The upstairs gallery holds the museum’s most unexpected displays – frescoes from Christian Nubia. Despite lasting for 700 years, Sudan’s early Christian kingdoms are little known to the outside world.

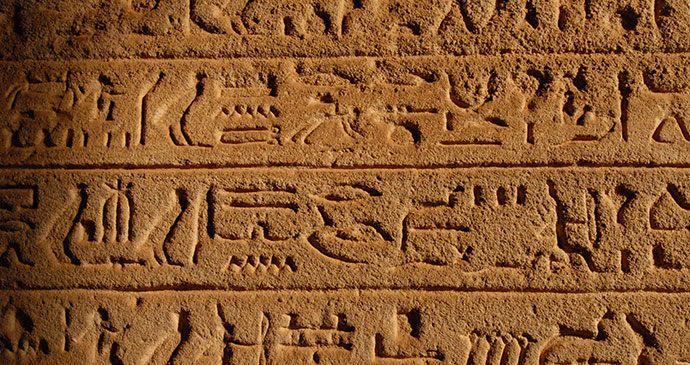

The National Museum holds many treasures of Sudan’s ancient and medieval past. They’re well presented and labelled, and give a good narrative of Sudanese history. Spread out over two floors, the ground floor starts with Sudan’s prehistory and covers the rise of Kerma and Kush in great detail. Kerma is particularly well represented through its famous pottery. The Kushite displays show the wide variety of cultural exchange in play throughout the kingdom. Egyptian culture is the strongest influence, shown particularly in the royal statues found at Jebel Barkal dating from around 690BC and the sarcophagus of Anlamani from his tomb at Nuri about 100 years earlier. A clear Hellenistic influence can be seen in the statue of the so-called ‘Venus of Meroë’ and a blue-glass chalice from Sedeinga, with depictions of gods and bearing a Greek inscription ‘You shall live’. A side room on the ground floor has space for temporary displays, often illustrating current archaeological digs.

The upstairs gallery holds the museum’s most unexpected displays – frescoes from Christian Nubia. Despite lasting for 700 years, Sudan’s early Christian kingdoms are little known to the outside world and repeated Sudanese governments have shown little interest in promoting this aspect of their history. I was as ignorant as most on my first visit, and was astounded to find beautiful frescoes depicting Christ and the Virgin Mary, along with a host of archangels, saints and apostles. The style of the frescoes is distinctly Byzantine, reflecting Nubia’s links with the Roman Empire in the east. Most were painted between the 8th and 14th centuries, and were taken from the cathedral at Faras, now submerged under Lake Nasser. The upstairs galleries can be a little dark, so you may want to take a torch with you in order to see the details in the frescoes.

Underneath purpose-built structures in the museum’s grounds are three remarkable temples rescued from the flood waters of Lake Nasser in the 1960s and resurrected here. The Temple of Kumma dates from 1473–1400BC during the reigns of Queen Hatshepsut and the pharaohs Tuthmosis III and Amenophis II. It was part of a series of fortresses built during the Middle Kingdom period to control the movement of goods and troops up and down the Nile. This particular temple was located at the Semna Cataract approximately 60km south of Wadi Halfa, which was then the frontier of Egyptian control. Part of the much larger Kumma Fortress, whose outer walls reached 10m high and 5m thick, the temple was situated in the northwest corner of the settlement and originally surrounded by mud-brick houses and storerooms connected with the everyday life of the priests and the worshippers.

Roughly contemporary with the Temple of Kumma is the Buhen Temple, dedicated to the falcon god Horus. What you see here is an inner temple divided into five rectangular rooms that would, in ancient times, have been surrounded by an outer courtyard with mud-brick walls. When Tuthmosis III came to power around 1450BC he systematically removed the names and depictions of earlier rulers and substituted them with his own. He also enlarged the complex significantly and placed within it stele proclaiming his victories in Libya and Syria. Later rulers altered the entrance way and widened the doors. The temple remained in use as late as AD450, after which time it was partially incorporated into a church.

The third temple is the Temple of Semna, built by the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom as part of the fortifications at the Second Cataract, 60km south of Wadi Halfa. The temple was dedicated to the Nubian god Dedwen and the main building was constructed from stone, surrounded by a mud-brick wall. Projecting columns known as pilasters decorated the central courtyard and the reliefs, a later addition to the structure, depict Tuthmosis III. The temple remained in use at least until the 7th century BC. If you are interested in Sudan’s archaeology, the museum hosts regular archaeological conferences and seminars that are open to the public. Ask at reception for details.