Iran is one of those countries where issues concerning religion and the modern world confront you at all turns and compel you to consider your own stance.

Hilary Smith, author of The Bradt Guide to Iran

It is impossible to return from a visit and not feel that, while seeing magnificent historic architecture and evidence of ancient civilisations, you have also been witnessing history in the making.

Iran is the birthplace of one of the greatest civilisations of the world, home to breathtaking landscapes and geographic contrasts.

Travel to Esfahan and wander around the magnificent Naqsh-e Jahan Square with its most splendid mosques and bazaars, visit the jewel-like gardens of Shiraz drowning in exotic flower scents, and crown your holiday with a trip to Persepolis, Iran’s most impressive historical heritage from Ancient Persia.

Iran is equally a fantastic ski holiday destination. The Alborz Mountains with the highest peak in the Middle East – Damavand – offer excellent slopes and accommodation. And before leaving, make sure to take a break in a lively café and enjoy the friendliness and warmth of the Iranian people, who will make your trip to Iran unforgettable.

As a foreign visitor, you will be struck by the friendliness, warmth and genuine curiosity of the locals throughout Iran. In other countries it is sometimes difficult for individuals within a tour group to talk with anyone other than the guide, the driver, or the hotel and shop staff, and some argue that to experience fully a country and a people, one must be an independent traveller.

In Iran this is not the case. Indeed, it could be argued that in Iran, forces conspire against the independent traveller, especially those who don’t know the language; the country is just not geared up to this kind of tourism. Everything takes so much longer to sort out, and indeed the visitor is so dependent on Iranians helping that the term ‘independent traveller’ is almost a misnomer. Group travel in Iran can and does open doors in more senses than one – it cuts down endless queuing and waiting for buses and the like.

For more information, check out our guide to Iran

Food and drink in Iran

Food

Iranian cuisine is one of the world’s finest, an intriguing mixture of sweet and sour that owes nothing to the Chinese version. Iranian khoresht – stewed dishes of meat and fruit – may sound uninspiring but wait until you’ve tried duck or chicken in pomegranate and walnut sauce (fesenjan), lamb with morello cherries or apricots, beef or lamb with spinach and prunes (aloo) and chicken and zereshk (barberries), etc. Delicious.

Also try abgoosht (literally water-meat), or dizzi stew served in a jug-like container with a pestle and commonly available even at bus station restaurants. This is a concoction of slowly simmered pulses, meat and vegetables. When in Esfahan, try beryani, boiled lamb meat minced and fried with onion and spices. Saffron (in particular from Mashhad) itself is a very common ingredient that you will even taste in chicken kebab and rice.

White rice and bread are the staple foods. A delicious change is rice with butter slowly steamed until a crunchy, caramelised layer is formed. Traditional Iranian salads or servings of fresh mint leaves are called sofreh and traditional restaurants are then often called sofreh knaneh, meaning a ‘house of sofreh’ in Persian.

Fresh fish such as trout from the many farms, prawns and shrimps from the south and north coast, and sturgeon from the Caspian Sea are flown in every day to the major cities.

The Iranian equivalent of British fish and chips, or American hamburger and French fries, is chelo-kebab, a skewer of grilled lamb, served with plain rice, with or without a raw egg on top. There is also Iranian coleslaw, which is often available in restaurants in place of salad or in addition, and is called salad-e kalam (cabbage salad). Zorat-e mekziki (Mexican corn) is the the all-time favourite snack on sale practically everywhere in major cities.

And of course there’s the originally Shirazian sweet delight of falludeh ice, a sorbet with wispy ‘noodle’-like strands, served with lime juice and ice cream. One of the joys of visiting Iran is sitting eating falludeh, sipping tea or smoking a pipe in the attractive surroundings of a historic tea house. Gooshfil deep fried and poolaki caramelised sugar sweets are also widely popular.

Drink

All alcohol is banned in Iran although the Christian communities, in Esfahan for example, are allowed wine strictly for communion use. However, Iran’s famous vineyards are now being recultivated after most were uprooted in revolutionary zeal; the grapes are for eating, and for the production of grape juice, syrups and vinegar.

Iranian (non-alcoholic) beer is terrible, though Delster is just about palatable if well chilled. A very passable non-alcoholic ‘lager’ is Bavaria, now imported from Dubai. It’s available only in large centres at about 40,000 rials from local shops (US$1) but more in restaurants and hotels – just slightly more than the Iranian bottled beer but worth every rial.

Local carbonated soft drinks, such as cola, Fanta and Sprite, tend to sweetness, and the fruit juices, either freshly pressed or in cartons, are more thirst quenching, such as pomegranate juice, talebi (cantaloupe melon) juice, and carrot juice with a scoop of ice cream from fruit-juice shops. The refreshing, pressed-lime sodas of pre-revolutionary Iran are unfortunately no longer available (presumably because the soda isn’t) but another refreshing drink, doogh (yoghurt and water, like Turkish ayran or Indian lassi), is available.

Health and safety in Iran

Health

Before you go

It is advisable to be up to date with all primary immunisations including tetanus, diphtheria and polio – an all-in-one vaccine (Revaxis) lasts for ten years. You would also be wise to be protected against hepatitis A and typhoid. Hepatitis A vaccine (eg: Havrix Monodose or Avaxim) comprises two injections given about a year apart. The course costs about £100, but may be available on the NHS; it protects for 25 years and can be administered even close to the time of departure.

Hepatitis B vaccination should be considered for longer trips (two months or more) or for those working with children or in situations where contact with blood is likely. Three injections are needed for the best protection and can be given over a three-week period if time is short for those aged 16 or over. Longer schedules give more sustained protection and are therefore preferred if time allows. Hepatitis A vaccine can also be given as a combination with hepatitis B as ‘Twinrix’, though two doses are needed at least seven days apart to be effective for the hepatitis A component, and three doses are needed for the hepatitis B.

The newer injectable typhoid vaccines (eg: Typhim Vi) last for three years and are about 85% effective. Oral capsules (Vivotif) may also be available for those aged six and over. Three capsules over five days lasts for approximately three years but may be less effective than the injectable forms as their efficacy depends on how well they are absorbed.

Vaccinations for rabies are advised for everyone, but are especially important for travellers visiting more remote areas, especially if you will be more than 24 hours away from medical help and definitely if you will be working with animals.

In Iran

In the major cities, it will be said that the water is safe for cleaning teeth as it is heavily chlorinated (neighbouring Tajikistan and Afghanistan suffer cholera outbreaks). However, it is always safer to use bottled water both for drinking and for cleaning your teeth.

Opportunities to strip off and sunbathe are obviously severely limited in the Islamic Republic, but the force of the Iranian sun is powerful and there is comparatively little shade so avoid excessive exertion during midday hours and wear a sunhat. Women should wear theirs over a scarf. Clothing in natural fibres is most comfortable for the hotter months but evening temperatures can drop suddenly, especially in the hills, so take a light sweater too.

Take the usual precautions when walking across rough and stony ground, and through shrubbery and vegetation, against snakes, scorpions, etc. If you are entering a ruined building from broad sunlight, make a noise so that any snakes retreat.

Travel clinics and health information

A full list of current travel clinic websites worldwide is available on www.istm.org. For other journey preparation information, consult www.travelhealthpro.org.uk (UK) or http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ (US). Information about various medications may be found on www.netdoctor.co.uk/travel. All advice found online should be used in conjunction with expert advice received prior to or during travel.

Safety in Iran

Crime

Any crime carries severe penalties in the Islamic Republic. It is likely that the greatest danger you will face (other than crossing the road) is having your wallet, purse or camera snatched. Keep photocopies of the most important pages (including the visa if possible) of your passport and air ticket, and spare passport photos separately, and don’t flash money or expensive camera equipment ostentatiously. The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office has warned that bogus policemen have approached some visiting foreigners, advising that in such circumstances you should insist on seeing an identity card and inform the restaurant, shop or hotel of the incident. Remember that no Iranian policeman has the right to take or retain your passport unless you are in a police station.

Iran is very safe for women travellers. Harassment is now minimal, especially if you wear the manteau, as it is assumed you are Iranian and/or Muslim. Be aware, however, that it is very unusual for a single woman to walk unescorted in public at night. Make sure to avoid being alone in the evening in particular in the old town in Yazd, or Ahvaz and Khuzestan generally. If you do feel, however, that you are being harassed, you are strongly encouraged to bring this to the attention of other people present, in particular men (eg: a bus driver). Such behaviour is looked down upon by other members of the society. By expressing your indignation publicly you will be doing other female travellers, and yourself, a great favour. Keep in mind that harassment often happens simply because it is perceived as acceptable.

Road safety in Iran

You are more likely to be in danger if you insist on importing your car. There were 24,000 road deaths and over 80,000 injuries reported in Iran in 2006. During the first eight months of 2012 around 14,000 people lost their lives. The number of deaths, however, seems to be slowly decreasing from the peak of 27,759 deaths in 2005. Leaving aside the nightmare of Tehran traffic, which guarantees road rage and stomach ulcers, be aware that Iranian lorry and coach drivers work very long hours and that few private vehicles have reflectors or working lights and their drivers disregard every rule in the book.

Traffic does not necessarily stop at a red light, nor wait until green before setting off, with the exception perhaps of Kish and Qeshm. Regard zebra crossings as merely road surface decorations. Pedestrians take their life into their own hands crossing the road and the sight of their terror-stricken faces forms the chief entertainment for motorists. If a driver flashes his/her lights it does not mean it is safe to cross; your presence is being acknowledged, but not necessarily your continued existence on this earth. On the other hand, having started to cross, do not turn tail or break into a run; both actions constitute a personal challenge to the driver to continue the pursuit.

Personal conduct

Be aware that it is easy to break an important social convention without realising it and this can affect your safety. For instance, in summer 2004, the smoking of ‘hubble-bubble’ waterpipes (qalian) in public was banned on the grounds that it promoted ‘licentious behaviour’. Presently men can smoke in public, but it may be more difficult for women, as most traditional tea houses would not serve qalian to women or mixed groups.

If you are confronted with officialdom, do not lose your temper, shout or threaten. Be polite and apologetic if not abject. Women: forget all feminist scruples and cry. Always insist on seeing someone who speaks English (any other Western language will be difficult).

Travelling with a disability

Planning an accessible trip to Iran may be challenging, as the required information is not easy to come by. Nevertheless, the ancient beauty of this unique country can very well be enjoyed by anyone, with or without disability. Since the establishment of the Ministry of Social Welfare in the 1970s, public services for people with disabilities have improved, and many disability organisations are active to achieve general inclusion.

Travel and visas in Iran

Visas

All nationalities except Israelis are allowed to apply for a visa. Anyone domiciled in the USA should approach the Iranian Interests Section of the Embassy of Pakistan or the nearest Pakistani consulate or the Iranian Mission at the United Nations.

Those resident elsewhere, however, including US passport holders, should contact the Iranian embassy or consulate in their country of residence for information regarding the embassy’s opening times, methods of payment and exact visa application details.

Although the procedure for British and US passport holders is complex, other nationalities, including those from Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia and Italy, have fewer problems in this respect. Women without headscarves will generally be allowed onto Iranian embassy grounds, however, it is advisable and strongly recommended that you do wear a headscarf as it makes a good impression.

Since 2016 it has been possible to obtain a 30-day tourist visa on arrival in some international airports in Iran. However, visa applications on arrival are not automatic and payment in euros is preferred. US, UK and Canadian passport holders are not eligible for this option and are required to apply in advance through the embassy.

Getting there and away

By air

International Airport (IKA), Tehran, but foreigners with valid visas can also enter/exit Iran by way of various Persian Gulf states airports (eg: Abu Dhabi and Bahrain to Shiraz, Bahrain to Mashhad, Dubai to Ahvaz and Bandar-e Abbas). Sometimes officials check your baggage receipt against the tag on your luggage.

There are at present no direct flights from any American or Canadian airports. British Airways has a direct London–Tehran service. KLM/Air France and Austrian Airlines have resumed their regular flights to Tehran. Turkish Airlines fly to a number of cities in Iran from Istanbul, including Esfahan, Shiraz and Mashhad. Istanbul–Tehran flight duration is around three hours. All flight carrier options listed below, when booked in advance, should cost around £400 for an economy-class return fare.

A list of current international cities with services to and from Imam Khomeini International Airport is available on the English version of the airport’s website, which also contains useful plans showing routes through the airport, positions of banks and lists of available taxi services.

Pegasus Airlines, the Turkish low-cost airline, fly to Tehran via Istanbul with connections from various European cities.

Aeroflot have good connections to some European cities.

By road

There are border-crossing points from Turkey (via Dogubayezit); from the Republic of Azerbaijan (via Baku/Astara); from Turkmenistan (via Ashkhabad or Sarakhs); and from Pakistan.

By train

Provided you can obtain a visa there is a weekly train, the Trans-Asia Express, from Istanbul to Tehran (twice weekly in summer) leaving on a Tuesday and arriving on a Friday; The Man in Seat Sixty One provides up-to-date information on timetables, booking, prices and train facilities.

By sea

Iran can be accessed by sea from Dubai to Bandar-e Lengeh, from Kuwait to Khorramshahr and from Shahjah to Bandar-e Abbas. Ferries are operated by Valfajr Shipping with normally two departures per week. Contact one of the company’s offices to make a reservation.

Getting around

On all forms of public transport that are not pre-segreagated, and excluding planes, men will probably be asked to change their seat to avoid sitting next to female strangers.

When to visit Iran

Visits to the south coast of Iran (eg: Bandar-e Abbas) are best made in the winter months of December, January and February when humidity and heat levels are at their lowest, while spring (March to mid-May) and autumn (mid-September and October) are the best times to travel around central and northern Iran. The summer months of June through to early September are best avoided as the temperature can be in the high 40s (˚C), although it is a dry heat except on the south coast.

Take the numerous public holidays into account if your visit is connected with business and/or your time is limited. Try to avoid Ramadan, the first ten days of Moharram (the sacred month) and the first week of the Nou Rouz celebrations, when staffing in offices and government departments will be minimal and all forms of long-distance transport and hotels will be extremely busy and expensive. However, during the Nou Rouz and throughout the high-season summer months, most historical sites and buildings have extended opening hours (until 20.00).

Climate

It is difficult to convey the reality of a land mass of 1,650,000km2, but Iran, with its 31 provinces, is three times the size of France, or the size of the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Italy and Switzerland combined. The Zagros Mountains in the west form a natural barrier with Iraq, and to the north are the Caucasian republics and those of central Asia, all of which were once within the territory of the former Soviet Union.

To the east are Afghanistan and Pakistan, while the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman mark Iran’s southern limits. It is a land of great contrasts, physically and climatically, as mountain ranges push up the mostly desert plateau of the centre. Apart from the green Zagros chain in the west, there are the snowy crags of the Alborz range in the north, the Makran Mountains in the south and the westernmost extension of the Hindu Kush, which force up the landscape of Iran’s eastern provinces.

This geological ‘upturned bowl’ effect means that towns on the same latitude but on either side of the same mountain range receive very different amounts of rainfall: Dezful (western Zagros, 143m altitude) gets approximately 358mm a year whereas Esfahan (eastern Zagros, 1,570m altitude) receives a mere 108mm.

Much less rain falls in the Great Desert basin, where some areas are pretty much unable to support any life at all. Generally speaking, regions south of latitude 34˚N get rain mainly during January, while those north of this receive most rainfall during the spring, especially April. An exception is the Caspian region, where the heaviest month for rain is October.

Few in the West are likely to associate snow with their mental image of Iran, yet about two-thirds of the Islamic Republic’s land mass usually endures heavy winter snowfalls (January–February) because of the average high altitude throughout the country. Tabriz (1,349m) in the northwest has about 30 days of snow a year, about ten days more than Arak (1,753m) to the east, whereas Esfahan, at a higher altitude, gets about seven days and Yazd (1,230m) about half this.

Of course, areas of very high altitude such as Mount Damavand (the so-called roof of Iran, 5,610m high) and especially its northeast face, Takht-e Soleyman in the Alborz range, and Sabalan (4,500m) near Ardabil in Iranian Azerbaijan have perennial snow as well as glaciers. Indeed, many Tehranis escape the smog and pressure of life within the overcrowded capital by flocking to the ski runs that drape the mountains, within a few hours’ drive of the city.

There are three if not four distinct climates in Iran: most regions have the continental climate of long, hot summers and short, sharp winters. In the northwest, the Iranian province of Azerbaijan shares a similar climate to that of Switzerland, and further east, along the south shore of the Caspian, it is as humid as the south, but without those gruesome higher temperatures. In the central desert region it is dry and insanely hot (NASA’s infrared satellites measured the Dasht-e Lut desert at Gandom Beryan cindering at 70.7°C during the summer of 2005). In August 2015, the town of Bandar Mahshahr in southern Iran recorded a ‘heat index’ of 74°C, the second highest ever recorded.

Events calendar

January

Join Iranians in their mid-winter festivities

Translated as ‘100 days’ before the Iranian New Year, jashn-e sadeh celebrates the most sacred symbol of Zoroastrianism, fire. Festivities include lighting fires outdoors, as well music and dancing. Main events usually take place inside Zoroastrian shrines.

February

Fajr International Film Festival

Celebrated since 1982 this festival is Iran’s largest cinema happening of the year featuring Iranian as well as international cinema. It is usually followed by the Fajr International Music Festival also held in Tehran with performances from Iran and abroad. February in particular is full of cultural and music events as part of the celebrations of the 1979 Islamic Revolution anniversary.

March

Dare yourself to jump over a bonfire

On the last Tuesday of the Iranian calendar, this fire-jumping festival is held as a prelude to Iranian New Year (Nou Rouz) celebrations on 21 March, marking the arrival of spring and awakening of nature.

April

Spread your picnic blanket to celebrate sizdah bedar

On 13th day of the Iranian month of Farvardin, in the much loved Iranian tradition of sizdah bedar, families gather outdoors to enjoy spring, good food and nature.

June

Spot celebs along the red carpet for Hafez

In the honour of the excellent Iranian cinema tradition, the best films and actors are nominated and awarded this prestigious prize for their work.

July

Join Iranians in their fasting during the holy month of Ramadan

The holy Muslim month of Ramadan starts in July and lasts into August. Throughout its duration Iranians refrain from drinking, smoking or eating during the daylight hours to teach themselves self-discipline, self-restraint and generosity. Share an evening iftar meal in this atmosphere of love and friendliness.

October

Drop in to a Zoroastrian shrine for the autumn mehregan festival

Devoted to Zoroastrian goddess of light, Mithra, the festival celebrates light over darkness. It is believed that Romans adopted Mithra worship from Iran and become devoted followers of the goddess.

November

Observe a religious Moharram procession

From late October into November (depending on the Muslim calendar), Moharram is considered to be the most important Shi’a ceremony. Marking the death of Imam Hossein, the central point of the holiest month of the year are mourning rituals. Mourning processions are held across Iran to express passion and the notion of martyrdom, a characteristic feature of Shi’a Islam.

December

Leave the dark nights behind with the winter solstice

Also known as shab-e chelleh, this celebration, usually held on 21 December, marks the first of the 40 days before jashn-e sadeh. Of Babylonian origin, the winter solstice celebration dates back to pre-Zoroastrian times and has to date remained an important feature of Iranian cultural tradition.

What to see and do in Iran

A spice seller at the bazaar © Mohammad Jhiantash, Wikimedia Commons

Esfahan bazaar

Since 1998 many more shops, including one or two selling the famous Esfahani gaz or nougat, have reopened in the covered arcade running all around the square. Before walking through the main 17th-century door of the bazaar, look up and you’ll see a Sagittarius figure and Shah Abbas victorious over the Uzbek enemy, as described by Jean Chardin in the late 17th century. The recent cleaning has also revealed a depiction of Europeans playing chess high up on the right. Above, there was a gallery where musicians banged and trumpeted every sunset, causing foreign merchants to suffer violent headaches, and a Portuguese bronze bell marking the Safavid conquest of Hormuz.

Just inside the door, immediately on the right, a narrow alley leads into a small courtyard of cotton block-printing workshops. There is an endless variety of printed cottons; prices depend on size, quality of the fabric and the colour complexity of the design. Dealers now greatly outnumber the makers and just one or two of them are retained to show tourists the basic technique.

The bazaar runs northwards and eastwards intermittently. The main carpet quarter is situated to the far left (west) away from the main street; a short walk through here will raise serious doubts in your mind whether there are enough homes worldwide to house all these carpets.

Fortresses of the Ismaili Assassins

As the Fatimid regime of Egypt and Syria began to crack and fragment in the 1060s, the Ismaili community in Iran began to dig in, securing strongholds to defend their villages and land. This valley of the river Alamut soon gained an international reputation as the ‘Valley of the Assassins’, with its chain of impregnable fortresses dominating the trade routes, and its team of highly trained men willing to sacrifi ce their own lives to safeguard the leaders of the Ismaili community, such as Hassan al-Sabbah in Iran and Rashid al-Din Sinan in Syria (the ‘Old Man of the Mountains’ as described by the Crusader chronicler, Joinville).

These were the young men whose clandestine activities spread terror among the Crusaders and Muslim military leaders as they infi ltrated inner court circles to ‘remove’ those who threatened their own community – leaders like the Seljuk sultan and champion of Sunni Islam, Malik Shah (r1072–92), his vizier Nizam al-Molk (assassinated 1092) and Richard Coeur de Lion.

As recorded by Marco Polo, rumours spread that Hassan al-Sabbah could instil such loyalty and single-mindedness only by drugging his followers with hashish (who were then known as hashashiyya, from which comes ‘assassin’) and promising them the delights of paradise.

The reality was that this was a tight-knit community with a rigid hierarchy under a charismatic leader – Hassan al-Sabbah – renowned for his scholarship and library. His death in 1124 resulted in serious disquiet within the community, and without the protection of the strongholds such as Alamut, perhaps its very survival would have been threatened.

Later successors followed more pragmatic policies, establishing links with neighbouring political powers, but the Mongol invasions changed all this. Circumstances allowed Hulagu, the Mongol commander, to seize and imprison the leader of the Iranian Ismaili community in Qazvin in 1256, heralding a massacre in which the fortresses were surrendered.

The community scattered throughout Iran but in the 1770s it was in control of Kerman and Bam, with the blessing of the Zand family. The leader of the Ismailis was honoured with the title of Agha Khan by Fath Ali Shah, but by 1840 the religious atmosphere had so changed that most of the community left for India and the rest scattered around central Asia, Pakistan and East Africa.

Hamadan

The Tomb of Avicenna

This 10th-century Muslim scientist, who originated from Bukhara, central Asia, was mentioned in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales but the monument itself dates from 1952 and was clearly inspired by the early 11th-century Gonbad-e Qabus monument in northeastern Iran. The museum on the ground floor was once dull and uninformative, but it has been been completely reorganised and is now a delight.

Local artefacts are located in the first room to the left on entry, while the room to the right is a library with interesting displays of historical medical instruments, such as the glass bloodletting suction ‘cuppers’ and manuscripts, while the main hall with the memorial to Avicenna shows the herbs, plants and seeds (with their Latin names) used in pharmacy with labelling in English and Farsi.

There is a good view of Mount Alvand from outside the upper platform, and the gardens are pleasant, although one dices with death crossing to and from the roundabout. Avicenna (born c980ce) fled from his enemies at court in Bukhara (Uzbekistan), arriving in Hamadan in about 1015 to practise as a doctor for some nine years. He then moved to Rayy and Esfahan, returning to Hamadan only to die of colic in 1037.

Most of his 130 or so books have been lost but fragments remain to show he wrote knowledgeably on economics, poetry, philosophy (influencing St Thomas Aquinas) and music as well as physics, mathematics and astronomy. His Book of Healing and Canon of Medicine became the standard medical textbooks in Europe until the mid 17th century; it is from Avicenna and other Muslim scientists that we get such words as algebra, alchemy, alcohol and alkaline.

Gonbad-e Alavian

Gonbad-e Alavian is a glorious if dusty tomb building; the girls’ school formerly here has been relocated. It is thought this was the mausoleum for members of the Alavian family, who controlled Hamadan for two centuries, but when it was built exactly is unclear.

To some scholars its elaborately carved plaster of leaf and flower motifs resembles Seljuk decoration as found at Divrigi and elsewhere in Turkey – as well as on the 1148 mausoleum Gonbad-e Surkh in Maragheh – but others argue the almost threedimensional, lace-like ‘Baroque’ quality of its motifs is early 14th-century Ilkhanid work.

The original roof has gone and much of the brick and plaster strapwork exterior has been restored but don’t be put off by the present monochrome colour, dust and gloom; let the plasterwork speak to you. The Quranic inscriptions inside (Q53:1–35), on the mihrab (Q36:1–9), outside (Q76:1–9) and over the entrance (Q5:55–6) refer to rewards and punishments, death and paradise, the importance of prayer and charity giving – all very apposite for a mausoleum and possibly the plaster leaf and plant forms symbolise the gardens of paradise. A torch is useful for the interior.

Nushijan Tappeh

Going 60km in a southerly direction from Hamadan towards Malayer, you arrive at Nushijan Tappeh. British archaeologists worked on this small Median site, about one-sixth the size of the main apadana platform at Persepolis, from 1967 to 1974. Four principal buildings were found on this outcrop: two temples, a fort and a columned hall with an enclosing wall.

The central temple, probably constructed before 700bce, had a narrow entrance leading into an antechamber possessing a stepped ‘Maltese cross’ groundplan and a spiral ramp to an upper level. It then led to a sanctuary with a triangular cella, or inner body of the temple and large blind windows with ‘toothed’ lintels decorating the walls. A brick fire altar (85cm high) with four steps was screened from the entrance and, perhaps to protect its sanctity from later squatters, the temple was filled with shale to a depth of 6m and carefully bricked in. This was a tremendously important find: perhaps the earliest temple with a fire altar in situ found in western Iran.

The second temple, located just to the west, had similar rooms and a spiral ramp but with a different orientation and an asymmetrical groundplan. The fort measured 25m x 22m, approximately the size of the Gate of All Nations at Persepolis, with four long magazines and a guardroom with another spiral ramp for access to at least one other floor, while the hall with a slightly irregular groundplan was somewhat smaller with 12 columns supporting a flat roof. Very little stone was used in construction throughout the site but the bricks (especially in the vaults) were often carefully shaped.

For some reason the site was then left largely unoccupied until the Parthian period (c1st century ce). At present the original structure is protected by an aesthetically unappealing steel roof, which regrettably spoils the authentic beauty of the site

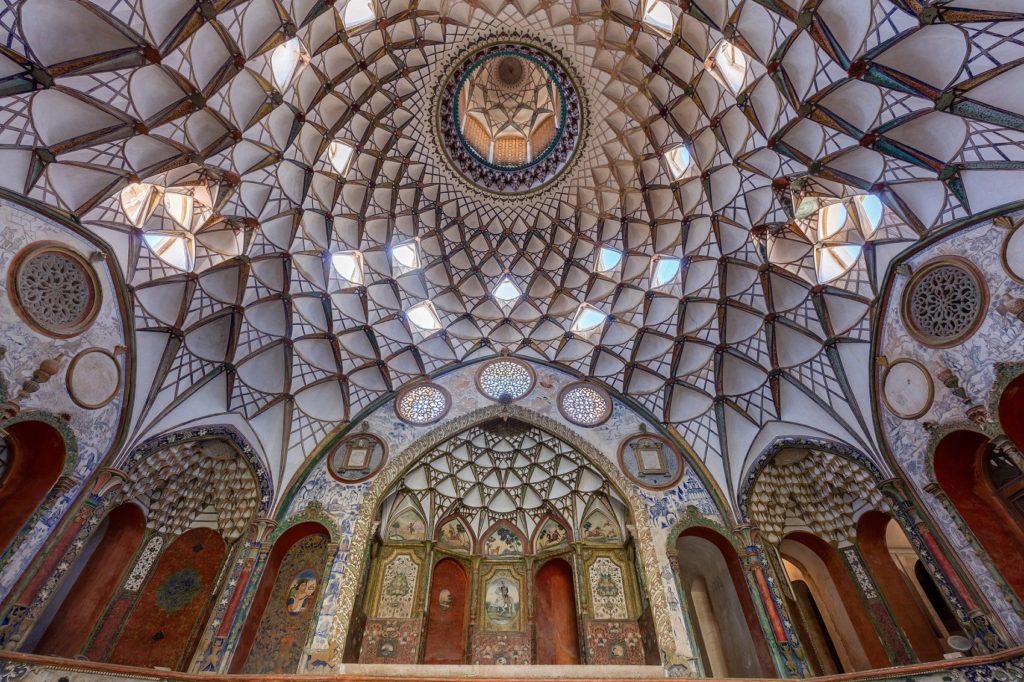

Kashan

Kashan will always be associated in Islamic art for its high-quality ceramics (kashi) production, which dates from the 12th century, even enduring the Mongol campaigns. It is also renowned for its manufacture of costly silks and carpets for the Safavid court.

The 17th-century English merchant, Thomas Herbert, estimated there were then approximately 4,000 families in the town mainly involved in textiles, which would mean that the community was then ‘in compass not less than York or Norwich … The houses are fairly built, many of which are pargeted and painted; the mosques and hamams are in their cupolas curiously ceruleated with a feigned turquoise.’

Undoubtedly he would also have heard that Kashan was the place from which the Three Wise Men set out for Bethlehem. Almost 250 years later, other English travellers reported that Kashan boasted 24 caravanserais, 35 hotels for foreign merchants, 34 hamams, 18 large mosques, and 90 small shrines but in such a bad state that Lord Curzon commented, ‘A more funereal place I had not yet seen.’ Matters were made no better by its reputation for poisonous scorpions.

Kashan’s most recent political history has been primarily associated with the nuclear installation in Natanz, 89km southeast from the city. The details of the facility for enriching uranium were leaked in 2002 and subsequently confirmed by President Khatami’s administration.

While the carpet industry here is one of the best in the country, the lack of shops selling them makes it next to impossible to find a good carpet. It is the old merchant houses, however, that make this city special.

Persepolis

More than any other ancient site in Iran, Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid in Persian) embodies all the glory – and the demise – of the Persian Empire. It was here that the Achaemenid kings received their subjects, celebrated the new year and ran their empire before Alexander the Great burnt the whole thing to the ground as he conquered the world.

It was Darius the Great who began construction around 515BCE, with his successors adding buildings, but it was still unfinished when, in early 330BCE, Alexander the Great burnt it to the ground after looting the city, seven years before his death. It took him, according to Plutarch, 10,000 mules and 5,000 camels to carry away the booty from this revenge attack for the Achaemenid firing of Athens.

The stone came from nearby quarries but the labourers came from all over the Achaemenid Empire including Greece, as the marks of the Greek toothed chisel testifies. Gold and silver foundation tablets (now in Tehran’s National Museum) were found on the site but more fascinating, for their wealth of detailed information, were the 30,000-odd clay tablets that were uncovered.

The complex consisted of military quarters, treasury stores, small private rooms and huge reception areas, but the exact function of the complex remains an intriguing mystery. Susa was the Achaemenid winter capital and Hamadan the summer residence, while Pasagarda was perhaps built to commemorate Cyrus the Great’s victory over the Medians. But Persepolis?

On the evidence of low reliefs showing visitors bearing gifts, and lions attacking bulls (Leo ascendant over Taurus suggesting spring pushing winter away), many assume Persepolis was used once a year to celebrate Nou Rouz, the spring equinox.

Frequent use of the lotus flower motif with its 12 leaves possibly symbolises the 12 months of the year and the always-green cypress tree could also be interpreted to refer to Nou Rouz, but such festivities are not mentioned in Achaemenid and later sources.

There seem to have been only two occasions when the Achaemenid ruler received gifts: on the official imperial birthday, and the annual sacrifice to Mithra.

The bull may also be depicted to represent a cow, a symbol of fertility and a guardian of nomad people.

Shiraz

Shiraz, with its long and rich history, friendliness and the laid-back attitude of its inhabitants, is one of the nicest and most welcoming cities in Iran. As the Iranian saying goes, ‘Esfahan for the head, but Shiraz for the heart’.

Despite dramatic growth in the last two decades to a population of around 1.5 million and the resultant traffic nightmare, Shiraz has miraculously managed to preserve the relaxed atmosphere of a provincial town, despite the daily assault on both its infrastructure and the nerves of its inhabitants.

It has an excellent university, which annually floods the city with an appealing wave of young, educated and friendly Iranians, who provide the real energy driving this fine city. Many foreign visitors are surprised that Shiraz itself has so few surviving historical monuments when there are such archaeological treasures in the neighbouring countryside, but earthquakes over the centuries have taken a heavy toll, along with the less excusable ‘urban development plans’ of the Pahlavis (for whom Shiraz was an unfortunate target of their dubious vision and largesse).

Shiraz is a place to stroll in fine gardens, see the Azadi Park Ferris wheel and roundabouts crowded with excited schoolgirls, chadors flying in the breeze. Both in the bazaar and in the major shrine, Shah Cheragh, you may glimpse the darker complexions of men and women from various tribal clans such as the Qashqai, the Qash Kuli and the Khamseh, visiting the city for provisions, clothing and jewellery.

Older men often wear a beige, hemispherical felt cap with a tall upturned rim, while women cover their immense skirts and glittering lurex tabards with black chadors; both caps and skirts are made in the bazaar. Many of these families still retain a migratory lifestyle, travelling with goats and sheep from Hamadan to Shiraz and the south in late autumn, returning in the spring, but some are now at least partially settled in outlying villages.

If you wish to see the rugs and carpets associated with such clans, the Shiraz bazaar is a good place to look, but prices are no longer low and quality is variable since such work was highly acclaimed in the West during the 1976 World of Islam exhibitions in the UK.

Tehran

Looking at the sprawl of modern Tehran spreading up into the Alborz foothills, it is difficult to believe that before 1795, when it became the Qajar capital, it was an insignificant village ‘possess[ing] nothing, not even a single building, worthy of notice’ (Thomas Herbert, 1627). Then, there were unimpeded views of Mount Damavand and the Alborz. As of the 2011 census the population of Tehran is over 12 million, which is approximately one-sixth of the country’s total figure.

While population growth in Iran from 2006 until 2011 has only been around 1.3%, the general urbanisation rate has now passed 70%, which may suggest further growth of the capital as more people from the villages are moving here in search of employment. Currently Tehran accounts for more than half of the country’s economic activity and is set to grow further. The inner areas of the city are home to around 50 colleges and universities, making it the most dynamic student city in the country.

Many tourists shun Tehran and proceed directly to the historical south, but the Iranian capital is a wonderfully diverse and vast city with a vibrant café culture and pleasant parks scattered around the city perimeter.

If visiting Tehran before and around Nou Rouz, you will be pleasantly surprised by light traffic, fresh air and flower blossom aromas at the city’s largest Mahallati flower market, selling more than five million flowers every day. While its southern parts (around Golestan Palace) offer, or rather conceal from the general view, a vast range of historic monuments, the upper affluent northern Tehran (Alborz foothills) is the place for an evening stroll or weekend mountain hiking (Tochal).

It is easier to get around if you think of Tehran, as one never-ending Vali Asr Street and everything else springing from it, like branches from a tree.

Yazd

The town has long been associated with Zoroastrianism, and the production of textiles. It fell to the Arab invaders in 642ce but the Zoroastrian community was strong here until the late 17th century. There were still plenty of adherents left in the 19th century, when official persecution caused many to flee to India or to Tehran, where the presence of foreign diplomatic missions offered more protection.

Today, Zoroastrians form less than 10% of the town’s population, mainly located in the Posht-e Khan Ali quarter. When Marco Polo visited in 1272, noting its fine textiles and its strategic location on trade routes from India and central Asia, this ‘Good and Noble city’ was walled, but undoubtedly today he would get hopelessly lost in the confusion of ring roads and roundabouts.

Today Yazd is one of the most tourist-friendly cities in Iran, and offers excellent souvenir-shopping opportunities. Look through the workshops selling handwoven silk cloth termeh, produced solely in Yazd. Traditional hotels are abundant and conveniently located in the old town centre, while many tourists and backpackers use the City as their base to explore nearby desert dunes. Yazd is also known as the hosseiniyeh of Iran, the centre of the Imam Hossein commemorative celebrations in the country.

Although it does not possess any royal monuments like those at Persepolis, Shiraz and Esfahan, Yazd is renowned for its vernacular buildings, including ice houses, water cisterns (ab anbars), domestic houses and spectacular wind towers (badgirs) – of which Yazd boasts one of the tallest in the world.

Two dakhmeh (Zoroastrian ‘towers of silence’) are situated a little south of town. In accordance with Zoroastrian laws governing the sanctity of earth, fire, air and water, in Achaemenid times the dead were exposed and their bones later gathered to be placed in ossuaries or tombs in rock.

But in later centuries large circular stone walls were built on rock and the bodies of Zoroastrian men, women and children were placed on their designated, paved zone on the open stone platform inside. Sadly, the local authorities have turned a blind eye to vandalism of these buildings, which only serves to fuel foreigners’ negative perceptions of religious tolerance in modern Iran.

Related books

For more information, see our guide to Iran:

Related articles

From crumbling Persian empires to colossal Roman cities, here are some of our favourite ruined civilisations from around the world.

Discover our favourite sights along one of the most important trading routes in history.

Sit back and enjoy this kaleidoscope of colours.

Marble caves, salt lakes and rainbow mountains.

Discover Iran’s greatest evidence of Elamite civilisation, dating back 3,500 years.