There’s something undeniably enticing about caves. Dark, mysterious and otherworldly, exploring underground worlds can feel like stepping into a whole new dimension. From Greece to Georgia and everywhere in between, here’s our pick of the best.

Cave Hotel, North Wales

A four-star cave? Surely not. But that’s exactly what you’ll discover near the foot of a peak called Cnicht in North Wales. OK, so maybe the star rating isn’t exactly official, and perhaps the beds are a little harder than you might hope and the bathroom more… al fresco. But still, if stars were awarded for location alone, the night’s accommodation that awaits you on this escapade would easily merit a confident five.

Tucked in between the boulders above an unnamed lake is a collection of rocks that make up a stone hotel – or, to be more accurate, a cosy chamber that comfortably accommodates one or two people. Rugged it may be, but the view over towards what some call the Matterhorn of Wales more than makes up for it.

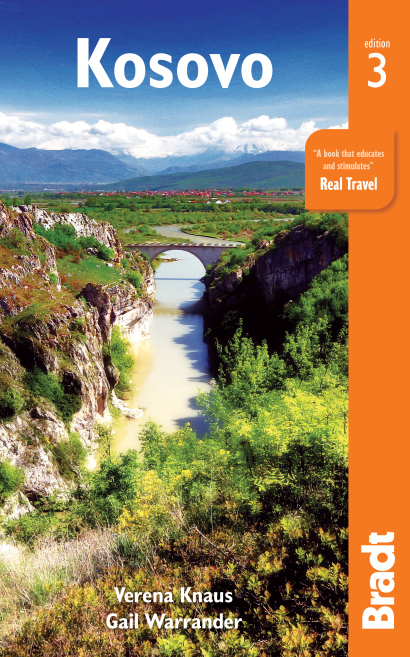

Caves of Gadimë, Kosovo

This large, karst limestone cave with dozens of stalactites and stalagmites of differing colours is found in the village of Gadimë which has a mixed population of Ashkali, Roma and Albanians.

It was discovered in 1969 by Ahmet Diti when doing work on his house nearby and was opened to the public in 1976 after exploration by Yugoslav speleologists. The cave is 1,200–1,500m long, with a 500m section open to tourists.

Caves Road, Western Australia

Margaret River is home to at least 350 caves, a few of which have been safely opened up to visitors. Heading south on Caves Road, the first show cave you come to is the 300m-long Calgardup Cave, with boardwalk and stairs suitable for children. Its chambers are a stream of colour and from winter to spring, water flows through the cave, creating an amazing reflection effect. Just 1km south is Mammoth Cave, which has been open to visitors for more than a century.

Another 3km further along Caves Road, Lake Cave has a rather dramatic entrance – down 300 or so steps, past giant karris – and inside is an internal cave lake that is crossed by a footpath. The showstopper is the ‘Suspended Table’ – a huge, 10m² piece of calcite. The final cave along this stretch is also the deepest in the national park – Giants Cave, with a depth of 86m. There is about 500m of chamber to explore; however, negotiating this cave requires navigating vertical ladders and rock scrambles, and children under six are not permitted.

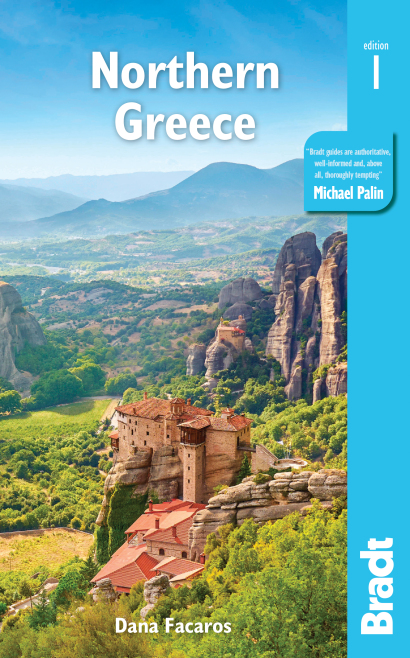

Diros Caves, Greece

The Diros cave system is one of the finest in the world, with its magical combination of stone and water. Whilst they can be crowded, it is worth persevering, as the caves are truly stunning, with countless stalactites reflected in crystal clear pools of water.

The tours take place on small punts, which each take about ten adults and are guided through the warren of tunnels and chambers by skilled, but usually unresponsive, ferrymen.

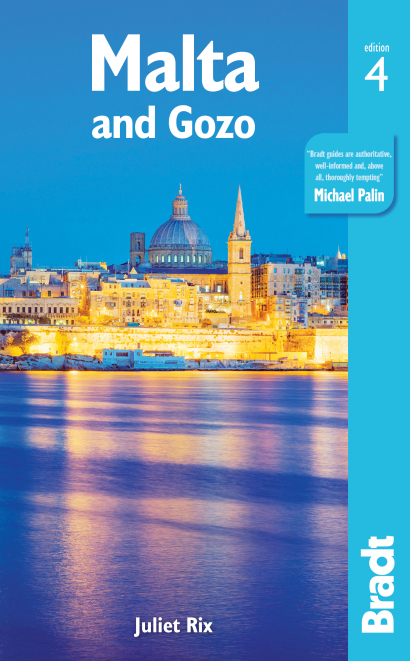

Għar Dalam, Malta

This natural cave (pronounced Ar Dalam and meaning the ‘Cave of Darkness’) was one of the first places in Malta to be inhabited by humans who arrived on the islands in the 6th millennium BC. The presence of these early people is known from human remains, animal bones in rubbish pits and pottery.

The pots have simple geometric decoration made by etching into the wet clay and are of the same style seen in Sicily during this era, suggesting that the first Maltese came from the neighbouring island 93km away.

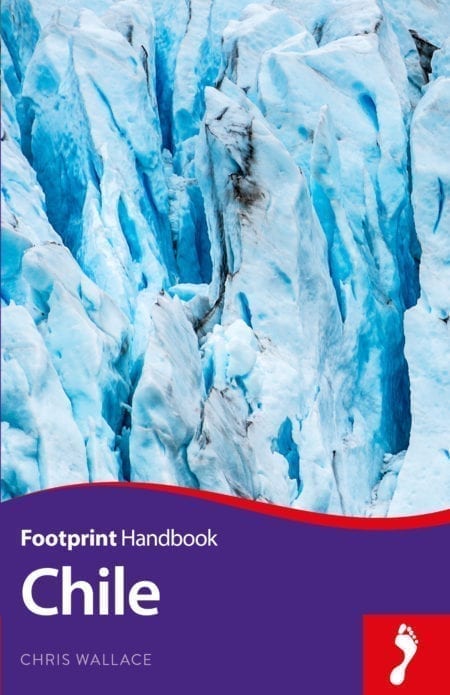

Marble Caves, Chile

The glacial waters of Lago General Carrera have eroded the limestone walls surrounding this section of the lake over centuries to form unusual, Salvador Dali-esque caves. These structures appear almost to have melted into the water, supported by frozen-in-time lava-like columns which disappear into the watery base of the caves.

Some of the caves are large enough for small boats to sail into them and, on a sunny day, the light reflects off the cave walls and from the relatively shallow pools at the bottom of the caves creating surreal ripple-like patterns along the walls while the water itself reflects in myriad shades of turquoise.

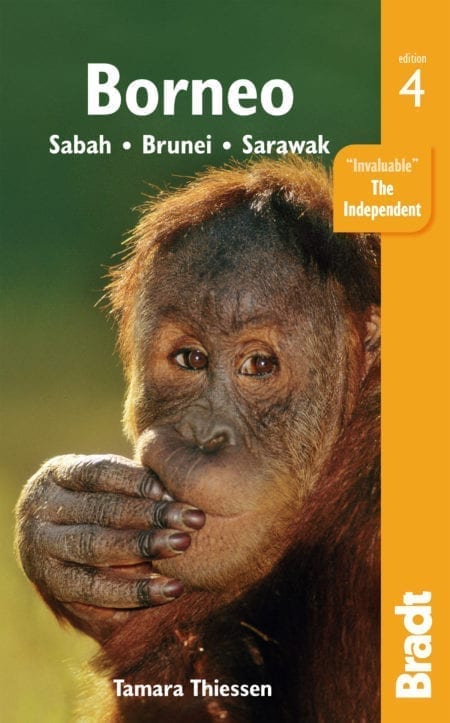

Niah Caves, Borneo

The Great Cave of Niah is enormous by any measure. The floor area of the cave has been calculated at almost 10ha, and in places, the majestic cave roof rises 75m above the rubble-strewn floor. As well as being home to multitudes of bats, darting swiftlets (their nests are the famous ingredient of Chinese bird’s nest soup) and the occasional snake, it is also the site of human occupation dating back at least 46,000 years.

The richness of the deposits at Niah, and the great span of time they encompass, marks the site as one of the most important archaeological sites in Southeast Asia.

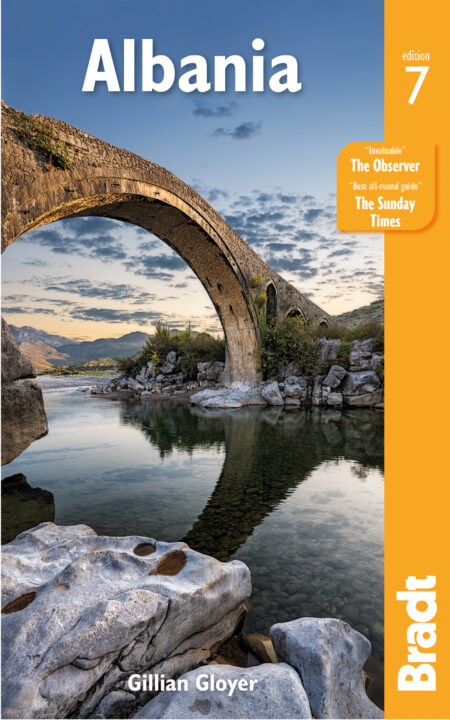

Pëllumbasi Cave, Albania

The hike up to Pëllumbasi Cave makes for a very pleasant day out if the weather is good. Also known as the Black Cave, it was home to humans at various points between the Stone Age and the early Middle Ages, and to cave bears a long time before that. (Cave bears became extinct about 27,500 years ago.)

The cave is 360m long and has chambers filled with wonderful stalagmites and stalactites. There are also, as one would expect, many bats.

Scărişoara Ice Cave, Romania

Situated right up in the northwest corner of Alba County, deep in the Apuseni mountain forests, the Scărişoara Ice Cave (Peştera gheţarul) is the biggest ice cave in Romania and a unique phenomenon in southeast Europe. The exact date when the cave was discovered is unknown, but the German geographer Adolf Schmidl mentioned the cave in 1863 and made the first map. Scientists believe that the cave was created during the Ice Age, when the mountains were covered with ice and snow.

Scărişoara is a truly impressive sight as visitors enter the underground glacier at a height of 1,165m through a large sinkhole and walk on 70,000m³ of 23m-thick ice, descending 48m to two chambers at the bottom of a great abyss. The most stunning ice structures are found in the second chamber, ‘The Church’, where the pillar formations reach more than 3m high and stalactites and stalagmites shimmer eerily all around.

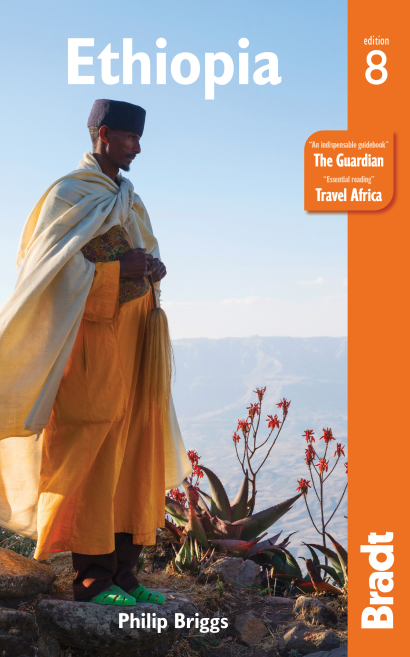

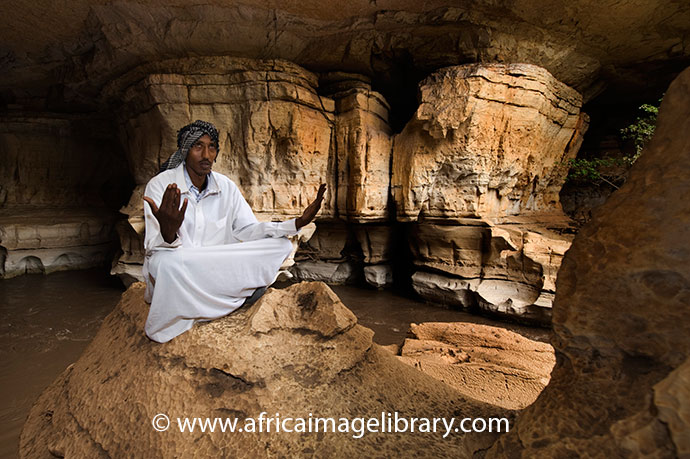

Sof Omar Caves, Ethiopia

This vast network of limestone caverns, reputedly the largest in Africa, lies at an elevation of 1,300m in the medium-altitude plains east of Robe. It has been carved by the Web River, which descends from the Bale Highlands to the flat, arid plains that stretch towards the Somali border.

Following the course of the clear aquamarine Web River underground for some 16km, the caves are reached through a vast portal which leads into the Chamber of Columns, a cathedral-like hall studded with limestone pillars that stand up to 20m high. The caves are named after Sheikh Sof Omar, a 12th-century Muslim leader who used them as a refuge, and they remain an important site of pilgrimage for Ethiopian Muslims. Their religious significance can, however, be dated back further to the earliest animist religions of the area.

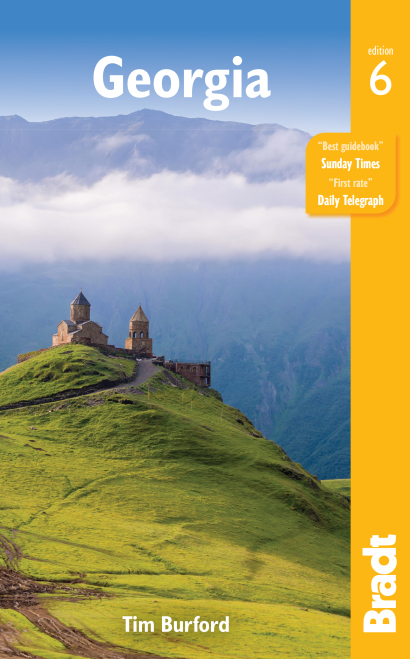

Vardzia, Georgia

This is one of Georgia’s most impressive sights, and it’s most famous cave-city, largely because of its connections with Queen Tamar, and is a place of almost mystic importance for most Georgians. Having been in a closed border zone throughout the Soviet period, it’s now receiving plenty of visitors, at least in summer.

It’s said that its name derives from ‘Ak var, dzia’ or ‘Here I am, uncle’ – Tamar’s call when lost in the caves.

More information

For more information, check out our guides: