If the oil should ever run out, the twin rivers will still uncoil like giant pythons from their lairs in High Armenia across the northern plains, will still edge teasingly closer near Baghdad, still sway apart lower down, still combine finally at the site – who knows for sure that it was not? – of the Garden of Eden, and flow commingled through silent date-forests to the Gulf. Whatever happens, the rivers – the life-giving twin rivers for which Abraham, Nebuchadnezzar, Sennacherib, Alexander the Great, Trajan, Harun Al Rashid and a billion other dwellers in Mesopotamia must have raised thanks to their gods – will continue to give life to other generations.

Gavin Young, author of Iraq: Land of Two Rivers

Iraq, the land between the two rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, is a jigsaw puzzle with three main pieces: the mountainous snow-clad north and northeast making up about 20% of the country, the desert representing 59%, and the southern lowland alluvial plain making up the remainder.

The history of Iraq has often been a history of conflict and bloodshed, but during periods of serenity, splendid civilisations have emerged to make numerous indisputable contributions to the history of mankind: it is the land where writing began, where zero was introduced into mathematics, and where the tales of The Thousand and One Nights were first told. Iraq was the home of the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon and the mythical Tower of Babel. Al-Qurna is reputed to be the site of the biblical Garden of Eden. Splendid mosques and palaces were built by rulers who insisted on nothing but the most magnificent. Through trade, Iraq absorbed the best of what its neighbours had to offer and incorporated the innovations of others into its own unique civilisation.

In the 20th century Arab nationalism was nourished in Iraq – it was the first independent Middle Eastern state and developed a strong Arab identity. Art was encouraged and Baghdad became the venue for many international cultural festivals.

But the 20th century was also the time of the Iran–Iraq War, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the subsequent war. The Iraqi people also suffered from some of the most stringent economic sanctions ever imposed by the United Nations, and from Saddam Hussein’s totalitarian regime.

The dream of a better future after the 2003 war, when the US-led Coalition toppled Saddam, soon turned sour and there began years of sectarianism, insurgency and sheer misery for the ordinary Iraqi. Much of the budget originally allocated by the USA for a massive rebuilding programme was diverted into maintaining security.

However, with the departure of the US occupying forces in 2007 and the establishment of Iraqi rule and with good, free elections in 2014, the country was beginning to stand on its own two feet. Iraqis are a resilient people. The mistakes are theirs, the triumphs are theirs, the future is theirs.

But how could anyone have envisaged the advent of ISIS (Daesh) in June 2014 and the rapid and almost total collapse of the Iraqi forces and the invasion of Iraq, the taking of Mosul and Kirkuk, Barji and Tikrit, the advance on Baghdad and the taking control of the desert lands of Anbar Province by the so-called Islamic Caliphate based in Raqqa in Syria.

After many battles, ISIS were defeated by a combination of Iraqi and Coalition troops. Following this, and the months of political and civil unrest at the end of 2019, it will take time for the Baghdad government to recover, to replace its ministers for a fresh approach to combat its own sectarianism, which encouraged support for ISIS in some communities, notably in the north of Iraq. The chaos and fleeing of vast numbers of people, both inside and outside of its borders in response to the atrocities of ISIS, destruction of their homes and the fighting back of Kurdish forces and the Iraqi army against this invasion, was immense and exacerbated the divisions between the Kurdish regional government and the Iraqi government in Baghdad.

This is an opportune moment to update the current Bradt guide to Iraq. Mesopotamia – the land between the two rivers – continues to be the heritage of the world. Its civilisations, the ancient and historical sites, and the advances of knowledge that took place at these sites over thousands of years, have changed all our lives. Despite Covid, many of the restrictions in place over the previous few years are gradually starting to be lifted, meaning that visitors can again travel in many of the places described in this book and we look forward to the day, hopefully soon, when access to all areas of Iraq is possible. As we have said, the Iraqis are resilient people and with a little help from their friends, the country will recover.

For more information, check out our guide to Iraq

Food and drink in Iraq

Iraqi cuisine has been influenced by the ancient spice routes, when spices were brought to the Middle East from India and Persia more than 3,500 years ago. Poets lauded the creations of Abbasid chefs that included various goat meat dishes and spitted gazelles. Iraqi dishes are extremely varied, ranging from meat and chicken kebabs to quzi, traditionally a whole lamb stuffed with rice, almonds, raisins and spices.

The most famous Iraqi dish is mazgouf, redolent of the biblical Tigris fish: as night falls a glittering necklace of lights illuminates the water, fishermen return with their fresh catch to the open-air restaurants along the riverbank. Split and hung to smoke lightly over a charcoal fire, the fish is laid above the glowing ashes and filled with peppers, spices, onions and tomatoes. Every restaurant and family has its own secret recipe.

With Iraqi food you get a lot for your money. A large selection of salads and plentiful amounts of bread accompany every meal. Arab hospitality is inseparable from sharing a meal with friends, and to share food together is one of the best and most enjoyable ways for people of two cultures to cross boundaries and to establish a friendship.

Dining out

Before urbanisation, a cooked breakfast and dinner were the main meals as people worked in the fields and did not return home for lunch. Today, however, lunch is the main meal, eaten after 2pm when offices have shut for the day. Meat, lamb or chicken, in the form of kebabs, are nearly always served during the midday and evening meals. The price of a three-course meal in a local city restaurant will cost about US$15–20 per person; however, in one of the better hotels the price will probably be double that.

There are, of course, local variations. For example, the locally caught fresh fish is excellent in the mountain regions. Baghdad is famous for its mazgouf, a flat fish native to the Tigris. Half the pleasure is in watching it being prepared. It is split and roasted in the open air on stakes around a wood fire. Unfortunately, unless properly prepared, it has an overwhelming taste of mud! It is not an inexpensive meal either.

Virtually all the large hotels in Iraq, and many of the medium-sized ones, have restaurants of varying quality. The very best hotels in the major cities have excellent restaurants, with Iraqi food alongside international cuisine. In the cities and most big towns you will find a selection of foreign restaurants, usually Italian, as well as fast-food restaurants and take-aways serving wraps, burgers and pizza.

Local restaurants tend to be small and scattered all over the towns and suburbs. It can be difficult to find one with a varied menu, as despite their often elaborate (and badly translated) menus, you will usually find they serve little more than chicken, rice and kebabs, with maybe soup and a side dish of beans or aubergine. Local breads, which vary slightly from town to town, are excellent if freshly baked.

The bazaars are the perfect places to find authentic, local food. Seek recommendations from the locals, taxi drivers or hotel staff.

Drink

Tea is the national Arab hot drink and there are few problems that cannot be solved over a glass of tea. Turkish coffee, which is available in hotels, is also very good. It is advisable not to drink the tap water.

Alcohol is rarely served with meals although it may be available in the bar in certain very upmarket restaurants and hotels (mostly in the cities of Kurdistan such as Erbil, Duhok and Suleimaniyah), but you are highly unlikely to find it elsewhere and never in the Shrine Cities.

In Baghdad the liquor shops are open again after a short period of closure due to the violence directed against them. Most of these shops are located in the Karada district and along Sadoun Street. The sellers are either Yezidis or Christians. Under Saddam Hussein the rules were tightened up in an effort to prevent drinking in public, and these laws have not subsequently been rescinded.

Alcohol is not served in most restaurants or clubs. Do not attempt to bring liquor to any such places however well it is wrapped up or disguised. Alcohol is not served in most hotels and many also forbid alcohol being brought on to the premises. Whenever you purchase alcohol make sure it is well wrapped in a black plastic bag and transfer it to your own bag if possible. If you do take it to your hotel room, make sure you keep it out of sight and remove all empty bottles and packaging afterwards, discreetly discarding these in municipal bins away from the hotel premises.

Health and safety in Iraq

Health

Vaccinations

It is advisable to be up to date with all primary immunisations including tetanus, diphtheria and polio – an all-in-one vaccine (revaxis) lasts for ten years. Vaccinations against hepatitis A and typhoid are also recommended for visitors to Iraq.

Vaccinations for rabies are advised for everyone, but are especially important for travellers visiting more remote areas, especially if you will be more than 24 hours away from medical help and definitely if you will be working with animals.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available here. For other journey preparation information, UK travellers should consult Travel Health Pro in conjunction with advice given by your doctor prior to or during travel.

Safety

There are parts of Iraq in which it is currently not safe to travel and in all parts of Iraq caution should be exercised by foreigners at all times. At the time of writing, the FCO advises against all but essential travel to Iraqi Kurdistan and against all travel to everywhere else in the country. For up-to-date security information, go to the FCO website.

It is necessary for any foreigner travelling in Iraq to understand and be aware of the risks and dangers, which vary across the country and also depend upon whether you are residing in one place for a short time or travelling around. Each of these carries its own risks. Business visitors and academics will have to rely totally on their sponsoring hosts who will be responsible for providing them with their security, comprising armed personnel which accompany each group and carefully planned routes. All hotels with foreign guests will also have in-house security.

Tourist groups should always be accompanied by armed security (in civilian clothing) on provided transport. When visiting areas where there have been recent disturbances, the special police force protection squad will accompany the tourist vehicle. The somewhat complicated liaison procedures between the provinces and resulting time wasted while collecting escorts can be irritating, but at the end of the day it is for your benefit.

Each province has its own procedures and ideas of how and when to protect you. Each hotel, each site and each historical and religious building will have its own guards and security. Invariably the accompanying police squads will be cheerful and good company. The downside of all this is that sometimes the perception of danger takes over and you cannot get to where you hoped to go. Also the guards and security people take their duties so seriously that sometimes you can feel unable to move freely at all. However, it is a testament to the thoroughness of the various security organisations that tourist groups have not had any real trouble in the last decade.

The traveller/tourist/businessperson has to also play their part. Sensible, modest clothing, no expensive jewellery and most importantly good camera discipline. Do not take photographs when asked not to and be aware that at religious sites such as Kerbala and Najaf pilgrims, especially women, do not want large cameras in their faces at times of religious privacy. Your tour guide should inform you at such places what is and is not possible. Try to avoid drawing too much attention to yourself and walk sensibly through crowds. As you will be accompanied by security personnel, crime tends not to be a problem.

Female travellers

Foreign women are often considered ‘honorary men’ and given the opportunity to share the company of both men and women in a way foreign men cannot. The vast majority of female travellers to Iraq experience no adverse treatment because of their gender, as long as they dress and behave modestly and respect Islamic dress codes at Shia shrines and in the holy cities.

It is worth emphasising, though, that these are highly orthodox religious places and the dress code imposed here can be a shock to Western women, even those who consider themselves regular and experienced travellers to Muslim countries. Dressing modestly here is absolutely essential which means not one strand of hair showing and dark, voluminous clothing revealing nothing more than the face and hands.

Travellers with disabilities

Although many of the new shopping malls and some of the newer hotels, especially those being built with foreign investment, are starting to include access for travellers with a disability, generally speaking Iraq is not terribly well equipped for such. Many of the smaller hotels don’t even have European-style toilets or a lift, and you are unlikely to get any help with carrying your bags from the staff. That said, most of the pavements and roads in the major cities are in reasonable condition.

The major public transport option, taxis, are rarely able to carry wheelchairs, although as newer vehicles start appearing in the major cities this may change. The Shrine Cities are more able to cope with people with mobility problems, albeit not in ways we are used to in the West. Many pilgrims visit the Shrines seeking blessings and cures, and wheelbarrow-style ‘carts’ can be found in profusion transporting people around the shrines and their environs. If you have a disability and are considering a trip to Iraq, it is advised that you approach a tour operator, discuss your individual requirements and establish what provisions can be made.

LGBTQ+ travellers

Under Saddam Hussein, Iraq did not have a law against homosexuality and that remains the case today. However, as in most Middle Eastern societies, homosexuality is generally not approved of for religious and cultural reasons, leading to it being somewhat of an ‘open secret’; everyone knows it happens, but nobody talks about it.

If you are travelling in Iraq with a same-sex partner, you are advised to refrain from public displays of affection (although two men holding hands is seen as perfectly normal and acceptable) and to be circumspect when discussing your relationship with others.

Single rooms are quite an alien concept in hotels in Iraq; most rooms have two (or more) beds in them and so no-one raises an eyebrow at a request for same-sex sharing of rooms – in fact there is often no alternative! The situation is a little more relaxed in Kurdistan where an acceptance of the open practice of sexual freedom is beginning, albeit in a small way in the younger generation living in the major cities such as Erbil.

Travel and visas in Iraq

Visas

In common with most Arab countries, you will probably be refused a visa if your passport contains an Israeli stamp or any crossing point with Israel including the Araba border, Sheikh Hussein border, Rafah border and Taba border. For foreign nationals there are four main types of visa to Iraq:

- Business/academic visas

- Pilgrim visas

- Tourist visas

- Press and media visas

The usual validity for a visa is three months and the maximum stay is 30 days. You will need an invitation from the commercial company, university or tour operator who will be sponsoring you. Note that individual tourist visas are not issued owing to the security situation and the tour operator has to have a minimum of seven to ten persons before any tourist visa can be issued. If applying at an embassy you will need to complete the forms and supply photos, your passport and the fee (check for current cost at time of application, see opposite for embassy contact details), plus your sponsor’s invitation letter.

The alternative is to obtain the visa on arrival at the airport of your choice. This has to be arranged well in advance by your tour operator or sponsor. They will supply the documentation on your behalf and usually meet you at the airport to facilitate the process. Visa fees at the airport are currently US$52 for single entry; US$200 for multiple entry (usually for business purposes).

Do not attempt to travel anywhere in Iraq without your passport containing your Iraqi visa and stamp. There are an enormous number of roadblocks and checkpoints on every road in every town and city at which you and your passport will be examined.

Getting there and away

By air

Your entry point to Iraq is likely to be through one of the two international airports: Baghdad and Basra. At the time of going to press, numerous airlines served these (a selection of which are listed below). Unsurprisingly, routes and flights are subject to constant change, especially with Covid-19 restrictions, so visit individual operator’s websites for full details of the current services.

By land

Iran to Iraq

Northeast of Baghdad runs the route through Diyala Province to the main International Border Post of Khorasan and the Iranian border. It is approximately 90km and along the way there are some patches of good road.

Jordan to Iraq

The western border with Jordan is open between Karamal on the Jordanian side and Tarabil on the Iraqi side. This border is a very important one for Iraq and consequently it is closely supervised. Up until very recently the Iraqi side of this border was controlled by ISIS and it is still not recommended that any foreigner attempts to cross here.

Syria to Iraq

There are two border crossings between Iraq and Syria: one between Qusaybah on the Iraqi side and Abu Kamal on the Syrian side, and the other between Al Walid on the Iraqi side and Tanf on the Syrian side. Both are currently closed.

By rail

First mooted in 1914, the international service between Baghdad and Istanbul (and beyond) has a long, chequered history with many interruptions. The latest attempts to resume the service in 2010 were briefly successful, but it has now closed again due to the civil war and insurgency in Syria.

When to visit Iraq

All visitors to Iraq must remember that nothing is certain, nothing is guaranteed. The arrangements are often chaotic. This is not a country for you if you want everything to run to plan. Most of the historical sites remain; everything else, especially the political situation, can change without warning.

Climate

The best months to visit Iraq are the cool, temperate months: April, May, September, October and November, when the weather is very pleasant and warm enough to enjoy sightseeing. December, January and February tend to be cold with rain. In the mountain regions of Kurdistan heavy snow falls during the winter and the temperature can plummet, dropping below zero. The summer months (June, July and August) are very hot, often reaching temperatures as high as 50°C.

Public holidays and festivals

There are two main types of holidays: those in the solar calendar and those relating to the lunar calendar (ten days or so less than the solar year and linked to the sighting of the new moon). On public holidays ministries and government offices are closed. Businesses may also close. If the holiday falls at the weekend (Friday or Saturday), then the next working day is taken as the holiday.

The lunar calendar dictates the days of major festivals like Eid and Ashura so be sure to check before you travel as dates change every year.

What to see and do in Iraq

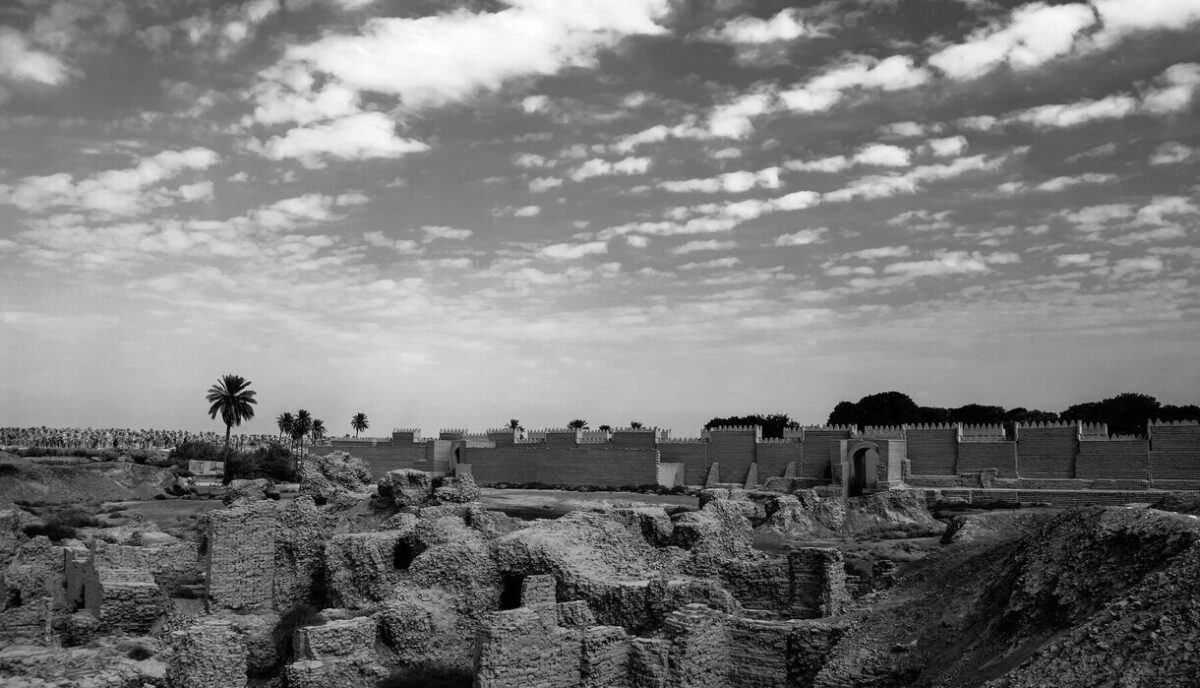

Babylon

‘Babylon the great, Mother of Harlots and the abominations of the earth’, so it sayeth in the book of Revelation in the Bible. The Babylon that has left its imprint on the history of the world is the Babylon from the time of Nebuchadnezzar II onwards – two centuries of glory and decadence when the arts and sciences flourished and when there was an unprecedented boom of prosperity. Babylon was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019.

The site is a large one. It is a mixture of the surviving remains of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon and extensive modern reconstruction and restoration. Saddam Hussein reconstructed huge parts of Babylon, including Nebuchadnezzar’s Palace, until it became the most-restored site in Iraq. Bricks inscribed with Saddam’s name adorn the site. He also built his own palace on a mound overlooking the site and the river.

The centre of the ancient city is an appropriate place to begin a tour of the site, behind the two-thirds-sized copy of the Ishtar Gate. Behind this gate is a walled quadrangle, adorned with freshly restored murals depicting ancient Sumer. Here also is the restored museum and disused souvenir shop. (Although somewhat tacky, in the 1980s and 1990s, it was one of the few places in Iraq where you could buy interesting cards, stamps and copies of brick tiles, glazed and unglazed. Little did we know then the fate that awaited the site in the future.) Leaving the quadrangle through the facing gate, you come to the steps and path leading to the famous Processional Way. Positioned alongside the rebuilt palace (which is to your left) and high off the excavated ground, it is fenced off by metal railings which have been in place undisturbed for many years (despite what has been said in the press about damage sustained during the recent conflicts, it does not seem to me to have been disturbed over the last 30 years). The original roadway, made of stone slabs coated with bitumen, does not seem to have changed and a few slabs have visible inscriptions on them. The Processional Way continues until it reaches the original Ishtar Gate. To the left of the Processional Way is the vast and amazingly rebuilt Palace of Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon. Some of the remaining original palace wall foundations still contain inscribed bricks carrying his name. There is an entrance here into the palace. On the right-hand side of the Processional Way is a temple building dedicated to the mother goddess Ninmahi. Once restored, this building is now in great need of repair again, although even in its current state, it gives a good impression of what a Neo- Babylonian temple would have looked like in this city.

From here steps descend to the Ishtar Gate, the foundations of which are still covered with the original decorations of bulls and dragon-like chimeras (composite animals with the physical attributes of a snake, lion and eagle). These bricks are unadorned reliefs, not glazed or painted. The second gate or upper part on these foundations was originally finished with beautiful glazed-brick panels depicting bulls, dragons and lions (the symbol of Ishtar). However, these were dismantled and taken in thousands of pieces to Germany after World War I by the German archaeological team that excavated Babylon, and painstakingly reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

This notwithstanding, the foundations are still an amazing sight and, in the right light, the terracotta bas-reliefs situated on the walls make for magnificent pictures. As mentioned elsewhere, the high water table has always caused problems here and in 2013 urgent work was carried out on the site to prevent this rising further and damaging the remains. During this work, and some 6m down from what appeared to be the original ground level, archaeologists uncovered yet another bas-relief chimera in line with the others. Could this newly revealed level mean that there is a much older and more extensive gate still waiting to be uncovered?

The Babylon site has always suffered a lack of maintenance, with insufficient time and money being spent on it. Now, this is being recognised. It is not easy to identify any actual war damage caused by the American forces. The looting of the museum and the removal of ancient inscribed bricks from the walls of the palace was carried out by gangs of locals.

To obtain the best from the site, read, read and read. There are so many books and so much internet material available about the past and present history of Babylon. They will enrich your visit.

Baghdad

Richard Coke writes in Baghdad: The City of Peace (1927)that: ‘In Iraq all major roads lead to the capital, Baghdad, a city that has risen like a phoenix from the ashes many times after being devastated by floods, fires and brutal conquerors. Despite its ever-changing fortunes, the city has seldom lost its importance as a commercial, communications and cultural centre.’

Located in the heart of the historic Tigris–Euphrates Valley, Baghdad began life as a series of pre-Islamic settlements. In the 8th century it was transformed into the capital of the Muslim world and remained a cultural metropolis for centuries. But the story of the City of Peace is largely the story of continuous war. Where there is not war, there is pestilence, famine and civil disturbance. Such is the paradox which cynical history has written across the high aims implied in the name bestowed upon the city by her founder.

In 1258, after its destruction by Mongol invaders, the Persians and the Turks vied for control of the city, which was finally incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1638 as the vilayet of Baghdad, an important provincial centre. In 1932 it became the capital of modern Iraq.

What to see and do

Iraq National Museum

The looting of the Iraq Museum in April 2003 was the story of a cultural genocide. ‘If a country’s civilisation is looted, its history ends,’ commented Riad Muhammad, an Iraqi archaeologist. The museum, which first opened in 1923, occupies an area of 4,700m². It was expanded continually until 1983, culminating in 28 large exhibition halls, with displays pre-dating 9000BC and reaching right up to the Islamic era. The museum’s collections included some of the earliest tools ever made, gold from the famous Royal Cemetery at Ur, and Assyrian bull figures and reliefs from the ancient Assyrian capitals of Nimrud, Nineveh and Khorsabad.

Eventually, many of the objects looted from the museum were accounted for. Refurbishments are still continuing: the Islamic Halls and the Assyrian Halls are basically complete, as is building work on an annex at the entrance. Up until the beginning of 2015 the museum was open by invitation only, but it reopened to the public in February of that year and took the next step in its rehabilitation of becoming one of the world’s great museums.

The British Museum has assisted the Iraq Museum with conservation, archaeological and curatorial assistance, as have other museums across the world. This inspires self-confidence and provides a fresh impetus to the study of ancient Mesopotamia.

Thankfully, the pessimistic view of the museum after the looting has been overtaken by optimism and the resurgence of culture and the museum has begun to blaze forth again.

The Abbasid Palace

This remarkable building on the corner of Bab Al-Moazam Bridge and Al-Rashid St/Ahmedi Square with its beautiful arch is a fine example of Islamic architecture. It was constructed during the reign of Caliph al Nasser Lidnillah (1179–1225).

The only Abbasid palace left in Baghdad, it has a central courtyard and two storeys of rooms, with beautiful arches and muqarnases (ornately decorated cornice supports) in brickwork, and a remarkable iwan (a rectangular vaulted hall, walled on three sides with the fourth side open) with brickwork ceiling and façade. When it was partly reconstructed in recent times another iwan was built to face it. Because of the palace’s resemblance in plan and structure to Al-Mustansiriya School, some scholars believe it is actually the Sharabiya School, a school for Islamic theology built in the 12th century, mentioned by the old Arab historians.

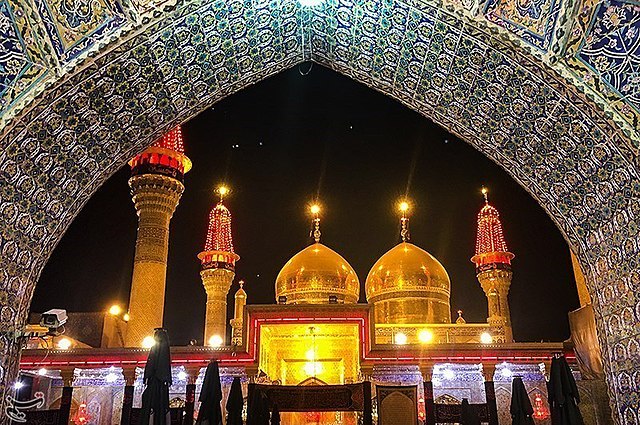

Kadhimiya Mosque

In the northern neighbourhood of Kadhimiya about 5km from the centre of Baghdad on the banks of the Tigris, Kadhimiya is one of the oldest districts in Baghdad.

Today, Kadhimiya is home to the largest Shia mosque in Baghdad. The monumental entrance to the sanctuary is dominated by two gilded and glowing domes and four impressive minarets all coated with gold. A further four smaller minarets are also gold coloured. Entering the holy shrines, one is overwhelmed by a feeling of majesty and amazement.

Kadhimiya Mosque and Shrine has today become one of Islam’s architectural wonders, and the mosque is always very crowded, thronged with Shia pilgrims from all over the Islamic world.

Jwad Selim’s Nasb Al-Hurriyah (Freedom Monument)

Located on the east side of the Tigris near the Army Canal 4km from Fardous Square, this extraordinary monument of blue domes was designed by Ismail Fattah Al-Turki and built by Mitsubishi in 1983 as a shrine to the million or so Iraqis killed during the eight-year war with Iran. Set by two lakes, the shrine is imposingly huge.

In Saddam’s time there were glass cases full of belongings of the dead including pens, nail clippers, letters home, glasses and dog tags. Today it has become a monument to Shia and Kurdish victims of Saddam’s regime. Gruesome mannequins display firing-squad executions and the unearthing of mass graves.

The monument is not an easy place to enter as special police permission is required and in the past groups of tourists to visit found the interior completely locked. Although things have relaxed slightly recently, the monument still does not attract many local people.

Al-Zawra Park

A family-friendly place, Al-Zawra Park feels very secure. The park has two entrances, one from Al-Zaytoon Street (which is less crowded), the other at the side of Al-Rashid Hotel. The park is home to the Middle East’s second-largest Ferris wheel, which is 60m high and has 40 cabins with an overall capacity for 240 people.

The amusement park has rides including the Happy Swing, Gravity, Pirates, Family Ship and Aerial Slides, and other roller coasters and water rides. If you visit in March you will be able to enjoy the annual flower festival where you’ll see (and smell) some of the best roses in the world. There is also a small zoo where a rare white Bengal tiger cub was born in 2013, and a lake with boat rides.

Where to stay in Baghdad

Baghdad has a wide range of accommodation, from five-star establishments to modest family-run hotels. One of the best-located hotels, the Golden Tulip (formerly the Al-Rashid) Hotel in the international zone, has recently been refurbished to very high standards and caters mainly for international businesspeople. You should note that many Baghdad hotels still don’t seem to have their own websites and there is no information generally available about prices.

Virtually all the hotels in the luxury and upmarket range can arrange airport pickups – just ask (and ask the price, if any) at the time of booking.

Getting to Baghdad

Baghdad’s airport is located 16km west of the city and there is a complicated entry system for passengers due to the strict security currently in place. A number of airlines fly to Baghdad airport, such as Iraqi airway which flies between London Gatwick & Baghdad via Ankara, Minsk or Moscow & Najaf via Amman. Emirates offers daily flights from between Baghdad & Dubai, plus frequent services from Basra.

Baghdad Central Station (Damashaq Sq) is the main railway station in the city and the largest in Iraq. Built by the British it is one of the best pieces of colonial architecture anywhere. Currently one daily service operates to Basra and back again with departures at 18.20, arriving in Basra at 05.30 the following morning. The service is slow and was in the past subject to attacks on the line. Subsequently, it has not been popular, but frankly it is very cheap by international standards.

A network of well-paved roads connects Baghdad with all parts of the country. Travellers are advised to exercise caution when travelling to and from Baghdad by bus, as despite the good road networks buses and bus stations can be targets of suicide bombings. In the past the Nahda bus station in Baghdad (from which buses depart to the mainly Shia cities of the south) has been the target of car bombings and suicide bombers.

Basra

Basra vies with Mosul as Iraq’s second city and is the principal port of Iraq. The city is penetrated by a complex network of canals and streams. These canals were once used to transport goods and people throughout the city, hence the misnomer ‘Venice of the East’ ascribed to Basra.

Today the drop in the levels of water and the extreme pollution of the waterways has made such use impossible. The budding port of yesterday has diminished and moved south of the city centre, and the Shatt Al-Arab is no longer so crowded with large shipping and boats scampering in all directions.

What to see and do

Ashar

Ashar is the heart of the city, the old commercial centre, home to the merchants of the 18th and 19th centuries. Situated one street north of the bazaar area, its covered bazaar and mosque mark the end of the narrow creek that links it and the river to Old Basra.

Today the older parts of Ashar are still attractive. A few of the beautiful old-style houses with walled gardens and balconies leaning over into the narrow streets remain with beautiful wooden façades in the style of old Arab architecture (called Shanasheel). They have character and are worth wandering through – a delight to see, giving you an idea of what Old Basra must have looked like. They are quite extensive: explore some of the alleyways behind the houses and note the old shutters and doorways and interestingly shaped windows; the shops smelling of spice, herbs and coffee, and the old-world atmosphere that pervades there.

Scattered in this area are also mosques and churches. The churches are very difficult to gain admission to, not surprising considering the persecution Christians in this area have been, and are still being, subjected to.

Central Bazaar

Head towards the bazaar area in the direction of the Shatt Al-Arab where you will find the many streets of the Central Bazaar. Although crowded, the myriad streets are full of almost everything that a port city would import from around the world.

Saddam Hussein’s Palace Area

Foreign visitors need to show their permission document to enter. It may be possible to obtain permission from the military by telephone, but be prepared for a long wait. If you can gain admission the palace area is well worth a visit.

There are four major buildings, with many smaller outbuildings. One palace has been taken over by a major TV centre, so is not open to the public. But the other palaces, in various states of dereliction, are viewable. Occupied by British troops when they seized the city, they initially suffered little damage, but were looted and vandalised after the British left.

The modern interior woodwork, ornate plaster ceilings, fine glass and general design, albeit larger than life, is completed with superb workmanship. The design of the exterior doors and lanterns are in harmony and the fine bas-reliefs in stone are reminiscent of Mussolini’s 1930s architecture.

Basra Antiquities Museum

Opened on 27 September 2016, it heralds a new start for culture in the region and Iraq in general. Although originally only including one gallery, this had grown to three by 2019. Assisted by the British Museum and others, it will provide training for Iraqi archaeologists and collection facilities for a new generation of young Iraqis. Work is underway to turn the whole area into a cultural centre. ‘It will be the principal museum in southern Iraq and we hope people will look to it as a model museum in the region,’ said John Curtis, keeper at the British Museum, but work is progressing slowly and it will take a long time to be completed.

Imam Ali Mosque

The Al-Imam Ali ibn Talib Mosque was the first mosque to be built in Iraq at the beginning of the Arab conquests, and the first mosque outside the Arabian Peninsula. It is an important place for pilgrimage as Imam Ali prayed here.

The mosque has been rebuilt many times, the latest reincarnation being completed by Saddam Hussein. All that is left of the first mosque is a remnant of the minaret and the columns and slabs of the original courtyard which faithfully reflect the very first mosque of Muhammad in Medina. The mosque is controlled by the Mahdi militia and it is absolutely forbidden for women to enter unless clad in the abayah provided.

Where to stay in Basra

Basra lacks good, European-style, reasonably priced hotels, and some of the top-range hotels will use this fact to try to rip off customers. You will find that in some hotels room rates fluctuate dramatically, and you can be quoted from US$200 to US$800 for the same room depending on the season or if they are hosting a conference in the hotel or not.

Around and behind the Basra International Hotel are many mid-range and budget hotels and restaurants. These mainly attract local Iraqi and foreign workers so don’t tend to advertise internationally or have websites. Many are heavily, or even fully, booked for months in advance, being the only places to stay for the influx of businesspeople and workers in Basra. Standards in these hotels vary enormously. The best advice is to visit the area, check availability and price in person, and view the room and facilities before making a booking.

Getting to Basra

Basra International Airport is located 20km northwest of Basra city. Emirates offer frequent services from Basra and Dubai. FlyDubai have flights between Baghdad/Basra & Dubai, and Fly Baghdad offer flights between Baghdad/Basra & Minsk/various hubs in the Gulf.

An overnight train service from Baghdad departs daily at 18.30 and is scheduled to arrive at 06.10 the next morning; however, delays are common. The train usually carries a restaurant car and sometimes ‘tourist class’ carriages. The railway station is a somewhat bare, basic building with minimum facilities. Tentative attempts have been made to promote tourism on this route; however, the infrastructure is not yet in place for this to attract international tourists, although it is used by local visitors and offers a good, inexpensive alternative to driving or flying.

Erbil

Erbil (known in Kurdish as Hewler, seat of the Gods) and today the home of one million people is one of the fastest growing cities in Iraq and the Middle East. The seat of government and power in Kurdistan, it is modernising and developing as a regional capital. The city has transformed itself and sets an example to the rest of Iraq with its cleanliness and modernity.

Ankawa, a Christian suburb of Erbil, is a vibrant area of restaurants, cafés and bars and the amazing Qyesariyeh Bazaar, selling everything from fabrics and jewellery to cheese made from sheep’s milk, is one of the few remaining historical areas one must absolutely visit. The ancient citadel, recognised as a historic site by UNESCO, is being renovated and, for the first time in its history, is uninhabited.

The freedom of movement and the nonchalant Dubai-ish atmosphere in the more modern parts of the city is, at first, a tonic after the wearying security restrictions which prevail in the rest of Iraq. But travellers have to decide for themselves whether the attraction of a large, modern city is what they are looking for in Kurdistan.

What to see and do

The citadel of Erbil

Located in the centre of the old city, this vast citadel covers an area of 102,000m2. It is a round construction built upon a 26m-high tel, a historic mound of many layers of historical settlements dating from ancient times.

The first village was established here around the 6th millennium BC and has been continually inhabited ever since. The citadel has seen the reign of many historic civilisations, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian. Other powers, including the Achaemenids, Greek, Parthians, Seljuks, and Sassanids, also dominated the citadel before it was finally conquered by the Ottomans.

Sitting at the south entrance to the citadel is an imposing statue of Mubarak Ahmad Ibn al-Mustawfi (1167–1239), a former minister and historian from Erbil who rose to fame chronicling the history of this ancient city. From here there is an impressive view over Shar Garden Square and the rooft ops of the covered Qyesariyeh Bazaar below.

Until 2006, the interior of the citadel contained more than 600 houses and the area was abuzz with daily life. Today, with restoration work by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in co-operation with UNESCO going on, an eerie silence reins. The main gate overlooking the town, which was rebuilt by Saddam Hussein, has been removed and a fresh gate, more in keeping with the original one, built in its place. The walls of the citadel are slowly being repaired and its inner historical houses are being reconstructed and refurbished under the auspices of the UN and converted into various smaller museums.

Qyesariyeh Bazaar

South of the citadel, this covered market is the oldest in Erbil. The name (from Roman ‘Kaiser’) is common in this part of the Middle East and refers to the importance and value of the goods sold under the bazaar’s vaults.

You enter through a number of alleys surrounding it, and walk through the maze of narrow paths between the shops. Many of the alleys contain similar products: clothing, shoes, jewellery, cloth. In the northeast corner is a north–south alley selling a variety of honey, yoghurt and cheese.

But the one product that thrives in the bazaar is gold. Displays are filled with pure 18-, 22- or 24-carat gold; you really can’t find anything less than that. In Erbil, when a couple get married it is traditional for their families to go to these stores to pick out the ring, necklace and bracelet for the bride.

Shar Garden Square

In front of the Qyesariyeh Bazaar just below the citadel, this modern public square and esplanade is complete with fountains, brick arcades and a clock tower modelled on London’s Big Ben.

A favourite haunt of Erbilites with its narghile cafés and tea shops, the square attracts locals of all ages and during the summer is alive with tourists from the southern provinces. Part of Erbil’s urban redevelopment plan, the square offers a great view of the citadel and its many fountains cool the arid air, bringing a refreshing respite from the bustling bazaar.

Minaret Park and the Muzzafariya Minaret

A short walk or taxi ride southwest from the citadel, this is without a doubt the most architectural of Erbil’s green spaces. Minaret Park offers up an eclectic fare of circular terraces, Etruscan columns and cascading fountains. Lit up like an urban wonderland on summer evenings, it is a popular destination for the city’s youth and young families taking in the cool evening air. Well-planted walkways and shaded groves provide a romantic backdrop for promenading couples and a raised-terrace café offers narghiles and welcome refreshments.

Tucked away in a quiet corner of the park is the 36m-high Muzzafariya Minaret, dating back to the reign of King Muzzafar al Din Abu Saeed al Kawkaboori (brother-in-law to the crusader-battling Saladin) in the late 12th/early 13th century. The ornate brick minaret has an octagonal base decorated with two tiers of niches, which are separated from the main shaft by a small balcony, which is also decorated. It is all that now remains of the city’s medieval growth beyond the confines of the citadel.

Shanidar Park

Connected to Minaret Park via a cable car is Erbil’s oldest permanent exhibition space. Although much of the artwork on display in the gallery’s regularly rotating exhibitions doesn’t stray too far from what you might expect from a provincial art space showcasing mainly student works, there are occasional treasures to be discovered.

A visit to the gallery can also provide an opportunity to meet local artists who, language-permitting, will be delighted to talk about their work and experiences. Don’t be surprised to find queues after sunset in the summer months when locals turn out in swathes to take in the cool evening air and do a little people-watching of their own.

Sami Abdulrahman Park

The biggest and greenest of Erbil’s parks, Sami Abdulrahman is situated west of the citadel on 60 Meter Street, opposite Kurdistan’s Parliament and Council of Ministers buildings. It is a favourite spot among the residents of Erbil for family picnics and a welcome refuge from the hustle and bustle of the city.

The park is divided into well-mapped sections with leafy walkways, rolling lawns and flower gardens, a small amphitheatre, and a health club complete with open-air swimming pools, a gym and a sauna. During the summer months, the park stays open long after sunset and this is when it is busiest. It has several well-equipped play areas for children, lakes offering boat rides, fountains and a garden restaurant with a basic but well-prepared selection of local culinary delights.

Formerly a large military complex, the park takes its name from a former prime minister killed in a 2004 suicide bomb attack that claimed around a hundred lives. The large Martyr’s Monument in the park dedicated to the victims of the attack provides a solemn reminder of Iraq’s bloody history and Kurdistan’s struggle for autonomy. A poignant inscription on the monument reads simply: ‘Freedom is not free’.

Where to stay in Erbil

The last few years have seen a dramatic increase in both the number and standard of hotels in Erbil. Accommodation prices are significantly higher than you would expect to pay for similar accommodation elsewhere, due in part to the influx of business travellers and NGOs.

It is always worth trying to negotiate the price or asking for a discount, especially during low season and especially as an individual traveller. Budget hotels (under US$20) are best to be avoided, if possible. Doubling this amount for two people per night will get a comfortable lower mid-range room with a breakfast.

Getting to Erbil

Most flights operating from Europe and the Middle East fly directly to Erbil International Airport, located 7km northeast of the city.

To/from Europe, Austrian Airlines operates a daily flight to/from Vienna. Lufthansa has two services per week to Frankfurt. National flag carrier Iraqi Airways flies once a week to Copenhagen, Düsseldorf and Frankfurt. There is also an extensive network of flights to destinations in the Middle East. FlyDubai fly daily to Dubai.

Erbil International General Terminal near Family Mall is the main bus station with regular shared taxi departures to Duhok, Mosul and Shaqlawa as well as buses to Turkey and Iran. From here there are daily services to various destinations in Turkey, including Diyarbakir (10–15hrs) and Istanbul (36–48hrs) operated by Cizre Nuh Buses, Can Diyarbakir Buses or Best Van.

Sulaymaniyah

Sulaymaniyah is a rapidly developing metropolis of around 700,000 people, but in the mid 20th century, this overwhelmingly Kurdish city and former capital of Iraqi Kurdistan had merely 35,000 inhabitants.

It is the most vibrant and cultural city in the autonomous region and residents here and in the surrounding governorate – more than anywhere else in Kurdistan – opt for traditional clothes, in particular Kurdish baggy trousers fitted at the ankles (called sharwar in Kurdish). Sulaymaniyah University, established in 1968, is a renowned centre for the study of Kurdish language and culture and Kurdish poetry festivals are regularly held here amid much fanfare.

Sulaymaniyah is also an important commercial centre with close economic ties with Iran. The Kurdish Sorani dialect spoken here is the same as across the border in Iranian Kurdistan and many Iraqi Kurds travel to Iran for medical treatment, while Iranian Kurds come here for shopping trips and holidays. Sulaymaniyah’s natural setting amid the surrounding mountains and pleasant weather makes it an attractive holiday destination, especially among Iraqi Arabs escaping the summer heat of southern Iraq.

What to see and do

Sulaymaniyah Museum

The second-largest museum in Iraq after the National Museum in Baghdad, this archaeological museum is home to a vast collection of ancient artefacts from around Iraq and the region, many of which are several thousand years old, although many are just copies.

The main reason to visit is the collection of 152 stone blocks from the Paikuli Tower bearing Sassanid inscriptions. Written in Middle Persian and Parthian languages, the inscriptions and the tower were built by Sassanid king Narseh (293–303), son of Shapur I, in honour of the former’s accession to the throne. Since 2006 the inscriptions have been studied by a team of archaeologists led by C G Cereti from the Sapienza University of Rome. The Iddi-sin stela dating to the Old Babylonian period (2003–1595BC) is another true highlight; the 108 lines of cuneiform inscriptions carved into it celebrate the victories of the King of Simmurum, one of the ancient Mesopotamian city states.

Amna Suraka Museum

Notoriously known as the ‘red house’ owing to the red colour of the security buildings used by Saddam Hussein’s regime, this former detention centre, which was in operation from 1979 to 1991, is now preserved as a memorial and museum, showing how its detainees lived. The museum provides information about the genocide campaigns against the Kurds in Iraq. Shattered buildings still standing at the site poignantly reflect the atrocities, as do sketches and pictures scratched on the walls of former cells.

Over the years, thousands of Kurdish activists, students and anyone who Saddam deemed to be reactionary to his regime and policies were detained, tortured and even killed here. In the grounds there is also a small ethnological display showing a typical Kurdish home, a hall of mirrors and a display of taxidermy. Some of the bullet-scarred buildings here also show the last stand of Saddam’s police and troops in the city when it was reclaimed by the Kurds. At the furthest end of the site a former garage for Baath Party members’ vehicles has been converted into a modern gallery and exhibition space.

Azadi Park

Located north of Amna Suraka Museum, this sprawling public space had, up until 1991, functioned as a military base of the Baath regime. It is now the largest city park in Sulaymaniyah and a place for a snack or a refreshing drink on a hot summer day.

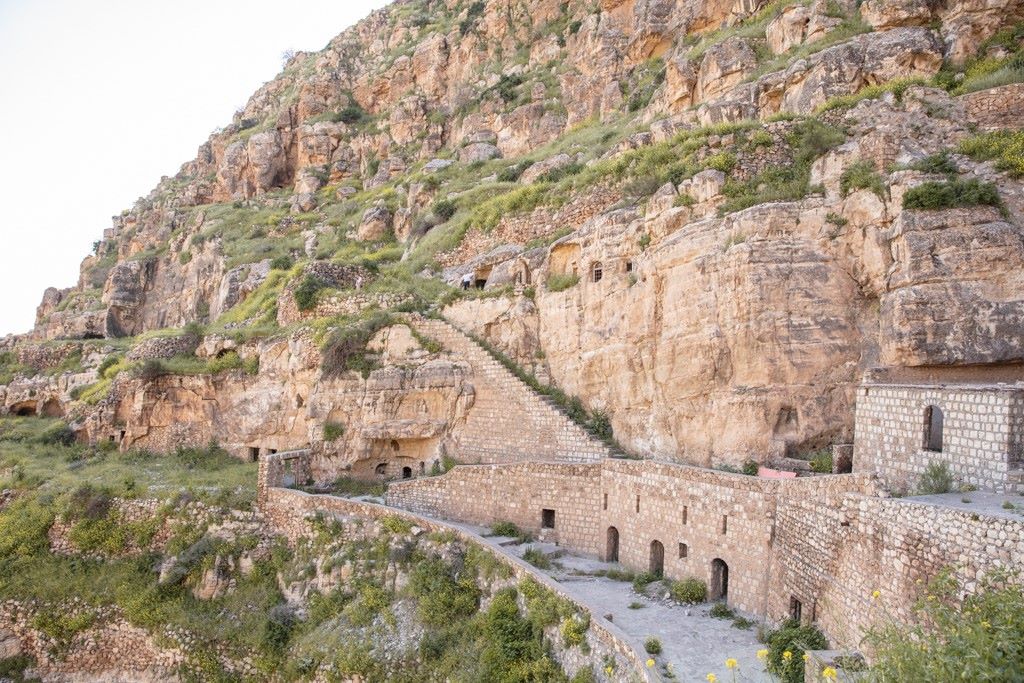

Kunara

The area south of Sulaymaniyah, in particular in the Zagros Mountains, is home to numerous archaeological sites of immeasurable importance. Although not necessarily visually spectacular, these offer a unique insight into the history of this region that had for years remained hidden due to Saddam Hussein’s ban on carrying out exploratory work in Kurdistan.

A mere 10km southwest of Sulaymaniyah, on the right bank of the Tanjaro River, lies the vast 7–9ha archaeological site of Kunara. First excavated by the French Mission archéologique du Peramagron in 2012, the site is believed to date to 2200bc and belonged to an unidentified kingdom, possibly Lullubi mountain people, settled here at the time of the Akkadian Empire. Although excavations are ongoing, the work carried out to date has led to the discovery of ancient stone structure foundations as well as cuneiform tablets. Locating the site independently is not easy – best to take a local guide.

Where to stay in Sulaymaniyah

Sulaymaniyah has a good range of accommodation options, though sadly very few decent budget hotels. The city centre, in particular around Mawlawi Street and the bazaar, is awash with one-star hotels – some of dubious standard, others passable for a budget traveller. Do not hesitate to ask for a discount, especially during the low season, and always check out the room before you strike a deal.

Getting to Sulaymaniyah

Sulaymaniyah International Airport is just west of the city near Bakrajo and has regular connections to Doha, Dubai, Istanbul and Tehran with Qatar Airways, FlyDubai, Turkish Airlines and Qeshm Air. Iraqi Airways have regular flights from/to Baghdad and Basra. Iran’s Mahan Air also regularly fly to Tehran.

The journey from Erbil to Sulaymaniyah takes approximately 3 hours and goes past the Dukan Lake. Although expansion works have been completed, the road should be avoided after dark due to heavy commercial traffic. Sulaymaniyah has two main bus/taxi terminals: Garage Halabja for travel to Halabja and the region’s eastern destinations, and Garage Baghdad for Erbil and beyond, including to Kirkuk and to the rest of Iraq.

The Shrine Cities – Najaf and Kerbala

Najaf

Home to the Holy Shrine of Imam Ali, the fourth caliph and son-in-law of the Prophet, resplendent with its golden dome and minarets, Najaf is a major city of mosques and shrines.

There is no quarter or street without a mosque, either small for the locals or large and attended by visitors to the city. The city’s large cemetery (Wadi Al-Salam) is considered the holiest and most sought-aft er place for burial among Shia believers. Najaf is also one of Islam’s most important seminary centres for the training of Shiite clergymen (al Hawzah al Ilmiyyah), and has many religious schools. Every year millions of pilgrims visit the Holy Shrine of Imam Ali, whose shining golden dome is visible from a distance of 75km away.

What to see and do

Shrine of Imam Ali

Enclosed in a mosque named Al-Haidariya Shrine is the spectacular Shrine of Imam Ali. Built in the same style as those of Kerbala, Samarra and Kadhimain, it comprises a rectangular enclosure surrounding a two-storeyed sanctuary, containing the tomb, with a great dome over it.

The most prominent and visible part of the shrine is its resplendent golden dome. Approximately 25m from the roof of the shrine, its diameter is about 16.6m. Wrapped in tiles of gold foil, the dome is surrounded by a belt of gold Koranic verse against a background of startling blue enamel. The whole edifice stands on a square-shaped ornate structure. At the eastern side of the shrine are two golden minarets (that to the north is 29m high, the one to the south is 29.5m) each made of 40,000 gold tiles, inlaid in some places with blue enamel.

Within the shrine the surrounding walls have many open rooms or iwans that are laminated with Kerbala mosaic which in turn is decorated with a number of Koranic verses, pictures of plants and beautiful inscriptions. Some of these inscriptions contain valuable historical information which is considered to be a record of rich Islamic heritage.

The atmosphere is not so emotionally charged as in Kerbala. It feels more mature, more respectful to Allah (God) and Imam Ali as his servant. You have to go through the usual routines of checking in cameras, mobile phones, etc, and the checking of women’s clothing, but the welcome is genuine.

Wadi Al-Salaam Cemetery

The Peace Valley Cemetery, known as Wadi Al-Salaam Cemetery, is to the north of the Shrine of Imam Ali, beginning at the end of Al-Tossi Street. It is on UNESCO’s tentative list of World Heritage Sites, highlighting its significance as one of the largest cemeteries in the world. It includes the remains of millions of Muslims and dozens of scientists, guardians and people of faith as well as the graves of prophets Salih and Hud.

Because of the merit accorded to being buried in this cemetery and the honour of being interred near the remains of Ali, Muslims come from all over the world to conduct the funerals of departed family members in Najaf in order for them to be entombed in this cemetery.

Al-Hannanah Mosque

This is one of the most revered mosques in Najaf and covers about 7,400m² In the middle of the mosque is the place where it is believed that the head of Imam Hussain was put after his martyrdom in 680AD. Historical references also indicate that the body of Imam Ali passed through this location on its way to Najaf. The shrine has been renovated and extensively reconstructed.

Najaf Sea

To the south of the old city near the Safi Safa Shrine in an expansive area with very beautiful scenery, you can see the natural depression which once contained the Najaf Sea. Nothing remains now of the sea itself except its name; historians think that it was probably a land-locked lake whose waters finally disappeared in the 19th century.

It is said that in its heyday the Najaf Sea was used by ships carrying goods and people and that the remains of many shipwrecks were found on its shores as the waters receded and evaporated. Today the Najaf Sea is considered to be one of the most fertile agricultural areas in Najaf, with fields of vegetables and glades of palm trees.

Where to stay in Najaf

Although hotel accommodation is not limited, given the huge numbers of pilgrims visiting Najaf every day, bookings should be made in advance wherever possible. Many new hotels are being constructed to accommodate the influx of pilgrims, but despite this Najaf is still underdeveloped in terms of accommodation, restaurants and other tourist facilities. You will find numerous smaller, local hotels on every street in Najaf. Classified as ‘second rank’ hotels, their clientele is almost exclusively pilgrims or local Iraqis, travelling in family or larger groups. These hotels are basic, often with mainly family rooms and lacking Western-style toilets. Dining rooms are frequently communal-style and often segregated into male and family areas.

With its strict adherence to Sharia principles (including no alcohol, a strict dress code for women in public, frequent segregation of the sexes and constant security checks even when walking along the streets), Najaf is not the most comfortable or relaxing place to visit.

Getting to Najaf

Located on the eastern side of the city, Al-Najaf International Airport. As of June 2019, Najaf Airport was served by an extensive list of airlines. It is possible to fly directly into Al-Najaf International Airport from the UK and the following airlines have direct flights into the airport from their home countries – Turkish, Qatar Airways, Kuwait Airways, Air Arabia, Iran Air, Middle East Airlines, Gulf Air, Royal Jordanian, Cham Wings Airline and FlyDubai. Iraqi Airways have domestic flights to Najaf from Baghdad, Erbil, Suleimaniyah, Mosul and Basra.

Kerbala

The first major Shrine City on the route south towards Basra is Kerbala. The name Kerbala is derived from the Babylonian word kerb (a prayer room) and El, Aramaic for God – hence God’s temple. Kerbala’s Shia sanctuaries are objects of great veneration and the city contains the shrines of Hussain ibn Ali, son of Imam Ali, and Abbas, Hussain’s half-brother. Hussain is known among Shia believers as the Prince of Martyrs (sayyid al shuhada) because he was killed in his challenge to the accession of Muawiya’s son Yazid to the caliphate.

Kerbala emerged as a focus of devotion, particularly for Persian Shia believers. The city has been strongly infl uenced by the Persians, who were the dominant community, making up 75% of the population at the turn of the 20th century, when there were around 50,000 people in the city.

What to see and do

The town is split into two: Old Kerbala, famous for its shrines, and New Kerbala, the residential district containing Islamic schools and government buildings. Th ere are more than 100 mosques and 23 religious schools in the city, the sole reason for travellers to visit.

The mosques of Hussain and Abbas stand out on their own as islands in the middle of a city whose activities are centred around the wants and needs of the pilgrims. Hussain’s Mosque and Shrine is surrounded by a wall with eight gates. The main gateway is surmounted by a clock tower decorated with glazed blue and gold earthenware. The three small bulbs on the dome, which is covered in gilded copper, indicate the importance of the mosque.

The second major shrine in Kerbala is that of Abbas, Hussain’s half-brother. The Abbas Shrine has nine gates decorated with glazed tiling leading into the mosque. In the middle of the shrine is the tomb of Abbas, over which there is a huge dome with Koranic verses and the Prophet’s sayings inscribed in gold. In the middle of the shrine is the tomb of Abbas, over which there is a huge dome with Koranic verses and the Prophet’s sayings inscribed in gold.

Where to stay in Kerbala

Despite there being hundreds of hotels in the city, Kerbala is still underdeveloped in terms of accommodation for the millions of Shia pilgrims who come here to visit the religious sites each year. It has no luxury hotels that meet international standards, despite the huge demand, and although hotel prices can be high, the level of quality of the accommodation can be very poor. You will find numerous small, local hotels on every street in Kerbala. Although they are classified three-stars, two-stars or one-star, these ratings do not correspond in any way to European equivalents.

Very few non-Muslims visit Kerbala as, with its strict adherence to Sharia principles (including no alcohol, a strict dress code for women in public and constant checkpoints to go through even when walking along the streets), it is not conducive to relaxation. Furthermore, apart from the shrines, there is nothing in the way of sightseeing.

Getting to Kerbala

Although the foundation stone of Kerbala International Airport was laid in 2009, with the airport anticipated to cater to the increasing religious tourism traffic, work is progressing painfully slowly.

Located 105km south from Baghdad, on Highway 8, the city is easy to get to as it is signposted from every direction. Note all the approach roads have outer and inner checkpoints. Security measures are fully implemented 24 hours a day.

Ur

Ur, together with Babylon, is probably the best-known city of Mesopotamia. It is a prime example of Iraq’s phenomenal archaeological sites. The wealth of modern literature and the glittering objects in museums worldwide has made this so. Ur is known locally as Tel Muqeihar or ‘mound of bitumen’, a name taken from the 18m-high ruins of the ziggurat, which dominated the otherwise desolate site. The visible remains of the ziggurat itself are of two widely different periods, an early structure built by Ur-Nammu about 2300BC having been enlarged and rebuilt by Nabonidus in the 6th Century BC.

The site of this city is huge and remarkable remains can be seen of the harbour temples and the great city wall which is an astonishing piece of work and almost oval in shape.

The third-Dynasty mausoleum contains the Royal Tombs which form the eastern limit of the great cemetery. The graves vary in date from the beginning of the Early Dynastic to the end of the Akkadian period, and were consequently superimposed and often inter-penetrating. The majority have disappeared in the process of excavating, but some of the vaulted tombs in which important people were buried still remain.

Behind the Royal Tombs are some large spoil heaps and the foundations of many ancient houses, a few of which have been reconstructed. It is claimed that this is the place where Abraham lived with his family. Walkways have been constructed between the ziggurat, the Royal Tombs and the reconstructed Abraham’s House.

The Royal Tombs are fenced off, partly to protect them, but also because their roofs are damaged and potentially dangerous to tourists. Close by the tombs you can see the ‘Pit’ or ‘Woolley’s Pit’. This 35m-deep excavation was an attempt by Sir Leonard Woolley to plumb to the ground levels of the site, and Woolley subsequently cabled a telegram to London newspapers to say that he had found evidence of the biblical flood in the pit. Plans are still current for some minor archaeological work, but mostly the site is being planned as an important tourist and visitor centre.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Iraq

Related articles

Remembering a great adventurer.

There’s lots to see in the land between two rivers.

Discover our favourite sights along one of the most important trading routes in history.

This is a land where clay tablets, ziggurats and temple ruins shed light on life in ancient times.

An experience of the region, not as one of danger, but of friendly, hospitable people.