m Voltzberg. It is bisected by the Coppename River, which forms part of the western boundary and is also the usual access point for tourists. It also incorporates important headwaters of the Suriname, Saramacca, Kabalebo and Corantijn rivers. Th e reserve is an important stronghold for large mammals such as jaguar, puma, ocelot, tapir, giant river otter, and it harbours all eight primate species recorded in Suriname.

The Commewijne Plantation Loop covers a 60km road that runs past several of the more popular sites © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

The Commewijne Plantation Loop covers a 60km road that runs past several of the more popular sites © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Commewijne Plantation Loop

This section covers a 60km road loop that runs past several of the more popular and worthwhile sites in Commewijne District, notably Peperpot Nature Park and Fort Nieuw Amsterdam. Although the sites included here are thematically diverse, and any one of them could be visited without the others, it seems practical to group them together for logistical reasons. The main transport hub along the plantation loop is Meerzorg, a small town on the east bank of the Suriname River directly opposite Paramaribo, and linked to it by the Wijdenbosch Bridge and regular taxiboats. From Wijdenbosch Bridge, the road loop runs west for about 4km through Meerzorg to a major intersection close to the entrance of Peperpot, then north for 15km to the district capital Nieuw Amsterdam, site of the eponymous fort. From here, it follows the Commewijne River east for around 15km to Alkmaar, offering access to the Mariënburg and Katwijk plantations (as well as a jetty from where you can cross to the north bank), then runs south to rejoin the main road between Meerzorg and Albina at Tamanredjo Junction.

Jodensavanne

Arguably the most important and intriguing historical site in Suriname, the ruins of Jodensavanne (‘Jewish Savannah’) stand on the elevated east bank of the Suriname River some 50km upstream of Paramaribo. Now largely engulfed by jungle, this ruined town was Suriname’s second-most important settlement from the late 17th century until its demise in the early 19th, and it is also a remote and poignant reminder of the South American exodus undertaken by some of the 800,000 Sephardic Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula by the Spanish Inquisition in the 1490s. Its most significant building is the ruin of the oldest brick synagogue constructed in the Americas, but the site also houses an extensive cemetery comprising 452 known graves marked with (mostly engraved) stones. The neglected and largely unexcavated site was placed on the World Monument Fund Watch List in 1996, and the Stichting Jodensavanne, Jodensavanne Foundation (JSF) has since helped to publicise its existence and to enhance visits with the provision of good onsite interpretative material. Jodensavanne was designated a national monument in 2009 and it is the only place in Suriname currently included on UNESCO’s tentative list of proposed World Heritage Sites.

Kabalebo Nature Reserve

The closest thing in the Surinamese interior to a genuinely world-class eco-lodge, the private Kabalebo Nature Reserve also provides some of the region’s finest wildlife viewing and birding, thanks to its isolated location in a region with no permanent villages. The reserve was established in 2004 when the dynamic owner-managers built Main Lodge next to Kabalebo airstrip (cut in 1962 and a relic of Operation Grasshopper), around 150km from the closest road. Today, the reserve supports three different lodges overlooking the Kabalebo River (a tributary of the Corantijn) and the forested Misty Mountain, which rises to around 250m on the opposite bank. As with many other sites in the interior, the reserve supports a varied birdlife (around 300 species have been recorded) along with conspicuous populations of several monkey species, but it is also perhaps the best place to seek out more elusive medium to large mammals. The lowland tapir is often seen crossing the airstrip, the peculiar capybara and giant river otter are frequently encountered on boat trips, the beautiful ocelot often visits the camp at night and jaguars are observed in the vicinity from time to time. Activities on offer include guided walks, kayaking, swimming in the various rapids and waterfalls, game fishing, birdwatching and night walks. Facilities include a wide wooden balcony where you can relax on a hammock, a large swimming pool surrounded by a varnished wooden deck and shady sunbeds and a well-stocked honesty bar. Also impressive are the friendly English-speaking staff, the relatively high standard of guiding the and unusually varied buffet-style meals.

Kwamalasamutu

The most southerly destination in Suriname, Kwamalasamutu is a legendarily remote Amerindian village set on the banks of the Sipaliwini River, close to its confluence with the Corantijn. It is home to around 1,000 predominantly Tiriyó inhabitants, who were first exposed to the outside world in 1960 as a result of Operation Grasshopper, and have since been heavily influenced by the teachings of Baptist missionaries.

The main attraction of the region is the elaborate petroglyphs engraved into the walls of the Werehpai Caves, which lie about two hours’ walk from the village along a rough jungle path. Discovered by outsiders in 2004, Werehpai is a formation of gigantic boulders and overhangs that extends across a couple of hectares, and is decorated with at least 350 ancient rock carvings, the greatest concentration in the Amazon region. Depicting humanoid forms, animals and abstract patterns, the richly symbolic petroglyphs are almost impossible to date, but are probably more than 4,000 years old, the work of unknown forest dwellers presumably ancestral to the Amerindians that inhabit the region today. The rocks are also a nesting site for the Guianan cock-of-the-rock.

Matapica Beach is the ideal spot for turtle viewing © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Matapica Beach is the ideal spot for turtle viewing © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Matapica Beach

One of the region’s most important marine turtle-nesting sites, Matapica Beach is the name loosely applied to the 20km of wild uninhabited Atlantic coastline that stretches east from Braamspunt (on the combined estuary of the Suriname and Commewijne rivers) to the mouth of the smaller Matapica Creek. Unusually for Suriname, the coastline here is predominantly sandy, and while the water might be a little too rough and murky for it to qualify as a conventional beach resort, it does provide ideal conditions both for the turtles to lay their massive clutches of eggs, and also for visitors to witness this thrilling phenomenon. In terms of turtle encounters, we regard Matapica as the best site in Suriname, since you are based right on the beach, and thus have a better chance of daylight sightings than you would at better-known rival Galibi. The most common species here, as in Galibi, is green turtle, but leatherbacks are also quite frequent. Olive ridley and hawksbill turtles also nest here, but very occasionally and sightings are rare. The main nesting season for green turtles runs from February to May, and for leatherbacks from April to July. Turtles are highly unlikely to be seen at other times.

Be enchanted by the Dutch-Creole architecture of the Historic Inner City of Paramaribo © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Be enchanted by the Dutch-Creole architecture of the Historic Inner City of Paramaribo © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Paramaribo

Paramaribo is not only the capital of Suriname, it is also the country’s largest population centre and its main transport hub. Often referred to as Parbo, it’s a safe, welcoming and decidedly beguiling city, steeped in history and strong on character. Founded in the early 17th century on the west bank of the Suriname River, the inner city is renowned for its unique and thoroughly attractive Dutch-Creole wooden architecture, which earned it recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002. Yet despite this Dutch architectural heritage, Paramaribo today is a strikingly multi-ethnic city, one whose diverse population of 250,000 primarily reflects successive waves of forced and voluntary migration from Europe, West Africa, Indonesia, India and China, but also includes a small number of indigenous Amerindians. The Surinamese capital is also justifiably proud of its reputation for religious and ethnic tolerance, epitomised by its grandest mosque and oldest synagogue rubbing shoulders on Keizer Straat, a block west of a historic Dutch Reformed Church.

It is fortunate that Paramaribo is such a gem of a city, as anybody planning a trip to Suriname will quickly recognise that almost all the country’s roads converge on the capital, as does pretty much every last bus service, domestic flight and organised tour. As a result, visitors tend to end up planning around several one- and twonight stays in Paramaribo between upcountry excursions. This, it must be said, is no hardship. The UNESCO-endorsed inner city warrants a full day’s exploration, starting with historic Fort Zeelandia and its excellent national museum. Further afield, Paramaribo offers rich pickings for day trippers: a leisurely stroll through the forested Peperpot Nature Park to look for colourful parrots and toucans, a relaxed cycling excursion to historic Fort Nieuw Amsterdam and the old plantations of Commewijne, a boat trip in search of the dolphins and marine birds that frequent the mouth of the Suriname River, an all-day organised tour to beautiful Brownsberg Nature Park or a bus trip to Lelydorp’s underrated Neotropical Butterfly Park. And after the day’s adventures, it is a genuine pleasure to while away the balmy tropical evening over a few chilled drinks on the breezy riverside Waterkant, or to work through a few of the city’s countless eateries, which range from cheap and cheerful Javan-style warungs and Indian-style roti shops to a surprisingly cosmopolitan but still mostly affordable selection of smarter restaurants.

Take a boat up the river and pass the isolated villages of Upper Suriname © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Take a boat up the river and pass the isolated villages of Upper Suriname © Ariadne Van Zandbergen

Upper Suriname River

The most easily explored part of Suriname’s interior comprises the Upper Suriname River, which stretches inland from the southern shore of Brokopondo Reservoir to the northern base of the remote Eilerts de Haan Mountains. Wild and largely untrammelled despite its relative accessibility, the Upper Suriname is lined with a few dozen small settlements and 20-odd island-bound or riverside lodges, all of which share a down-to-earth rustic feel in keeping with their jungle surrounds. It is also one of the most exciting parts of Suriname to visit, whether you opt to splash out on a fly-in package to the relatively upmarket Anaula, Danpaati or Awarradam, or to explore the river more whimsically, staying at budget lodges and using inexpensive taxi-boats to propel you slowly southwards.

A compelling feature of the Upper Suriname is its rich traditional culture. The only inhabitants of the region are the Saamaka, or Saramacca, descendants of escaped slaves who made the river their home several hundred years ago. The ancient African roots of the Saamaka are manifested vividly not only in the physical appearance of the people, but also in their social structure, in the organic wood and palm frond constructions that typify their smoky villages and in a traditional culture steeped in animism and ancestor worship. Every so often whilst on the river, a small dugout paddles past manned by two or three people off to visit a neighbouring village or go fishing for their evening meal, a scene that could come straight out of West or Central Africa. Indeed, though the Upper Suriname is part of South America, there is an oddly African quality to it.

Large wildlife is scarcer (or perhaps just shyer) here than it is along Suriname’s less populated waterways, largely as a result of hunting. Still, it’s not unusual to see squirrel monkeys as you cruise upriver, or to hear the eerie communal calls of distanthowler monkeys. And birds are everywhere. Pairs of pied water-tyrant sit perkily on the rocks, often accompanied by cryptically camouflaged ladder-tailed nightjars and small flocks of white-banded swallow. Ringed and green kingfishers flash past a few metres above the water. The delicately marked striated heron is common, but you might also see the occasional (much larger) cocoi heron wading in the shallows, or a capped heron foraging below the rapids. Brightly marked parrots and toucans roost in riverside trees or flap noisily overhead, while raptors such as the dramatic swallow-tailed kite are mobbed by the ubiquitous greater kiskadee.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Suriname:

Related articles

Nothing found.